Esprit de Corps

Esprit de Corps

Getting kicked out of not one, but two, schools in his native Paris helped Matthieu Cheminée find his métier just a little bit faster. Instead of heading straight to college at 18, he decamped to the home of his great-aunt, a painter in Taos, New Mexico, to learn English. Wandering the streets of the longtime artist colony, Cheminée found his people, and his passion. “

Right away, I started meeting all these incredible jewelers – both Native Americans and non-Native Americans – working in the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni styles. I spent hours sitting with them, watching their movements, and trying to repeat them,” recalls Cheminée, 48. “The first piece I made was a stamped silver bracelet, and that was it: I was hooked.”

As the planned one-year sojourn stretched to seven, Cheminée began to personalize his approach to stamping metal, which has remained a hallmark of his work. His gold and silver pieces have a refined rusticity, their heft and texture balanced by the intricacy of their patterns and his placement of gemstones. Just as important, he discovered an innate ability to bridge cultural divides with his open, gentle demeanor and mélange of curiosity, patience, and deep appreciation for traditional techniques.

Close to the end of his time in Taos, Cheminée met Sarah-Maya Côté Jirik, a Canadian woman moving to Mali to attend school. Cheminée planned to visit her for three weeks; he stayed for three years, embarking on a lifelong love affair with Côté Jirik, who became his wife, as well as with the jewelry and jewelers of West Africa.

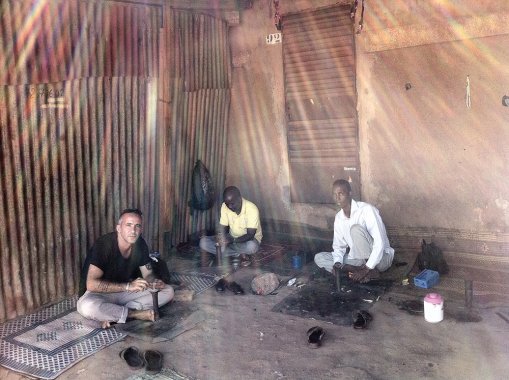

“When I first arrived in Mali, I was mesmerized and actually in shock – in a good way. I couldn’t speak for a few weeks. It almost felt like coming home,” explains Cheminée, who spoke the shared language of French with the people he met there. “I’d sit with Tuareg and Bambara artisans for months at a time, just watching and learning; and everyone was so unbelievably generous and giving with their knowledge.” Cheminée has reciprocated their generosity in many ways over the years, and his 2014 book, Legacy: Jewelry Techniques of West Africa, is like a love letter to the artisans of the region. An exhaustive compendium of tools, techniques, and materials, Legacy also profiles many of the jewelers who have become lifelong friends.

In 1998, the couple moved to Montreal, where they live with their 6-year-old son, Ziya. (Cheminée’s older son, Nemo, is 24.) Cheminée enrolled in the Ecole des Métiers du Sud-Ouest-de-Montréal, where he learned classical bench jewelry techniques. He has taught there and at the Ecole de Joaillerie, but has never lost his connection to West Africa, returning twice a year, on average.

When we caught up with Cheminée, he was about to depart for Guinea with his friend and publisher, Tim McCreight, a distinguished jeweler and author of The Complete Metalsmith, among other books. The two are travelling to help jump-start support for a jewelry school in Guinea and to discuss Cheminée’s next book, which is dedicated to stamping techniques in many parts of the world. Says McCreight, “Matthieu is unique for so many reasons: He shows respect for a number of ancient traditions, some of which he’s brought together in a really interesting way. But in addition to the beautiful work he makes and the books he creates, he’s also an extraordinarily kind and articulate teacher – he just has a huge generosity of spirit.”

Was there anything in your background that might have predicted your future relationship with jewelry?

Not really. But my dad was a volcanologist, and he used to travel around the world and bring back all these beautiful pieces for my mother – bracelets, pendants, and rings from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Peru, all over. I loved looking at the pieces and imagining where they came from.

Your connection to stamping metal dates from your early time in Taos, but you have taken the technique and made it your own. It has a very refined quality, for lack of a better word.

My stamping evolved from the Navajo approach, but for my work, it is a bit different. I make my own stamps, often from old chisels dating from the 1960s, and instead of making lines or a motif, I stamp an entire sheet of silver or gold in one direction with one or two stamps, and then I go back and fill every hole from the other direction to create a full texture. And I usually incorporate precious and semi-precious stones in one way or another.

