Clay Tells All

Clay Tells All

Cruise the galleries of any encyclopedic museum and you’re bound to come across clay vessels and figures that tell of cultures past. The 15 ceramists here, nominated by a panel of artists, curators, educators, and collectors, show how the drive to document our time in clay remains as strong now as it was hundreds, even thousands, of years ago.

In a range of approaches, many of the artists push for change, seeking to raise awareness of social, political, and environmental issues. Others celebrate the everyday in delightful, sometimes absurdist, ways. Humor abounds in the work of many, often with an edge. Several fuse pop-culture references with time-honored symbols, stories, and techniques, showing both how much and how little has changed. What remains constant: The stories they tell. ~The Editors

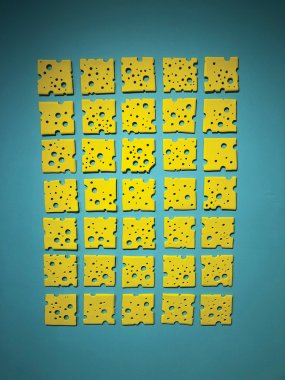

Nick Lenker, 36, Philadelphia

Years working with clay: About 20

What drew you to the medium? The malleable and transformational qualities of the material were what kept me coming back.

Where do the stories in your work come from? Why do you tell them? My goal with these objects is to have them comfortably exist in both a physical and virtual environment. The process is an analog version of how three-dimensional objects are rendered within virtual environments. The object is wrapped in photographic textures, helping them appear real, although the form is somewhat crude. They try to be something they are not; you could call them fake. I find this to be analogous to how we curate our identities through images on platforms like Instagram. We are affecting how we are perceived by curating images describing our lives and how we see ourselves or how we wish to be seen.

I’m also interested in talking about perspective within these objects. We now can see the world from a multitude of first-person perspectives; will this help us empathize with one another, or will it lead to mere objectification?

Jami Porter Lara, 49, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Years working with clay: 6

Preferred clay: Clay that I forage from a site near my home.

Preferred techniques: I forage clay, hand-build with coils, burnish, and pit fire. I first learned these techniques, which have been in continuous use on this continent for thousands of years, in a workshop with esteemed potters Graciela and Hector Gallegos of Mata Ortiz.

Where do the stories in your work come from? While exploring a remote stretch of the US-Mexico border in 2011, I found 2-liter bottles used to carry water – the most recent in a lineage of artifacts that remain from millennia of human travel through the region. Using these found objects as source material, I sought to reconceptualize the plastic bottle to better represent its function as a precious object – a vessel – capable of sustaining human life.

Why do you tell them? My hope is to illuminate the necessity that leads to the ubiquity of these objects; to expose the porous nature of borders as well as the nature of art and garbage; to record my interest in the permeability of all things human, natural, and technological. Art is also my attempt to be someone that the world needs – by the counterintuitive tactic of making something that no one needs. It is my refusal to say that the Earth would be better without me and the determination to prove that claim wrong.

Anita Fields, 67, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Years working with clay: 45

What drew you to the medium? The immediacy, the transformative qualities, the endless possibilities. It took me back to my childhood memories of making mud pies under the hot Oklahoma sun.

Where do the stories in your work come from? The stories I express come from a multitude of places: childhood memories, experiences, dreams, social issues, everyday encounters, family stories, and the narratives found in the culture and history of Osage people.

Why do you tell them? The work I make signifies a continuum of thought, knowledge, and the essence of who we are as indigenous peoples living in a modern, chaotic, and challenging world. I want to dispel the many myths and stereotypes surrounding Native people and cultures, and convey the beauty and importance of other cultures and the thought that there are many ways of looking at the world.

Much of the work I create reflects the early Osage notions of duality, such as earth and sky, male and female. By articulating the concepts of balance and the symbiotic relationships found throughout life and nature, I hope to deepen our understanding of the intersection of all living things.

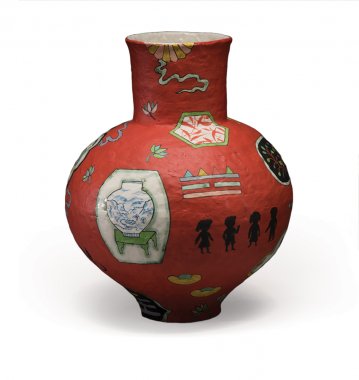

Beth Lo, 69, Missoula, Montana

Years working with clay: 48

Preferred clay: New Zealand porcelain (I like its whiteness and how brightly colors show up on it.)

Preferred techniques: Slab, coil, throwing, slip-casting

Where do the stories in your work come from? My work primarily revolves around the family and my Asian American background. Cultural marginality and blending, tradition versus Westernization, and language and translation are key elements. Since the birth of my son in 1987, I have been drawing inspiration from major events in my family’s history, the day-to-day challenges of parenting, and my own memories of being raised in a minority culture in the US. I use the image of a child as a symbol of innocence, potential, and vulnerability.

