The Glass Alchemist

The Glass Alchemist

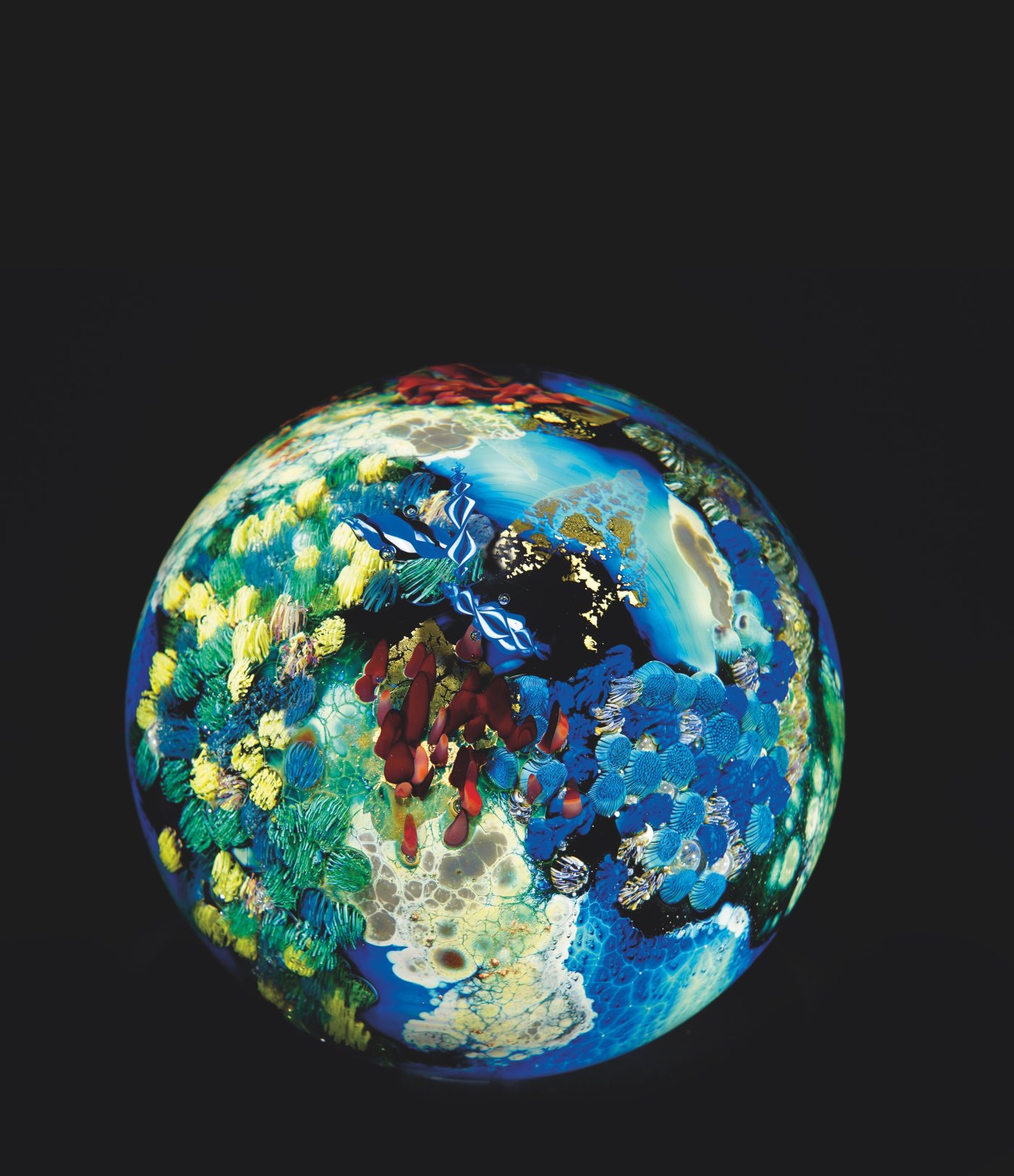

Josh Simpson’s Cerulean Megaplanet 1993, 5.25 in. diameter. Photo by Lewis Legbreaker.

