Cloth Encounters

Cloth Encounters

In Ocelot’s silk top and wrap skirt, hemp cotton sailor trousers, and wool shrug, the warmth of the sunset is evoked by layering natural dyes in yellow hues with the red of madder root. Photo by Angelina DeAntonis.

In a culture as diverse and complex as that of the United States, artists who choose to express their ideas through textiles make use of the powerful messages that textiles communicate to great effect. This exciting field, dominated by women, is currently grappling with issues of environmental, economic, and social sustainability. Many makers are choosing to develop the possibilities of recycled materials or to employ a field-to-fabric approach, which encompasses aspects of animal husbandry and land management. Others grapple with the textiles’ uncomfortable history and explore ideas of identity. All use astonishing creativity to craft a brighter future.

As the founder and editor of London-based Selvedge magazine, it has been a privilege to spend my career promoting makers working with textile materials. For this issue of American Craft, I’ve selected several American makers to watch, some new to the field and others with a lifetime of experience. Enjoy!

~Polly Leonard

Amy Revier

Amy Revier with her restored Harris Floor Loom in London at the gallery space Blue Mountain School, exhibiting one-of-a-kind woven coats over London’s Frieze Art Fair, 2016. Photograph by Jake Curtis.

Amy Revier is a Texas native currently based in London, part of a new generation of artists exploring the garment form. Revier studied art history and sculpture, with a focus on the relationship between form and performance. “I spent a lot of time thinking about wraps,” she says. “Head wraps, body wraps, and how the body worked within and out of them.” In her Hampstead studio, Revier creates one-of-a-kind coats on a traditional Scandinavian wooden floor loom. The correlation between her academic interest and current practice seems obvious when you see her working at her loom; the process of weaving becomes a performance of making in itself.

Installation of Amy Revier’s one-of-a-kind, double-weave, reversible coats in handwoven, handspun and hand-dyed Highlands cashmere. Blue Mountain School, London, 2019. Photo courtesy of Amy Revier.

Revier’s work questions traditional boundaries between art and craft. Are these coats made to be hung on a wall or worn? They’re “signed” rather than labeled, collected rather than bought, and made with an attitude more often seen in fine artists than in craftspeople. “I want to push away from the fashion world,” she says. “I’d love to install sculptures among the clothes.” If you’re lucky enough to own one of Revier’s coats, it will be a soulmate in your wardrobe.

Rhiannon Griego

Rhiannon Griego wearing her Rainbow Ways Cape, made of handspun wool, silk,Tencel, Lurex, and cotton. Photo courtesy of Rhiannon Griego.

Saori is a philosophy of weaving that promotes freedom, improvisation, and self-expression. It’s based on the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi and emphasizes the acceptance of imperfection. In saori, whatever is woven is perfect as it is: broken and repaired warp threads, lumpy selvedges—these irregularities represent the uniqueness of the handmade cloth. Rhiannon Griego, a Santa Fe–based artist, marries this philosophy with the rich weaving traditions of her Mexican, Spanish, and Tohono O’odham lineage to create boleros, ruanas, tunics, and capes from undyed, hand-spun silk, indigenous cotton, Churro wool roving, and horsehair. The color, texture, and form of her work are reflective of and inspired by the desert landscapes of the Southwest, where she sets up her loom and weaves outdoors. Griego has a respectful approach to her materials and technique, as reflected in her garments constructed from uncut cloth. These garments reflect the zero-waste practices of Indigenous weavers around the world.

