The Big Picture

The Big Picture

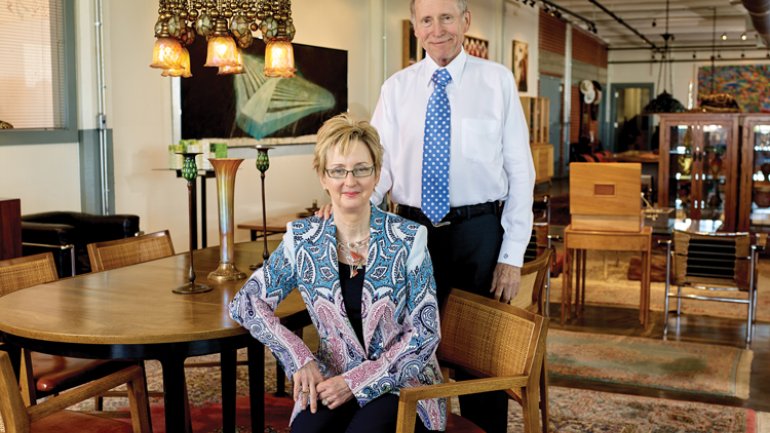

In Kansas City, Dick Belger and Evelyn Craft Belger are working to support the arts, across the country and in their own backyard.

Alongside a railroad track and across from a crane yard, the industrial buildings that Dick Belger and Evelyn Craft Belger call home don’t look like much from the outside – which makes what’s inside all the more astounding. Renovated between 2010 and 2013, the Belger Crane Yard Studios complex in Kansas City, Missouri, houses a 10,000-square foot gallery space and an array of arts initiatives, including the Lawrence Lithography Workshop, ceramics hotspot Red Star Studios, a metal workshop (Asheer Akram is the current artist in residence), and wholesale/retail supplier Crane Yard Clay.

A passionate collector, Dick moved into a loft here around 2005, the year he met Evelyn. (They married in 2009.) At the time, the only tenant was the Lawrence Lithography Workshop; three of the four buildings were vacant or being used as storage for the eponymous cartage company Dick’s grandfather founded in 1919, and which the couple today leads. At first, Evelyn says, the 6,500-square-foot loft was a space to pursue their shared interest in collecting midcentury furniture. But the couple has another drive in common: strengthening arts communities.

A mile away on Walnut Street, the Belger Arts Center occupies two of three floors in the cartage company headquarters; its free exhibitions often draw from the collection of the John and Maxine Belger Family Foundation, which collects the work of artists in depth (rather than acquiring only a few representative pieces). The goal is to provide a unique and loanable resource for scholars, curators, and the public. In addition to her role with the cartage company, Evelyn is executive director of all the arts initiatives, including the foundation and the center, Red Star Studios (which came under the Belger umbrella in 2010), and now the crane yard expansion; previously, she led the Morean Arts Center in St. Petersburg, Florida, for 12 years, shepherding it through its own dramatic expansion.

Some people might have hesitated to bring work home in such a literal sense. Not this couple. “I saw the buildings, and I thought, oh my gosh,” Evelyn recalls. “They’re out of the way. They’re not being used for anything. Art is perfect.”

What’s in your loft is a sliver of the collection, spanning midcentury furniture and Tiffany glass to paintings and ceramics. How do you decide what to live with and what to exhibit?

Dick: Well, basically, what we exhibit is what anybody wants. [The art center and foundation exist to develop touring exhibitions and to loan works.] So that’s user-driven. What we decide to live with is we just kind of pick a few things that we think are representative of what we do collect. Everybody always says, well, what’s your favorite thing? Well, there isn’t any. Good stuff is good stuff. How do you pick one?

I understand you have a very deliberate approach to collecting, however.

Dick: I’m a believer in process – I like to look at things, like an artist’s early work, and see where it goes, see why he or she does certain things. It’s real simple with decorative arts – more simple, I’d say – because you can definitely see that lineage going down the road: Well, why’d they do this? Well, they were having a problem so they did that, trying to correct this problem, which generated that problem. That’s what I like about collecting – you learn things. If you quit learning, you’re dead.

Collectors now, everybody wants to buy the masterpiece. I don’t. I want to buy the pieces that probably no one else wants, because they represent that process the artist is going through to get to that masterpiece.

Evelyn: Well, you also have some excellent pieces, too! You don’t buy just the duds.

Dick: I just buy junk. I’m a junk collector.

Evelyn [laughing]: No, you don’t. But you like to see the different things artists try along the way before it’s fully resolved.