It all started with a seemingly endless stream of eighth graders who swarmed his studio every Wednesday for the glass-blowing demonstrations he’d agreed to do. “They weren’t the least bit interested in me or goblets,” Simpson says. But who wasn’t astounded by the recent Apollo 8 mission photos of Earth rising behind the moon, like a little blue marble with white swirls? So, he says, “One day l decided to make a planet for them, just a simple clear glass sphere with a little blue world inside, to show the kids some of the mechanics of how glass is made, but also to give them something more to think about.”

His first little planets were a big hit. Moreover, Simpson had landed on a potent creative direction, one that would meld interests discovered in childhood with his adult propensity for experimentation with chemistry, materials, and technique. “Over time, the planets became larger and more complex,” says Simpson, a master of understatement.

Now, more than 50 years after the artist took his first gather of glass from a furnace he had built in 1971 with a fellow student at Goddard College, he recalls the events of an ordinary childhood that somehow led to his extraordinary present: Sitting on the back porch of his home in South Salem, New York, with his father, gazing at the moon and stars, pointing out constellations. Family trips to the Hayden Planetarium in the American Museum of Natural History, where he marveled at meteorites and a lunar panorama. Watching the fish tank in his bedroom, a self-contained water world between earth and sky. Mountains of sci-fi novels he “consumed” as a kid, he says. Talk of building a telescope, and attempting to grind a lens for one as an early experiment in glasswork.

Simpson’s first major success began one day while he was experimenting with melting silver on the surface of amethyst glass and—almost by chance—created a unique new kind of glass, a cerulean blue he called “New Mexico.” A client who’d purchased a set of New Mexico goblets told Simpson that “drinking out of them was like drinking from the sky.” Simpson marveled at “how something as utilitarian as a wine goblet could conceptually represent so much more.”

With the income from selling these hand-blown goblets, in 1976 Simpson purchased the farm outside Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, that would become his permanent studio. There, walking from his house to the barn almost every night to check on his glass furnaces, he is often inspired by thunderstorms, the night sky, falling meteors, or a rare aurora borealis.

Today, Simpson is revered as a pioneer in the studio-glass movement, having spent the past five decades inventing new color formulas and creating singular glass objects. Pieces in the Planets series are as small as marbles or as large as the 107-pound work from the Megaplanets series that resides at the Corning Museum of Glass. His platters, bowls, vases, “tektites,” “portals,” and other sculptural objects integrate his fascination with the astrophysical with ever more complex explorations into intricately layered colors, forms, and patterns.

One collector, smitten by Simpson’s paperweight-sized planets in a gallery 30 years ago, describes them as impressionistic. “They’re endlessly fascinating, a combination of serendipity and randomness and precision all in exquisite balance, and every time you look at them there’s something more to see.”

It is in my nature to experiment.

Josh Simpson

Josh Simpson at his home in western Massachusetts. Photo by Jamey Simpson.

The Art and Science of Invention

“It’s in my nature to experiment,” Simpson says. “I’ve invented new glass formulas and techniques that I use to make my planets more colorful and complex. Long ago, alone in the studio before I had any idea what I was doing, I worked with chemicals that could have poisoned me. Luckily, I survived! I wish I’d trained to be a glass chemist. At best I’m an alchemist, learning by experimenting with pure sand, minerals, and metallic oxides to make what I hope are new and exciting colors.”