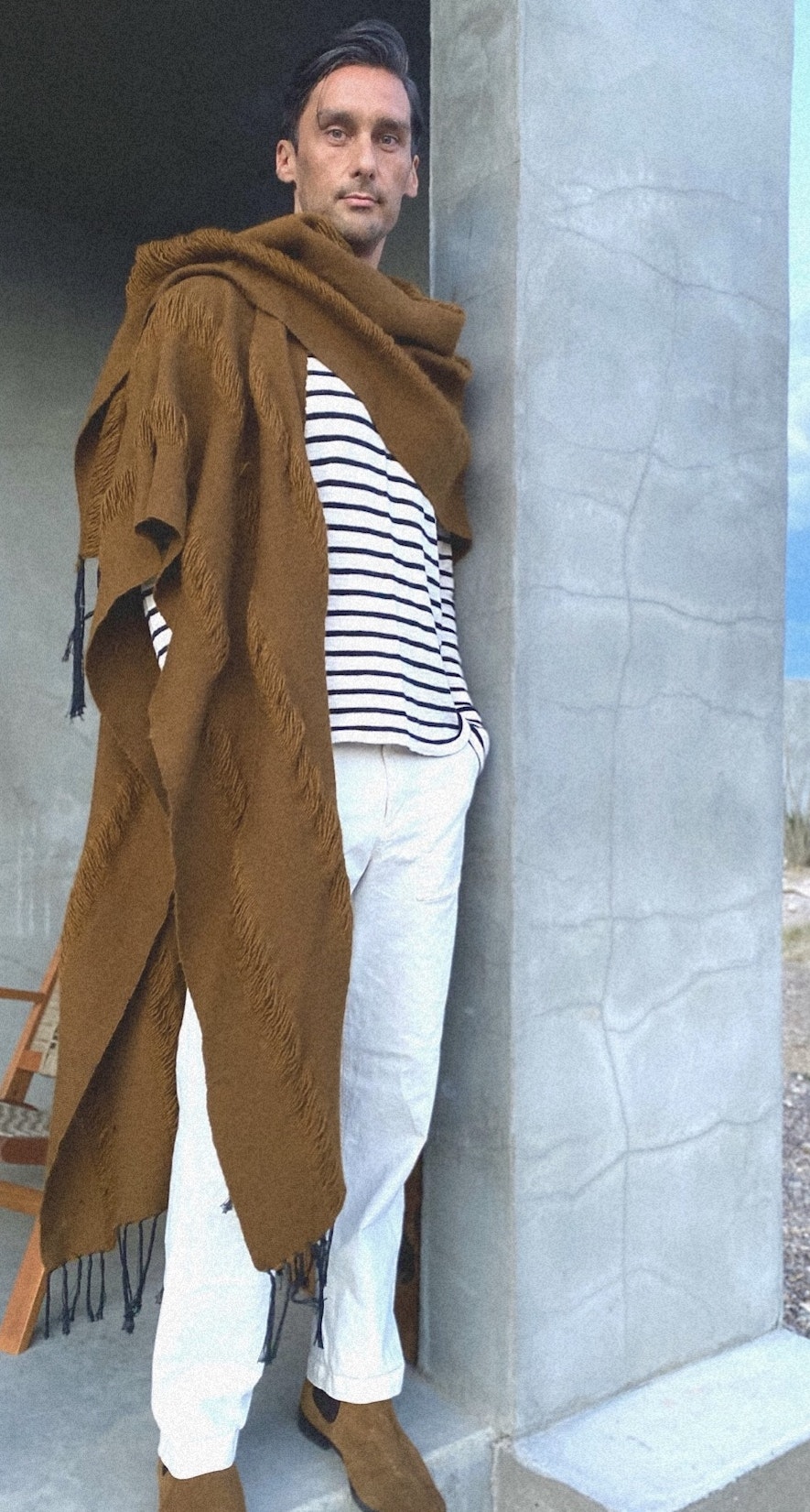

Griego’s merino wool unisex Tobacco Drape Cape is handwoven with “empty reed dents between threaded harness.” Photo courtesy of Rhiannon Griego.

Cara Marie Piazza

New Yorker Cara Marie Piazza is a modern-day alchemist working with botanicals, plant matter, minerals, nontoxic metals, and food wastes to create fabrics that are respectful of the environment. By employing a vast array of techniques, including ombré, shibori, batik, bundle dyeing, rust dyeing, and hand-painting, she casts her spell over the textiles of private clients and designers alike. Catch her workshops, including a remarkable combination of cooking and dyeing called “Eat Your Colors” with Chef Elisa Da Prato. Da Prato, who is known for using flowers and other botanicals in her Tuscan restaurant, Elisa, joins Piazza to cook herb-pressed pasta and rose petal ravioli and ricotta, and then dye a set of napkins with leftover herbs and roses, pomegranate rinds, and a variety of kitchen spices. I love Piazza’s approach to creating uncompromising color treatments without compromising the environment.

caramariepiazza.com | @caramariepiazza

LEFT: From Cara Marie Piazza’s intimate label Calyx, pants dyed with logwood and iron. Photo by Eric Herman. RIGHT: This dress, shown in a Jason Wu runway show, features digital re-creations of hand-painted silks that have been dyed with lac beetle, frozen flowers, marigold, and ice. Photo courtesy of Cara Marie Piazza.

