Aric Verrastro

Aric Verrastro

“You take the home from the boy, but not the boy from his home,” Jon Bon Jovi croons in “Who Says You Can’t Go Home.” And it’s true of Aric Verrastro. Growing up in Buffalo, New York, Verrastro didn’t always appreciate his hometown. He recalls visiting the Rust Belt city’s abandoned Central Terminal train station with his siblings and throwing rocks at the windows of the dilapidated building. It was only well after he left home, to pursue his MFA at Indiana University in Bloomington, that Verrastro became so inspired by his hometown that he dedicated his thesis project, Timekeepers, to the city.

A key moment came in 2014, in the midst of his study of metalsmithing, when he had finished a body of work and wasn’t sure what would come next. The artist, now 31, had gone home to visit family and friends, and heard about an urban renewal project at Silo City, a compound of abandoned grain silos on the Buffalo River being reimagined as an arts district. An evening event at the site, featuring art installations and light projections, left him feeling “intoxicated and inspired,” he recalls. Returning to IU, “I just knew that I had to make work about this.”

Researching Timekeepers immersed him in the city’s rich history. Buffalo’s heyday as an industrial center hit a peak in 1901, when it served as the site of a World’s Fair (best known today as the event where President William McKinley was fatally shot). The city continued with a building boom, fueled by continuing scientific and technological advances. As the decades passed, however, its mainstay steel and grain industries faltered, and the local economy declined along with them. Buffalo was the country’s eighth most populous city in 1900, but 1960 was the last time it ranked in the top 20. Today, it’s the third-poorest city in the US.

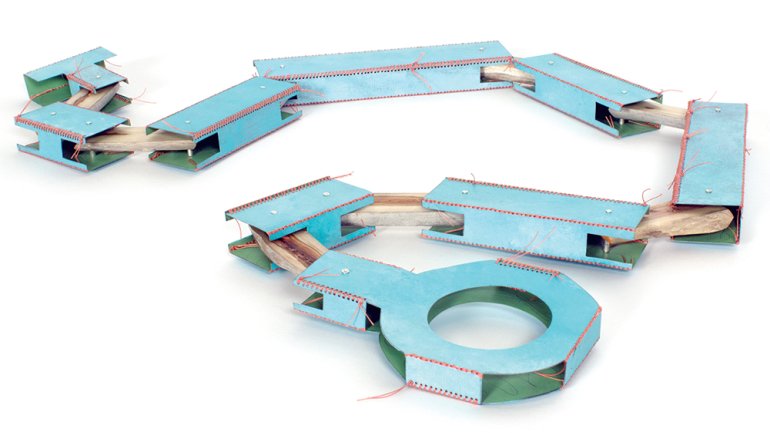

Still, the last few years have seen the beginnings of a turnaround, with job growth and investment; a number of the city’s once-deserted buildings are being refurbished. These signs of hope fueled the 19 wearable souvenirs of Buffalo that comprise Timekeepers.

“It would have been easy,” Verrastro concedes, “to make work about urban decay. Instead, I chose to focus on the positive renewal.” While making the pieces, he “became the foreman of my own miniature city,” he says, “and my bench was the construction site.” All of his materials, such as driftwood and steel, originate in Buffalo. His palette was inspired by the city’s colorful buildings and nickname, the “Rainbow City.” The artist also employed newer technologies, such as 3D printing, to produce some elements, paying tribute to the 1901 World Fair’s focus on innovation.

How did Verrastro visualize Buffalo as he made jewelry in Indiana? He asked his father, a photographer, to shoot pictures of the city for him. As he worked, his father’s photographs transported the artist back home.

His goal now is to publish a catalogue of Timekeepers, encompassing his jewelry as well as his father’s photographs. Verrastro also hopes that collectors of Timekeepers pieces wear them proudly and recount the story of Buffalo – as it was then and as it is now.

Bella Neyman is a gallery director, curator, and journalist in Brooklyn.