Cabin Stories

Cabin Stories

Welcome to Slumgullion (The Venerate Outpost).

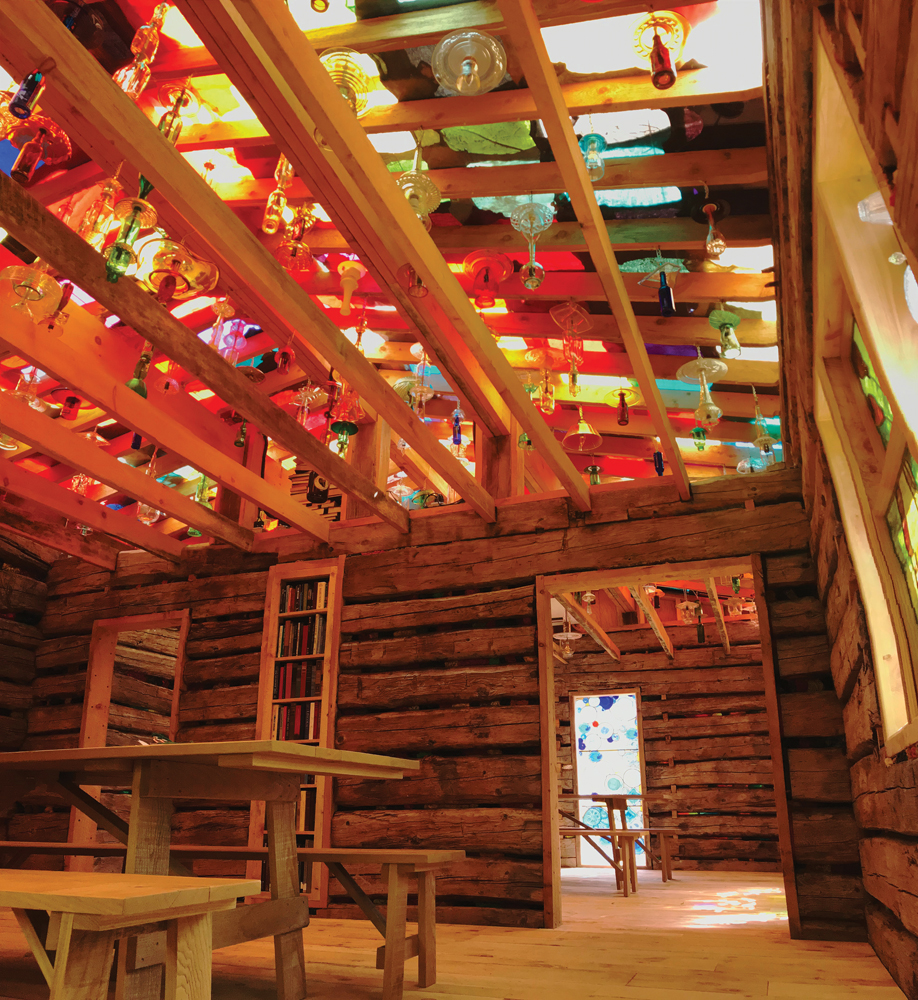

The cabin-turned-artwork by Minnesota stained-glass artist Karl Unnasch was commissioned by the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where it now stands.

Comprising a historical log home, reclaimed objects of daily life, and colorful stained glass, the permanent installation aims to inspire a sense of wonder. Through its materials and construction, which intentionally showcase the work that went into them, it’s also an ode to the hard labor that’s often a part of rural life.

Unnasch’s practice, which spans public and architectural art, is informed by his experience helping maintain his family’s 200-acre dairy farm in rural Minnesota. “I grew up building fences with my brothers and dad,” he says, before joking: “That wasn’t summer vacation. That was summer.”

Although “slumgullion” can mean many things, the artist is particularly drawn to it as a term for food made out of leftovers. “It shows how everything doesn’t need to be new; old stuff, if prepared right, can be made new again,” he says.