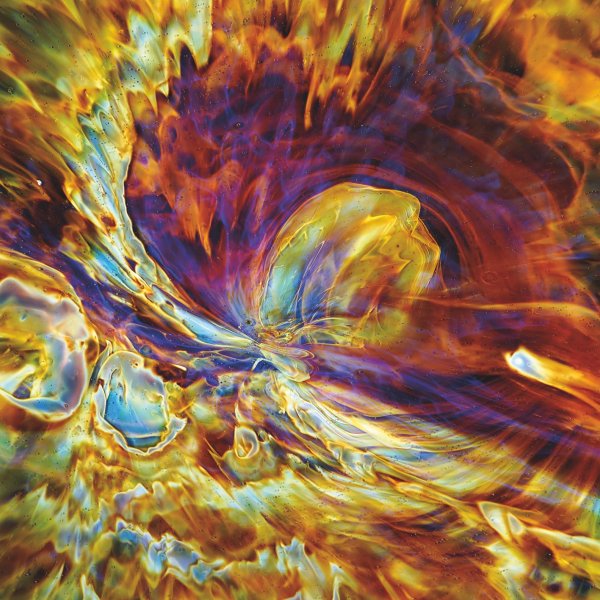

While creating one of his planets, Simpson interweaves his interests in the celestial, the natural earthly world, chemistry, and glassblowing techniques. The work is constantly evolving. Like Persian miniatures, the planets are intricately detailed and layered. Simpson begins with “a tiny gather of glass,” he explains, “and inside each sphere I often add a secret inner world that most people will never notice, but I know it’s there.”

He then incorporates self-taught Venetian techniques—murrine or millefiori (mosaic glass) and vetro a filigrana (filigree or glass canes)—within multiple layers of clear or dark silver glass, conjuring a multitude of otherworldly continents, flora, architecture, volcanoes, spaceships, mountain ranges, and satellites within each glass orb. He may also coat layers within the sphere with premade colored bits of glass, bringing texture and shape to the piece.

The artist spends most of his time at the furnace, where he builds each planet layer by layer; some pieces have as many as 20 layers integrating a plethora of elements. “All of my decisions are made through form and line and color and shading and depth; I want to lead a viewer’s eye as they explore and are drawn into the depths of each piece,” Simpson explains. “My goal is to pack each piece with as much detail as I can to make it as intriguing as possible, so you can’t let go.”

To generate singular hues and effects, he sometimes changes the temperature and oxygen flow in his furnaces. He might engrave the planets’ surfaces with a high-speed air turbine drill. “I also heat up the planets with different torches, including propane and oxygen acetylene, as those gases burn at different temperatures to make different color effects,” Simpson says. “I use a torch in the same way a painter uses a brush.”

Simpson at the glory hole in his studio with assistants Tucker Litchfield and Zak Grace. Photo by Jim Gipe Photo / Pivot Media.

Lynch first met Simpson 40 years ago at a craft fair, where she purchased an early planet. She’s also held events featuring work by Simpson and local artists. “These are teachable moments for talking about craft and the value of local art and artists,” she says, “after which everyone is inspired and passionate about craft.”

Simpson’s work is held in the collections of the Corning Museum of Glass, the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, and the Glass Museum in Lviv, Ukraine, among many others.

The spirit of Josh’s planets is encouraging people—whether in the arts or sciences—to consider what else there is to discover.

Cady Coleman

A planet at the North Pole. Photo courtesy of Josh Simpson, photographer unknown.

Good Chemistry

During the early craft shows in Rhinebeck, New York, Simpson would bring his small mobile furnace on a boat trailer for demonstrations. He’d also spend time with Carol Sedestrom (later Sedestrom Ross), and sometimes discuss craftspeople who were missing due to illness, injury, car breakdown, natural disaster, or housing dilemmas. In 1985, they decided to found the Craft Emergency Relief Fund (now CERF+), with Simpson as the fund’s first president. Since then, CERF+ has provided artists with more than $3 million in emergency relief grants. Simpson has also served as president of the Glass Art Society, and he has taught, exhibited, and been honored around the globe.

Simpson warms an interstellar disk in preparation for the final spin of the glass. Photos by Jim Gipe Photo / Pivot Media.

Simpson finishes a small corona interstellar disk with Litchfield and Grace. Photos by Jim Gipe Photo / Pivot Media.

THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

To find out more about how National Endowment for the Arts grants impact individuals and communities, visit www.arts.gov.

Additional support from the Windgate Charitable Foundation has made this article possible.

Learn even more about the artists shaping the future of craft by becoming a member of ACC today!

Support ACC, receive a subscription to the award-winning American Craft magazine, unlock travel discounts, and much more!