Describe your work: Personal, narrative, socio-political

Pattie Chalmers, 53, Carbondale, Illinois

Years working with clay: About 25

Preferred clay: I am an equal-opportunity ceramicist, but have been working primarily with terra-cotta for the last couple of years.

What drew you to the medium? The trifecta of shape, form, and surface.

Where do the stories in your work come from? The compositions I fabricate depict a shrinking of the distance between fact and fiction, another perspective from memory enriched by imagination: Accounts from a parent, a teacher, a movie, or a dream – fragments exaggerated or diminished, twisted together in an order that corresponds with the flux of how things are remembered.

Why do you tell them? I am inherently a storyteller. I try to map experience as a way to gain a better understanding of others and myself.

Describe your work: Earnest, clumsy, mutable

Courtney M. Leonard, 38, Shinnecock Nation

Years working with clay: My whole life, but I don’t distinguish personal experience from cultural or familial experience. I am honored to acknowledge those who came before me.

What drew you to the medium? Devotion, discovery, and determination. Clay in many ways mimics life. Although I work in many materials, from video to performance to installation, clay grounds me.

Preferred materials and techniques: As questions are posed about environmental sustainability, I have chosen to explore the ephemeral, no longer firing clay but instead exhibiting it in its raw state, only to be deconstructed, reclaimed, and reused again.

Where do the stories in your work come from? Why do you tell them? Shinnecock translates in English to “people of the level land” or “people of the shore.” As a small coastal community, we are dealing with environmental concerns including rising waters, coastal erosion, toxic shellfish, and nitrogen run-off as well as challenges to our fishing, water, and land rights. We also maintain the cultural stewardship of our land and resources, including whales. Traditionally, one beached whale would feed our community through winter; now, many people outside of our community see feeding on whales as unethical. In my practice, I’ve come to think of myself as a visual whaler, logging an account of what is happening above and below the waterline. The question that persists in my ongoing project, Breach, is “Can a culture sustain itself when it no longer has access to the environment that fashioned it?”

Describe your work: Indicative, resilient, devoted

Kukuli Velarde, 55, Philadelphia

Years working with clay: 27

Preferred clay: Low-fire terra-cotta

Preferred technique: Coiling

What drew you to the medium? Its historical connotations and the possibility of connecting with my ancestry.

Where do the stories in your work come from? Why do you tell them? I believe art has an inherent power to both reflect and influence society. It is a mirror and a tool for change. I hope my work speaks of difference and justice, calling attention to historical ethics and recognition of plurality in the world. I hope my work brings audiences to question the universality of Western aesthetics and starts a conversation about the necessity of understanding the right of every cultural manifestation to exist independently or in contrast to Western beliefs.

Describe your work: Personal, committed, free

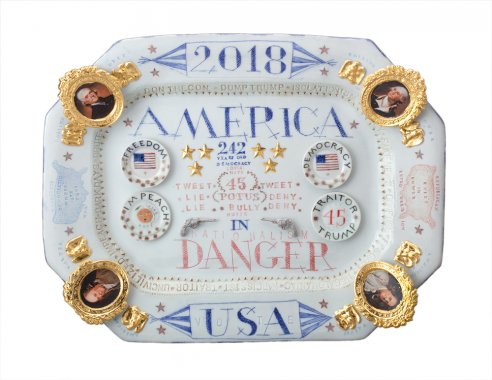

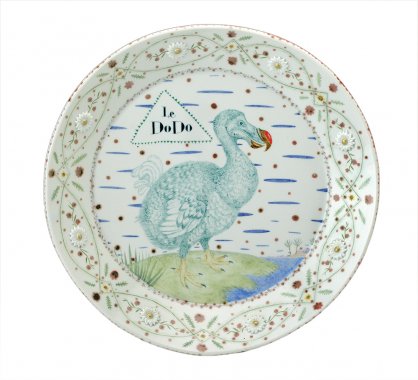

Mara Superior, 58, Williamsburg, Massachusetts

What drew you to the medium? I was drawn to porcelain as a three-dimensional painting surface, for its historical connections to Europe and China, and its beauty.

Where do the stories in your work come from? My work is autobiographical; therefore, whatever I am most interested in at a given time will inevitably show up in it. I am inspired by history, art history, architecture, travel, research, and my life experiences – from the pleasures of the domestic to contemporary art to current political events.

Why do you tell stories? Artists address the pleasures or frustrations we commonly feel [through] tangible objects. Through this work we are hopefully able to connect with a larger audience and have a say in the human condition. I love my job. So many projects, so little time!