Here Unnasch narrates a few of the stories embedded in the materials from which he crafted Slumgullion. ~The Editors

Photo: Nicole Huss

I came across this cabin in 2005. I was on a fishing trip with my buddy, and we stopped by an antiques store on the side of a road in Wisconsin. The owner and I ended up speaking about old log cabins, and he mentioned that he had one with two rooms for sale, although it was disassembled. In my experience, finding a log cabin that’s just one room is easy. Finding one that’s two rooms is like finding a unicorn. So I paid cash for it and hauled the logs away with no blueprint for rebuilding it, outside of an old photo.

I was eventually able to track down the people who last occupied the cabin. They are now quite elderly. The husband had been living in it as a bachelor when he met his fiancée. After they married, they lived in it for a little bit. Then she says, “If we’re gonna stay married, we’ve got to have a ‘real house’ to live in.”

You’ll notice there’s a lot of stories ingrained into the logs by the people that owned and lived in the cabin. You can tell by the scorch marks in one area that a cookstove was there. You can spot where they drilled and chiseled out pockets to incorporate conduit boxes for electricity.

I kept and pounded in as many of the original nails as I could. I needed to keep touchpoints of the cabin’s history, as if it were a living character, so it would retain its own memories.

Photo: Melissa Lukenbaugh

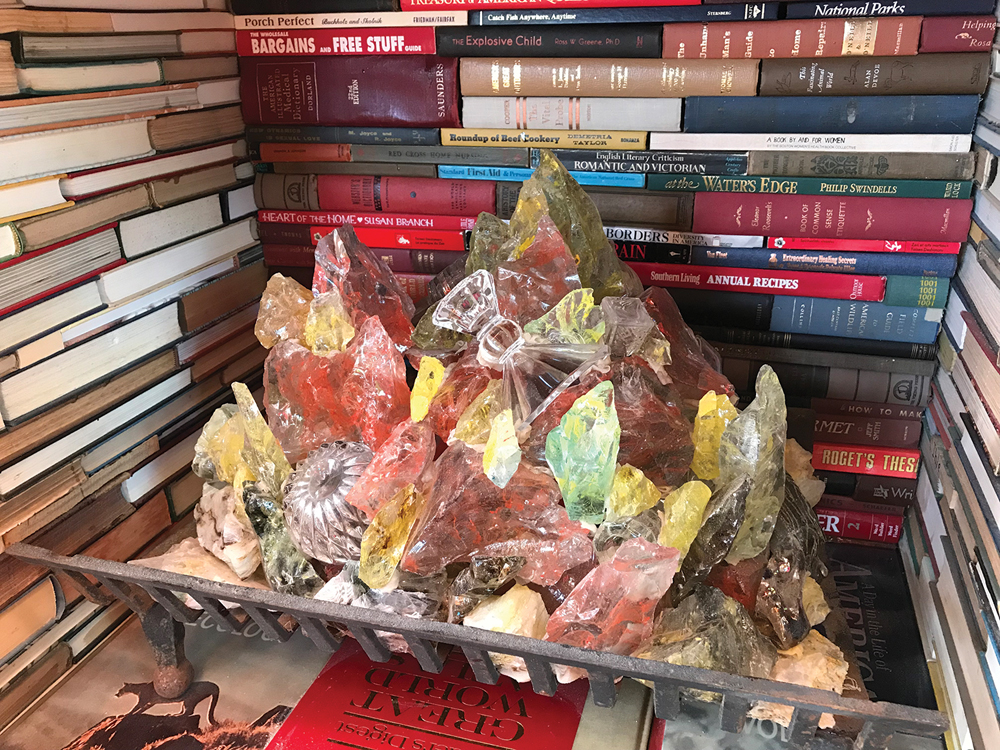

In southeast Minnesota, we have a lot of limestone the same color as weathered paper. That inspired me to build a chimney of reclaimed books collected from myself, neighbors, friends, and folks down in Tulsa. I stacked them the same way you stack limestone, then sealed them in place with resin.

I like thinking about how it’s gonna require some alien technology to pull this chimney apart, read the books, and find out about the human race. A lot of the titles are on natural history and the rural experience. The mantel is made of thick reference books on architecture, art history, nature, and anatomy; there’s even a dictionary.

And toward the top, the cracks start to widen, resembling the desktops of obsessive researchers, where books are stacked in organized chaos.

