High Art

High Art

Micah Evans is used to receiving sideways glances. The 42-year-old glass artist has been a part of some of the most respected craft institutions in the country, from Penland School of Crafts to the Corning Museum of Glass, but the object he is most associated with is still, in some circles, taboo. Evans makes marijuana pipes, and his stock-in-trade hasn’t always endeared him to the more strait-laced members of his community.

“When I got the residency [at Penland in 2012], there were phone calls made to try to have me removed before I was even there. When I arrived, there were more phone calls, explaining that I had turned my studio into a head shop and was selling bongs to students,” Evans says, chuckling. “And this was actually before I was even allowed in my studio.”

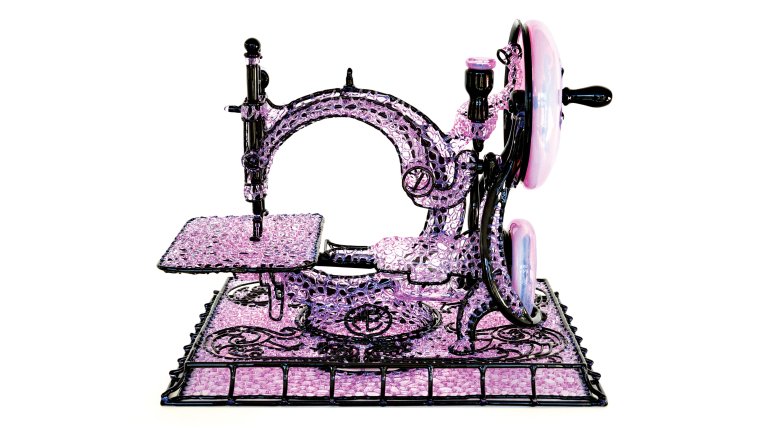

It was no surprise to Penland’s officials that their new artist-in-residence made drug paraphernalia; “they had Google,” he points out. But his pipes stand up to scrutiny, combining structural sophistication with bold flourishes and striking colors. They look, at times, like compact mazes, full of compartments and channels and trap doors. They fold and bend in on themselves, leaving user and observer alike to wonder how they work.

Evans, who now lives in Austin, Texas, also makes sculpture; the thin, connected strands of glass can evoke neural pathways. But he considers his functional work equally important. “I treat that pipe with sincerity,” he says. “I treat it as a craft object. I treat it very seriously.” That devotion has helped him break down preconceptions in the craft community. “When I would be in a situation where someone would chuckle or laugh or assume [a pipe was] a novelty, I would approach that conversation with language that would immediately disarm that. And the next thing I know, I would have a 60-year-old weaver with a pipe in her hand, fascinated with the object.”

Evans’ own fascination began recreationally; he used his share of pipes before fashioning his first one at Stone Way Glass in Seattle, a pipe shop where he hung around and eventually worked. He and some friends later moved to Jacksonville, Florida, and opened their own studio on a whim. That’s where his skills developed more fully. “In order to keep the doors open, I kind of had to say yes to any project that came through the door,” he says. In the mid-2000s, Evans moved to Miami to work with ACC Fellow William Carlson at the University of Miami, who taught him both how to cast and how to balance the various elements of the making life. “I got to see how a successful glass artist approached the business side . . . how he worked through the stagnant times that you often hit as an artist.”

Evans’ sculpture helped lead to the Penland residency and a teaching position at Corning, among other accomplishments, while his functional pieces help pay the bills. (Evans estimates that 70 percent of his income comes from functional wares; “I try to keep money out of the fine art side,” he says.) In recent years, his work in what he calls “niche vice markets” has expanded to include high-end liquor bottles and decanters. Like his pipes, these are the product of an attentive eye and a keen scientific mind, and sometimes include features such as aeration systems. He sells his pipes and bottles at shows across the country, which he advertises on his popular social media accounts.

Evans predicts that the pipe-making industry will only grow as marijuana use continues its move into mainstream (and legal) society. “As the political nature of the pipe changes, as is happening pretty rapidly, there are opportunities to present it not in the typical head-shop scenario, the way people normally would come across one of these objects,” he says. “There’s a different generation of people that no longer think it’s taboo.” This cultural shift dovetails nicely with Evans’ own transition from a hard-partying, country-crossing twentysomething to a more settled adult. “I have the same relationship with liquor as I do with marijuana,” he says, “in that it complements my lifestyle from time to time; it no longer is my lifestyle.”

These days, Evans speaks with the easy tone of someone with few regrets or what-ifs. And no wonder: He has followed his passions, unconcerned with appearances and unafraid of mistakes. Even now, as an accomplished and in-demand maker, he looks back on his beginning years with fondness. “It was fun,” he says. “I learned to float on a surfboard and I started my first glass studio. That was an extremely valuable experience, starting your own thing, trying to figure out how to make ends meet.”