Describe your work: Personal, idiosyncratic, beautiful

Diego Romero, 54, Santa Fe

Years working with clay: 35

Preferred clay: Earthenware, both commercial and that which I find and mix by hand.

Preferred technique: Coiling, which is how most Pueblo pots have been made since the beginning.

What drew you to the medium? At 19, I showed up to study at the Institute of American Indian Arts. A counselor suggested that I take a traditional pottery class with Otellie Loloma, a Hopi woman and renowned potter. She became like my grandmother, and I have been making traditional pottery with the techniques she imparted ever since.

Where do the stories in your work come from? My work is a narrative on the absurdity of human nature. I’m influenced by contemporary Cochiti Pueblo pottery, comic books, pop culture, and Greek vessels.

Why do you tell them? I think that laughter is medicine; we have to be able to laugh at ourselves and the absurd in order to heal. My ultimate goal is to educate and heal and bring lightheartedness into people’s lives.

Describe your work: Political, humorous, timeless

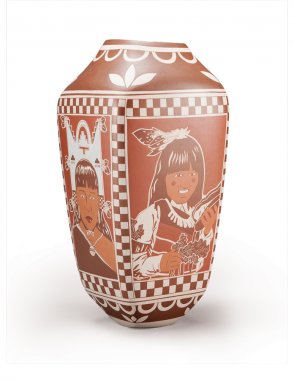

Virgil Ortiz, 49, Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico

Years working with clay: 43

What drew you to the medium? I was born into a family of potters. Clay was always around my siblings and me; it was part of everyday life. My grandmother, Laurencita Herrera, and mother, Seferina Ortiz, were both renowned Pueblo potters and part of an ongoing matrilineal tradition.

Preferred materials and techniques: I was taught using traditional methods and materials: Cochiti red clay, red and white clay slip, and the wild spinach plant (used for black paint). This process has been an integral part of my lineage for hundreds of years. My figurative work reflects the style and subjects that were created in the late 1800s. Most people do not know about these figures or how contemporary-looking they are.

Where do the stories in your work come from? Why do you tell them? Historic Cochiti clay figurative works were based on social commentary, capturing a timeline and caricatures of the newcomers arriving on Native land. I have dedicated my life to reviving these historic pieces using the exact same methods and materials; only the time and subjects have changed.

Describe your work: Cultivate, revive, educate

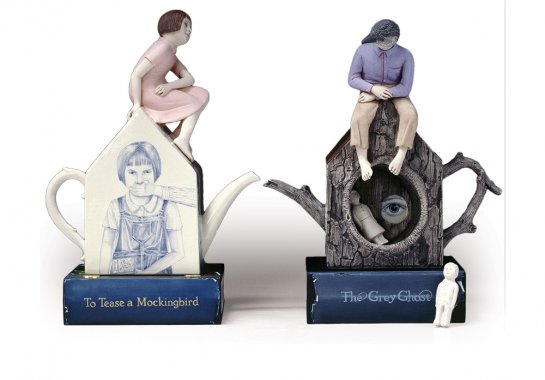

Red Weldon Sandlin, 61, Decatur, Georgia

Years working with clay: 31

Why is the teapot your primary form? It lends itself to a host of possibilities and is the perfect narrative form, since it can be read by rotating it. I handle teacups the same way: Tell a story start to finish by merely turning it. Spouts and handles can be arms, twigs, hair braids, tails, or even a suggestion of male anatomy. Teapot bodies can be anything from bodies, heads, or even whole caterpillars. Lids can often be a surprise reveal when removed.

Where do the stories in your work come from? Why do you tell them? The narratives come from the stories I read as a child, mixed with life’s experiences. My hope is that I am presenting work that the viewer will be drawn into. Initially it appears fun and familiar, but on further inspection there is more to discover – like a good story.

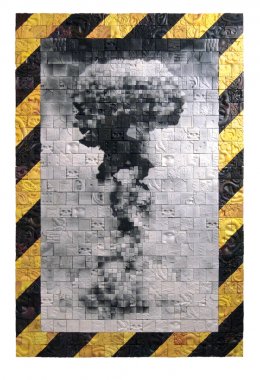

Richard Notkin, 70 (and “still kicking”), Vaughn, Washington

Years working with clay: 50 (“The best therapy I can imagine. It’s kept me semi-sane.”)

What drew you to the medium? Fear of solvents and a sense that I could finally have control over something on this planet. Plus an amazing ceramics program at the Kansas City Art Institute.