Christina Kim

Christina Kim loves working with her hands. She started Dosa as a creative experiment, a conversation between commerce and handmade clothing, pioneering slow fashion at every turn. Within 10 years she was questioning the traditional industry methods, and her in-house team added handwork techniques to their repertoires. Her Standard Issue line is made up of nonseasonal, value-led garments based on vernacular clothing and inspired by the rabari shepherd jacket, the kurta, the cossack top, and the dashiki. Committed to artisanal, heritage techniques such as Bandhani and Leheriya, developed by the Khatri community of Gujarat in India, and a zero-waste philosophy, Kim favors organic, natural-dyed, handwoven cloth and hand-stitching when collaborating with artisans from places as diverse as Mexico, India, China, and Colombia. An accomplished gallery artist as well as a clothing designer, she recently closed her store in New York to reduce her footprint and amplify her message through museum installations across the world. She has been a leader in the field for 35 years and continues to challenge the status quo in everything she does.

TOP: The first-generation jamdani choga and slip, 2007, are made from hand-spun, hand-woven, cut and sewn brocaded cotton jamdani saris. BOTTOM: The second-generation jamdani, Eungie skirt in satyajit color, 2008, is made with jamdani scraps that are pieced, reverse-appliquéd, embroidered, cut, and sewn. Both pieces are part of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, © Dosa Inc.. Photos © Christina Kim.

Katherine Edmonds

Wovenplay is a children’s wear brand providing “creative couture for the everyday artist and adventurer.” Founder and designer Katherine Edmonds has a background in art, textile design, and traditional French dressmaking. Using heirloom techniques, such as hand-dyeing and silk-screen printing with water-based paints, to highlight the tactile qualities of natural materials, Wovenplay cultivates the savoir faire of the past to create modern clothing and accessories for a life lived with imagination. All collections are made by hand in Wovenplay’s Brooklyn studio and tinted in natural or low-impact dyes. The garments are constructed to the highest standards by a local workforce or fair-trade producers abroad, and packaging is recycled and/or biodegradable. With its delicate dresses and hand-printed capes, Wovenplay inspires creativity and appreciation of the inherent beauty of traditional arts and crafts.

RIGHT: This Wovenplay tutu is made from duchesse silk satin from a mill in England and has textured tulle ruffles. The cotton hood has flowers screen-printed by hand and vintage beads on the sides. Photo by Hannah Scott Stevenson.

Of all the horrors of “fast fashion,” polyester and other petroleum-derived, nonbiodegradable materials—seen everywhere in the contemporary wardrobe—are perhaps the most abhorrent to the aesthetically and environmentally conscious. Wovenplay provides a welcome antidote: responsibly made garments that also help nurture the creative minds of the future.

LEFT: This tutu, also made from duchesse silk satin, features a vintage striped silk ribbon from France. The featherband has hand-dyed feathers and vintage Italian beads. Photo by Alexandrena Parker.

Sarah Nsikak

This patchwork dress, inspired by Sarah Nsikak’s Nigerian heritage, is made of natural fibers, both vintage and deadstock. Photo by Richie Jo.

Sarah Nsikak, a Nigerian American living in Brooklyn, New York, unites her cultural heritage with contemporary style in her brand, La Réunion. Nsikak was taught to sew by her grandmother, a seamstress in Nigeria, and her inherited love of textiles led her to work in the fashion industry for several years after completing training in art therapy. Then her concern about the waste generated by the industry prompted her to return to her art practice to make implicit statements about sustainability. Nsikak’s patched dresses are made with materials sourced from the floors of cutting rooms in New York City.

Photo by Kate Berry.