Evelyn, you have a slightly different approach?

Evelyn: Yes. I see pieces that I love and mean something to me, and I think they’re really good – so I like to get them, to buy them.

Recently I’ve had much more of a ceramics focus, but together we’ve also bought a survey of work from Creighton Michael, who is a 2D and 3D artist, and we continue to buy William Christenberry and Terry Allen. And Don Reitz with ceramics – that one fit with the way Dick likes to do things; we assembled a survey, sort of, of his life.

Dick: It’s rare when you find an artist who has early work left. Fortunately, Don had some of that early work. I’d love to have the last piece that he ever did, but I’m not sure we’ll ever know what the last piece really was. But you know, we got real close on the first pieces.

Evelyn: We also make it a point, whenever we can, to buy work from student artists or young emerging artists. Some of it is not representative of where they will be one day in their career – or not; some of them stop, you know. But we call that the encouragement collection. There are quite a few pieces; we’ve got some really divine work from students.

Dick: It sends them a message: Hey, maybe I can make a living doing this. And that’s something they need.

You lived here since before it was the Crane Yard Studios. Has your life changed at all since all the artists moved in?

Evelyn: It really has not! We have an active studio right downstairs, and I guess we’re old and deaf, but we don’t hear them at all. It has made our lives richer, however, in that you can walk through at any time and see art in the making. It’s wonderful to have that, to be able to interact with people in creative thought, easily, at the drop of a hat.

The [staff] here – Tommy Frank and Michael Baxley, Brock DeBoer and Frank Craft – have done a great job in the selection process for residents and for the studio members. They’re all really interesting people, and they have a great sense of purpose and identity in what they’re doing. My only regret would be that I don’t have time to interact with them more.

That’s a great way to describe it: a sense of purpose and identity. That really comes across when you talk to the people here, that you’re building something, together – and it’s special.

Evelyn: It is special. I’ve never had anybody say anything other than “Sure!” or “That’s a great idea!” or “How can we do that?” My challenge has been – after that first year – to make sure that no one overdoes it, to ratchet us back, because everyone was saying yes to everything.

Is there anything here that would surprise people?

Dick: I think people are simply surprised by this type of interior in a warehouse building in this part of the city. They don’t expect anything like this.

Evelyn: There were concerns at first about the location being potentially dangerous – the studio hours, people keeping all hours, some of them young women. But that’s another reason for us to be sure to live here. It gives somebody here all the time. When we first lived here, before all this [was renovated], there was quite a bit of unsavory activity going on right at that dead end. In time, that has improved; it doesn’t take much.

We’re really close to the 18th and Vine area, the Jazz District, and they’re doing an excellent job of connecting [with the community]. And we’re working in other ways to connect. We do a lot of free children’s programming and we are trying to target that in our geographic community as much as possible.

You need to do what you can in a global way and in a local way and right in your own backyard. If you can figure out how to do a little bit of all of that, maybe some good will come of it.

That seems to be a cornerstone here, the idea of not just supporting artists by, say, buying work, but supporting the big picture. Why is that so important?

Dick: In the mid-’70s, I was on the board of the Kansas City Art Institute, and the thing that I remember is we’d sit up on the stage, and all of these young students would come by and pick up their degrees and walk out the door and go to the airport. And they’d go to the Right Coast or they’d go to the Left Coast. No one stayed here. And that’s because we didn’t have that viable arts support.

If you’re going to have a viable arts community, you need support. You need people who can restore art, you need people who can photograph art, you need printers, you need all those different people, not directly artists, who aid and assist them in a sense. And over time, with everybody pulling on the oar, that’s built up. And you don’t have that [exodus] now; a bunch of students that graduate here stay here. And that makes a city better.

Evelyn: There’s an incubator effect. That’s a word that’s bounced around way too much, but ideas feed off of each other, and energy oftentimes needs that critical mass. You see that in the ceramic studio [downstairs]. Some of the artists have studios at home, but they want to be part of a bigger environment, to keep their energy and their ideas and their creative edge going.

When I was living in St. Petersburg, the mayor asked me why I liked Kansas City so much. And I said, “Well, it’s because you’ve got so many different things.” It’s not just the institutions, which are wonderful, or the dance, which is wonderful. It’s all the unlikely things that bubble up. Some of them make it and some of them fail, but there’s this energy that is at all different levels – from the most accomplished to the most basic and beginning. And you need that dynamic to make a city grow and not become stagnant. And that creativity does spill over into the business community, into making a city something better. What’s the quote?

Dick: Civilizations are remembered for the arts, not their sewers.