Artistic Risk and the Ticking Clock

Artistic Risk and the Ticking Clock

Throughout my career of more than 50 years, I’ve been more comfortable sitting in my studio than in my living room. From the start, I’ve felt pulled into the studio, drawn to learn from the process of crafting objects well.

And I’m proud of what I’ve learned. My professional accomplishments include retrospective exhibitions, work in more than 80 museums worldwide, three honorary degrees, and three books.

Yet I’m still battling the muse to “get it right.” You’d think that, at 74, I’d be more relaxed – and less obsessed with finding new ways to craft intricate botanical works. But it’s not that way. I’m no psychologist, but maybe my relentless drive has something to do with my early academic failures stemming from undiagnosed dyslexia. Or maybe I owe it to the years I spent wanting to please my father, who died more than four decades ago.

But this is who I am. And each day, when I enter the studio before dawn and switch on the lights, I’m keenly aware of the quiet space connecting to my psyche. Along the walls of the hot-glasswork area are benches laden with hand tools, annealing ovens, various glass failures, works in progress, and objects I’ve collected or been given. The place is my touchstone.

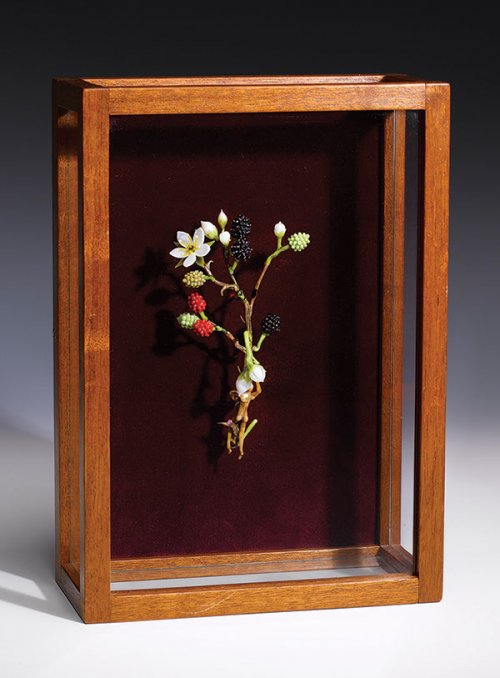

It was to this studio, in January, that an experimental, free-standing piece I made in the early 1990s came back for repair – a botanical model of a flowering blackberry plant with blossoms and berries suspended in a display case. Somehow, I felt challenged by this work and emotional about it; it became an unexpected inspiration. Sitting there, it reminded me of earlier times and childhood walks in the woods that connected me to the plant kingdom. I made this piece more than two decades ago, yet I’ve become intrigued by the possibilities it suggests. Once I repaired the damage, I’ve found myself sketching and imagining ambitious botanical iterations. I found myself feeling anxious to work on a wholly new concept – something apart from my life’s work.

I imagined referencing a native plant that has been pulled out of the earth, with leaves, a flower, soil, roots, insects, and dirt clinging to the root hairs. I wanted to pay homage to the mystery of unseen energy and the fecundity of nature. And I wanted the piece to be free-standing, not encapsulated in hot glass like the work I am known for, the signature work I’ve spent my life making. To protect the delicate glass plant, I knew I would have to try casting in resin, which I’ve never done. It felt like a serious challenge.

I was surprised by how much discomfort I felt starting out. As I sculpted the roots and solved some basic technical problems, the idea slowly took shape. But I was making forms I didn’t know – and didn’t know how to make. I felt uneasy.

I’ve told students endless times to take risks and have artistic courage. Yet there I was, suffering headaches from anxiety, fretting about my ability to capture the plant kingdom in glass. I felt my ego competing with the entire history of floral art, yet I knew I wanted to sculpt something very personal. I knew my craft skills could handle the project technically, but I really didn’t want the results to be sophomoric.

By the end of April, I had my first glass model of the sort of work I was envisioning. For me, it represents a new commitment to the future, with all of the uncertainty and zillions of technical issues that come with that. I titled the work Earth Clump.

Whatever becomes of it going forward, this innovation is enhancing my other work. When I’m sitting at the bench making components for my ongoing Orb series, the Clump-in-progress sits in my peripheral vision. Like a gift, the Clump elements are nurturing a reinvigorated focus on the orbs that has led to a more ambitious, nuanced root system, suggesting a poetic metaphor for life energy.

Still, I’m on an emotional roller-coaster. The high: At 74, I’m still growing as an artist. The lows: I’m worried about the fragility of the design and the cost of construction.I’m going against decades of focused refinement along a botanical centerline. I’m working at a larger scale after decades of working small. I’m trying a new material.

I keep asking myself: Do I really want to take on this new challenge, venture down a new path, not knowing how much time I have left? Can I deal with negative public scrutiny at this stage of the game?

I consider that last question, and the answer comes back yes.

The truth is, I’ve never felt satisfied with my work. Now, as I develop new illusions with fresh potential, I feel excited and upbeat. Whatever I’m working on, I value my craft as never before. Preparing materials, which I used to routinely delegate to an assistant, is now a wellspring of satisfaction. Tedium no longer exists; tasks I once considered ordinary I now savor. Alone in the studio, sitting at the bench behind a torch, I’m in the moment, enjoying the work for the sake of the work. I have a heightened sense of respect for skill as a spiritual experience. My artwork is an act of faith – like a prayer.

My commitment as a studio artist, fueled by visions of new things I might make, is as strong as ever. I have a work routine, shaped over decades, that I revised in 2015 to fit in prostate cancer treatments. (In a funny way, having cancer was a positive experience – it dictated a heightened sense of being and a more flexible work schedule.) Today, I take more time to “give back” through writing, teaching, and giving lectures. I do my signature work for the galleries that represent me. But I make sure I have ample time for experimentation.

I’m curious about my future. What’s ahead? I don’t know. But I do know that, in every sense that matters, my future is now.