She is interested in reclaiming beauty from the ugliness of the past, explaining that “when beauty has been stolen by way of colonization . . . it is up to the artists and makers of that place to reclaim it.” Her work is influenced by the vibrant stories of African culture, particularly the tale of how the Herero people reimagined German clothing. Authorities in the colony of German South West Africa (now Namibia) tried to wipe out the Herero in the early 20th century—but their descendants got a kind of revenge by appropriating and reimagining the European clothing styles of their oppressors, thoroughly Africanizing them in the process. It is a sign of resilience—what people from the African diaspora around the world have been practicing for centuries. To make emphatically beautiful something that was initially a symbol of pain and suffering is an act of rebellion and a sign of immense strength.

Even though she doesn’t consider herself an art therapist, Nsikak acknowledges the healing properties inherent in the methods she uses in her work. Her courage in grappling with an uncomfortable aspect of our shared history is palpable in her work.

Angelina DeAntonis

Ocelot's tundra wool blanket skirt with cashmere scarf, 2021, are dyed in all-plant dyes in colors that reflect the drying grass transitioning to winter. The extra thick wool of the wrap skirt is so dense and fulled that it doubles as a couch throw. The darker ochre-orange comes from madder root grown in the foothills of the Himalayas. Photo by Aaron Davidman.

Angelina DeAntonis is a Bay Area–based maker. Her company, Ocelot, specializes in hand-dyed clothing constructed from cotton jersey knit fabric. Bold and luminous patterns emerge from precision engineering in the dye studio, and these are crafted into placement-dyed garments in subtle autumnal hues. DeAntonis employs itajime, an ancient Japanese clamp resist-dye technique. The laborious, physically demanding process requires several days to complete. It involves folding the fabric carefully, then placing wood blocks (DeAntonis uses disks) on either side of the folded fabric. Pressure is then put on the blocks by binding and clamping. When the bound fabric is immersed into the dye bath, the mirroring process created by the folds makes rhythmic patterns, and the background becomes a field in which the luminous resist-dyed circles glow. These circular forms haunt her work. For the past 20 years DeAntonis has devoted her career to developing this visual language, using the vocabulary of the circle and the grammar of natural dyeing to make strong personal statements.

ocelotclothing.com | @ocelotclothing

The wool used for this shrug and wrap skirt, 2005, were milled in the US and dyed in a base layer of natural dyes. These layering garments are created to customize an otherwise plain outfit with patterns suggesting an animal, a visceral reminder of our connection to nature. Photo courtesy of Angelina DeAntonis.

Sveta Dresher

Sveta Dresher opened the charming whitewashed brick-and-mortar store Pip-Squeak Chapeau in September 2009 in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. The Pip-Squeak Chapeau line—still handmade by artisans in Brooklyn but now sold at Drescher’s Pip Country Shop in Callicoon, New York— features seamless hand-felted wool skirts, cozy mohair sweaters, linen shirts, dresses, and scarves. Using only natural yarns and fabrics, such as cotton, hemp, silk, and alpaca, the artisans’ skilled and creative work benefits consumers who seek a more ethical community and a healthier environment. With no age or size restrictions, these body-positive clothes are less about fashion trends than about the way their wearers move through life. The poet Maya Angelou once said, “I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” Dresher’s garments will be remembered for making the wearer feel good.

Sally Fox

An iconic figure in the fashion industry, Sally Fox has been spinning, knitting, and weaving since childhood. It was her passion for making that led her to see the market potential for long-staple organic cotton. It was the financial support of the crafting community that allowed her to quit her job as a scientist and devote her life to developing open-pollinated varieties of cotton. Heirloom cotton was once abundant and grew in a rainbow of shades, including green, yellow, blue, and brown. Fox did what no one thought possible: she crossbred ancient, naturally pest-resistant varieties of this colored cotton with standard long-staple cotton. These hybrid types could be grown using organic, pesticide-free farming methods and, unlike the old varieties, had staple lengths long enough to allow the fiber to be machine spun into high-quality yarn. Each of the four types she developed—Redwood, Coyote, New Green, and Buffalo—took a decade of crossbreeding before it could be brought to the market.

.jpeg?auto=compress&cs=srgb)

Photos courtesy of Sally Fox.

