Encountering Alice Kagawa Parrott

Encountering Alice Kagawa Parrott

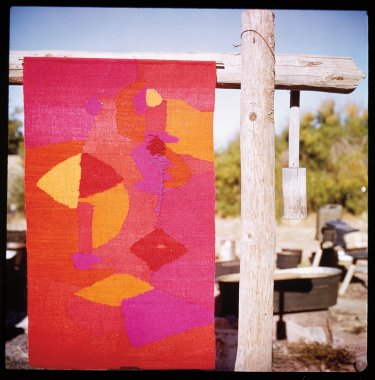

When artists are gone, we usually have two ways of getting to know them visually: through their work, and through photographs or films documenting them or their studio. Alice Kagawa Parrott, a fiber artist, ceramist, and ACC Fellow, died in 2009, at 80. Though there is something bemusing about accomplished artists – particularly women active in the middle of the 20th century – being “discovered” by style-seekers on the internet, Parrott’s work is indeed enjoying a well-deserved resurgence of interest, with articles appearing in the past several years on the Gravel & Gold collective’s blog and Esoteric Survey. Her color sense and the pastoral beauty of her home and studio are enormously appealing and feel contemporary: She clearly loved magenta, and her indoor-outdoor workspace looks chic, unpretentious, and dreamlike. Her work was featured in the Museum of Arts and Design’s 2015 exhibition “Pathmakers: Women in Art, Craft and Design, Midcentury and Today.” Yet even in the studio craft world, Parrott’s name is less recognizable than those of Sheila Hicks and Lenore Tawney, or Ruth Asawa and Toshiko Takaezu, her friends from Cranbrook in the early 1950s.

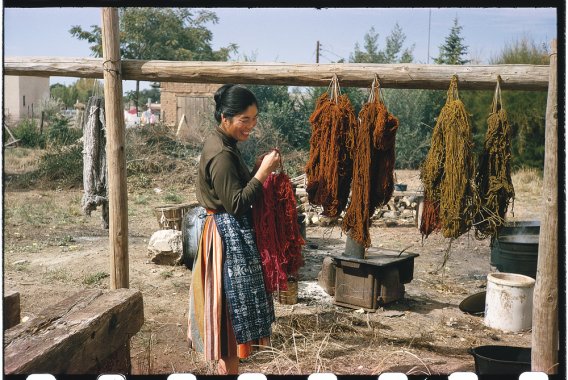

My own first encounter with Parrott was, happily, analog. The American Craft Council’s library houses innumerable slides from the era before digital photography. Vintage slides are like a tangible Instagram feed from another era, and the scenes they capture have a heightened, almost surreal degree of saturation. This format makes the slides of Alice Parrott’s Santa Fe home studio spring to life, even when one squints to see them without a projector. Shot in the mid-1960s, the images capture Parrott at work for a photo essay displayed at the Craft Council’s Pavilion of American Interiors at New York’s 1964 World’s Fair. Set against the adobe walls of her house, her geometric-yet-woolly wall hangings radiate yellows, pinks, reds, and deep blues. In other slides, we find her working with her husband, Allen, a curator at the Museum of International Folk Art, boiling plants to make dye for coloring her yarn by hand. Indoors, she works at her loom and spins yarn. She wears brightly colored clothing made from her own weaves. She smiles or looks down intently as she works.

Parrott was profiled in the July 29, 1966, issue of Life magazine. The lavishly illustrated feature, “The Old Crafts Find New Hands,” with photographs by Nina Leen, features an all-star revue of ACC Fellows and studio craft luminaries of the day. Peter Voulkos, Lenore Tawney, Harvey Littleton, Paul Evans, and others are shown at work, artfully posed, with their art displayed to its best advantage. The article trots out some chestnuts that we’d now interpret as outdated, characterizing the craft field as one that was once overlooked, but was finally (in 1966) in full flower. Parrott and her cohorts are presented not just as practitioners of particular art forms, but also in the classic postwar framework of a bohemian, hands-on, sun-dappled lifestyle. And of all those profiled, Parrott’s studio setting is the one that looks the most thoughtfully art-directed.

Parrott was born in Honolulu in 1929 to Japanese immigrant parents. She graduated from the University of Hawaii at Manoa in 1952 and went on to Cranbrook, where she studied with Marianne Strengell and Maija Grotell, and worked briefly winding warps by hand for Jack Lenor Larsen in New York City over one Christmas break. After graduating from Cranbrook in 1954, she began teaching at the University of New Mexico and was fascinated by the Navajo weaving and ceramic traditions she encountered in the Southwest. Perhaps retaining an attachment to the vibrant colors of her native Hawaii, she began weaving her own yarns and making her own dyes.

During her early career, Parrott was Zelig-like in her professional interactions with craft luminaries. She studied ceramics with Marguerite Wildenhain at Pond Farm in California, and met Sam Maloof through their shared participation in the 1964 World’s Fair. Maloof subsequently ordered wool shirts from Parrott, and used her fabrics to upholster his chairs. She was also adventurous: In 1959, a grant from the Tiffany Foundation enabled her to study on-site the weaving and dyeing traditions of Oaxaca, Mexico, and Quetzaltenango, Guatemala.

In the Canyon Road home she shared with her husband, Allen, and their sons, Ben and Tim, Parrott opened a shop for her work called the Market, where she sold clothing, blankets, and wall hangings. She undertook wonderfully eccentric commissions like the design and fabrication of wool ponchos for the ushers at the Santa Fe Opera, and weaving a tapestry version of the County Seal of Maui for the County Council Chamber in Wailuku, Hawaii. Her work was shown in an array of often medium-specific exhibitions, including “Modern American Wall Hangings” at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1962 – 63. She also had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) in 1963 and participated in the “Legends in Fiber” show at the Octagon Center for the Arts in 1986.

Even viewed through the tiny compositions of the ACC’s archival slides, Parrott’s vibrant palette and the fuzzy geometry of her weavings are irresistible. Though it’s impossible to say why Parrott isn’t currently better known – indeed, in coming years, she may earn posthumous acclaim – it could be by dint of her choice not to collaborate with industry, as some of her mentors like Larsen and Strengell did, or because her work wasn’t included in quite enough exhibitions to lodge her aesthetic point of view in the minds of critics. Parrott was also an artist who wove upholstery fabric and made clothing that people could (and did) wear. The practicality and utility of these creations may have led viewers and critics to view Parrott’s wall hangings differently than, say, the towering creations of Sheila Hicks, whose work is understood primarily as contemporary art.

As Parrott’s work resurfaces, it will be telling to see which fields find her work the most fascinating: fashion, weaving, upholstery, art – or, perhaps, all? The images from her World’s Fair photo shoot show relatively few finished products, but they document her practice and works in process in lush detail, open-ended, frozen in a moment before they could be categorized as one thing and not another. There is a sense of rich possibility in the choice to simply leave them there, with no modern-day hashtags or finding aids to tell a contemporary archive rummager just what they are discovering.

This article originally appeared in American Craft Inquiry.