Where do the stories in your work come from? A lifelong desire to end the insanity of war. Early influences include testimony from Holocaust survivors at my family’s synagogue in the early 1950s, the near nuclear annihilation posed by the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962 (I was 14 years old), protesting the disastrous war in Vietnam, and the continued misguided military actions by nations around the world. Add to all of that the rise of racism, xenophobia, white supremacist politics, a worldwide tilt toward fascism, and – perhaps most dangerous of all – the existential threat to humanity’s future posed by global warming.

Why do you tell them? There is a lot to be angry about in this world; I deal with this anger by making art. I hope to awaken others – especially young and emerging artists – to be alert, aware, and active; to express their concerns in whatever media they choose; and to vote in every election.

Describe your work: Detailed, poetic, angry

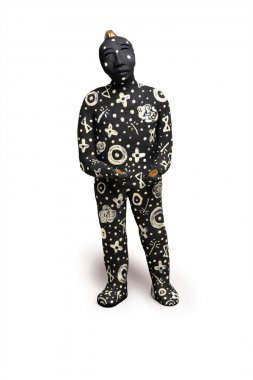

Nathan A. Murray, 36, Lincoln, Nebraska

Years working with clay: 11

What drew you to the medium? Gail Kendall’s beginning ceramics class at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. I came from a background in drawing, and the possibilities of three-dimensional work appealed to me. An object that you can move around and interact with from different angles opened up many opportunities for storytelling and emotive expression.

Where do the stories in your work come from? Why do you tell them? Many are inspired by my own life experiences or those of people I’m close to. I use these stories to speak to challenging societal issues in the United States. My 2016 exhibition “Color Theory,” for example, explores how being black in America is often perceived as a threat.

Art is a powerful tool that has the ability to effect positive societal change. My figurative sculptures are representations of unique individuals and their stories. My intent is to celebrate multiculturalism and diversity. It seeks to connect with the viewer and spark discussion.

Describe your work: Emotive, contemplative, personal

Christina Erives, 29, Helena, Montana

Years working with clay: 8

Preferred clay: Terra-cotta, earthenware

Where do the stories in your work come from? My Mexican heritage and family traditions. My interest in creating these objects arises from my fear of traditions being lost. I hope to render a narrative that embraces and celebrates the rituals of a new generation. Ceramics as a material has permanence; it is one of the ways we were able to learn about ancient cultures. There is beauty in these traditions, and my aim is to make a mark in my time that will be preserved in the history of ceramic objects.

Describe your work: Colorful, nourishing, playful

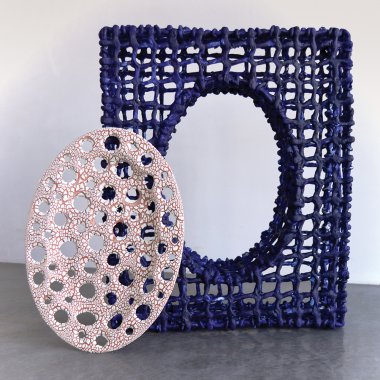

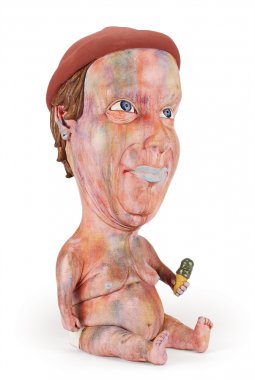

Travis Winters, 33, Uniontown, Pennsylvania

Years working with clay: About 14

What drew you to the medium? It's tactile nature. Also, the science behind clay, glaze, and the firing process has always intrigued me. Although clay can easily be manipulated into any form, it takes a firm understanding of these technical aspects to build and finish work.

Where do the stories in your work come from? The stories are based on mundane, day-to-day life experiences, past and current struggles, and real people. I create pieces around themes that I find humorous, confusing, or sometimes even terrifying. These stories can be based on anything from my own personal dilemmas with eating meat to the things people do while driving to a fascinating person I met.

Why do you tell them? I hope to captivate viewers’ imaginations. I want them to fabricate their own narratives and form relationships with the characters. By creating comical figures, I’m attempting to initiate a non-threatening conversation about a variety of topics ubiquitous within our culture.

Describe your work: Humorous, grotesque, visceral

Contributors

Garth Clark, editor in chief, CFile; Leslie Ferrin, director, Ferrin Contemporary and Project Art; Beth Ann Gerstein, executive director, American Museum of Ceramic Art; Ayumi Horie, studio potter; Garth Johnson, curator of ceramics, Everson Museum of Art; Jessica Knapp, editor, Ceramics Monthly; associate editor, Pottery Making Illustrated; Cannupa Hanska Luger, artist; Sarah Millfelt, executive director, Northern Clay Center; Bobby Silverman, artist and designer; director, 92nd Street Y Ceramic Center; Michael J. Strand, artist; professor and head of visual arts, North Dakota State University; Jennifer Zwilling, curator of artistic programs, the Clay Studio