If you walk to the left of the fireplace and look closely in the corner of the doorway and the wall, you might spot a beer-can label I left visible. (To record where the logs fit, we took apart aluminum cans, scratched markings on them, and attached them to the logs.) About five years back, I was sorting out the puzzle of fitting the cabin together at my studio, and a young boy would come help out. His name was Hunter Bergo. At the time, he lived next door, and I’d put him to work on a little of this, a little of that. He scratched almost all the original ID tabs. But a few years ago, he died in a four-wheeler accident. He was only about 10 years old. That visible label is a tribute to him and is one of the most important parts of Slumgullion to me; the echo of Hunter’s hand is in the letters on that tag.

Photo: Nicole Huss

I made the fake fire with shards I glued together from tchonk (scrap and reclaimed) glass. Look closely, and you’ll also find found objects such as butter dishes and egg cups slumped in the fire. I try to incorporate these types of Where’s Waldo? hidden-picture, seek-and-find things in all of my work.

Photo: Nicole Huss

I made the ceiling and roof ostentatious to get people to look up, literally and metaphorically. It’s something people don’t do a lot of nowadays.

In the wall behind the chimney is a “bookshelf” that’s actually a door. Pull the book that serves as the latch, and it pops open. But you might be disappointed to look inside: It’s where the electrical system is hidden.

Photo: Nicole Huss

The ceiling’s designed to scream at you when you walk in the cabin, and then, after that, become like this symphony of Zen. It’s made from old work shirts I collected from my own closet and those of friends and family. Also thrift stores. I dipped the T-shirts in polyvinyl resin, let them set up, and then laid them as shingles over clear polycarbonate decking. They’re a tribute to all of the shirts you wear when you go and work on the farm – you don’t grab anything fancy.

The patchwork effect also hearkens back to all of the quilts that my grandma Avis made for us grandkids. Though it’s seen better days, I’ve still got mine.

Photo: Nicole Huss

Over 180 lanterns hang from the ceiling, and there’s not any two alike. They’re made of glass bottles collected from my hometown and donations made to the Philbrook Museum. Each has a little flicker bulb that I remember from people’s homes in the 1970s, this accent fixture that didn’t really generate light but did generate decoration.

Photo: Nicole Huss

Recycled glass bottles are slumped into the stained-glass windows. Everything, including the way the light plays through the glass and hits the floor, is intentional.

Photo: Nicole Huss

For a few years now, I’ve been slumping large bowls, bottles, and other difficult-to-bezel objects into stained-glass windows. Some pieces retain the fluting and the foot. Some, the handles are still visible.

The glass may be recycled, but the floorboards are made with fresh-cut wood from Fillmore, Minnesota. A guy by the name of Andy Erding runs a sawmill there that he took over from his father after he passed. All of the wood for the floorboards was cut and collected from southeast Minnesota, and I hauled it all down to Oklahoma, straight from the mill.

Photo: Nicole Huss

Take in the colors between the logs. What you’re looking at is not light leaking through; it’s lighting incorporated within the walls. I threaded LEDs through acrylic tubes, then placed them between the logs, where the chinking and daubing normally would be. That’s a craft unto itself, by the way, plugging in the gaps between the logs and insulating the cabin. Typically, people used concrete, moss, mud, plaster, dung, stone, cloth – whatever was on hand. Here I used recycled T-shirts. All were hand-dipped in resin before being tucked in. They’re partially a reference to the Dust Bowl and all the rags that people tucked into their homes to keep the dust out. It took two assistants hours and hours to fill all of the cracks of this home.

Photo: Nicole Huss

The table and benches are made by an Amish fellow in Harmony, Minnesota. Name’s Abraham Hershberger. This is what he called sarsaparilla wood. He made everything by hand, just by following a drawing that I gave him. I said, “I want you to make these. Don’t worry about them being sanded well. Make them look like they needed to be done quickly, before winter.” He gave me a wink and says, “No problem.”

Karl Unnasch, 49, at work on stained-glass elements for Slumgullion (The Venerate Outpost) (2018) in his studio near Lanesboro, Minnesota. Photo: Nicole Huss