I’ve seen the rather wonderful term “stampclastic” applied to your work. It’s a concise description of your hybrid approach: applying the anticlastic method of metal-shaping to your stamped sheets.

Exactly. I took an incredible class with Michael Good and learned his anticlastic technique of lifting up the metal on the sides, which makes the piece more comfortable to wear and gives it a more sculptural aspect.

You seem to approach people from so many perspectives – as a jeweler, as a fellow human, and in some ways as an anthropologist – documenting methods, techniques, and artisans throughout West Africa. What motivated you to write and photograph a book about it?

There is a writer I like very much, Amadou Hampâté Ba, who wrote, “When an old man dies, it’s like a library is burning.” When a jeweler dies, if he doesn’t have kids, or someone to carry on, he has no way to share his knowledge and techniques, and they, too, will just disappear.

Also, when I was first in Mali, I saw techniques that had almost vanished by the time I returned, for all kinds of reasons. In some cases, it was too labor-intensive or [there was a] civil war, Ebola – many different reasons. To me, that is a tragedy. I wanted to find a way to keep these traditions alive.

Your practice seems quite distinct from those you describe in your book.

I never incorporated the techniques that I learned in Africa. Later on, as a teacher, I did create workshops on specific African techniques, such as filigree and forging, in order to share the knowledge with my students and create some income for the jewelers, as I would split the money from the classes with the person who taught me the technique.

In almost every culture – whether it’s the Real Housewives of Beverly Hills or a village in India – jewelry is a potent signifier: of caste, social status, group identification, all sorts of things. Is this the case in the countries you have visited?

Absolutely, and in West Africa, many are also gris-gris pieces, worn for protection. It could have something written inside, to defend from illness, or to become richer, or fertile. You see even very young kids wearing a little necklace or a belt made of beads, to protect from diarrhea, for example. And the Fulani, in Mali, used to wear a lot of gold, because they had no bank accounts, but would wear all their net worth at weddings and other occasions to show status.

Is this still the case?

Well, you see less and less gold. And it’s been some time since I’ve visited the Fulani region, because of things like al-Qaida. There is also a lot of cheap jewelry flooding the market from China, and there is no way for these jewelers to compete with shiny pieces you buy for nothing.

In Legacy, you write about traditional Tuareg engravers, who are nimble at preserving time-honored techniques while also adapting to the shifting market. I would imagine that something such as tourist demand could have both positive and adverse effects.

The Tuareg are an interesting example. As a jewelry group in West Africa, they are the most famous, and their techniques are also very, very strong. The Tuareg really understood what was appealing to people and kept the most traditional parts of their jewelry without becoming frozen in time. I have a lot of Tuareg friends, and they find it easy to adapt to making more contemporary pieces without sacrificing their techniques. At the same time, they recognize the importance of continuity and how this also creates value for the tourists.

The Toolbox Initiative, which you founded in 2014 with Tim McCreight, connects tools donated in North America with practicing jewelers in West Africa. How did this begin?

When I was working on my book, I had a final technique I wanted to photograph in Senegal, and I invited Tim to join me. Before every trip, I always asked if anybody has extra pliers, saw blades, saw frames, and so forth, because it can really make a big difference to a jeweler over there. Tim and I realized the program could be much more effective on a bigger scale, so we created the Toolbox Initiative, with the idea of jewelers helping other jewelers. Companies such as Rio Grande Jewelry Supply have also been super-supportive. It’s really exploded.

When I spoke with Tim about the Toolbox Initiative, he described how Air France allows each traveler two 50-pound bags, so the two of you pack about 5 pounds of personal items, and the rest is all tools.

We have been lucky to get so many donations, but that creates a packing issue, which led us to create Toolbox Travel, where we bring a small group of jewelers from North America, who have an amazing opportunity to sit with the artisans and learn techniques such as filigree and forging and engraving firsthand. And, of course, [that] allows us to transport many, many more tools.

It’s amazing how resourceful these jewelers are, extracting the clay from termite mounds to create crucibles, for example, and forging anvils out of broken car axles.

Throughout West Africa, it’s an absolute necessity of a jeweler to know how to make things. And the Tuareg make some of the best tools I’ve ever seen. I’ve given hammers to Tuareg jewelers – sometimes not such great hammers – and I come back a few weeks later, and they’ve transformed them into this perfect, beautiful object. And then I’ve wanted it back!