The result was a revolution; it made organically grown, naturally colored cotton available through Vresis Limited to a new generation of designers who wanted to avoid the environmental damage caused by pesticides and chemical dyes. The “slow fashion” movement, with its hand-spun fibers, can be elitist and cost-prohibitive for conscious consumers; but by democratizing Indigenous cotton Fox hopes to make it an economic reality for all. Getting these spectacular cottons into mainstream industry use remains her ultimate goal.

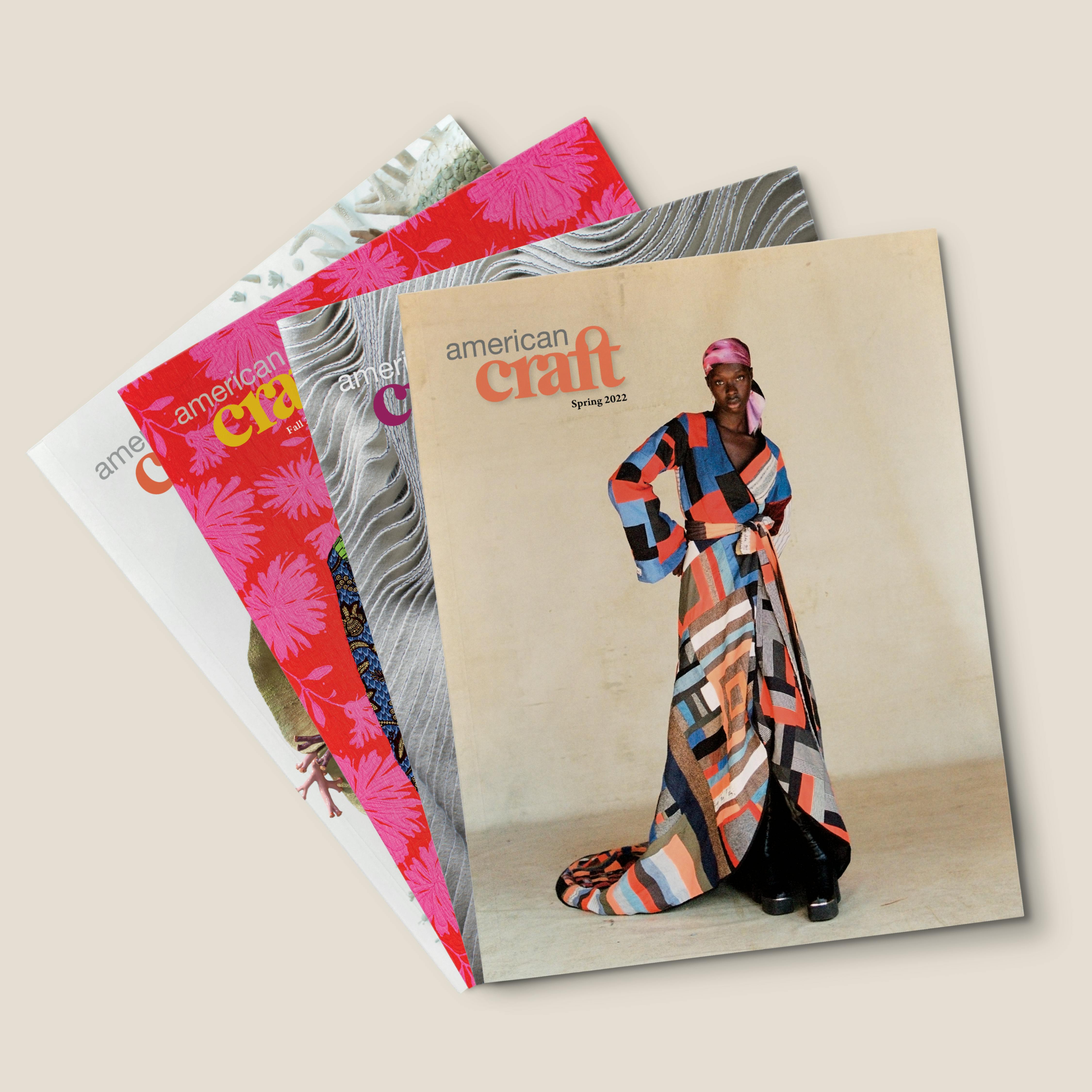

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.