Hiromi Takizawa

Hiromi Takizawa

When Hiromi Takizawa came to the United States from Japan as a 22-year-old, her primary goal was linguistic. “I grew up in a tiny town, where we had one foreigner,” she says. “I was always so curious about learning English.” She decided the best way to learn was to enroll in a language course at Santa Ana College in Southern California.

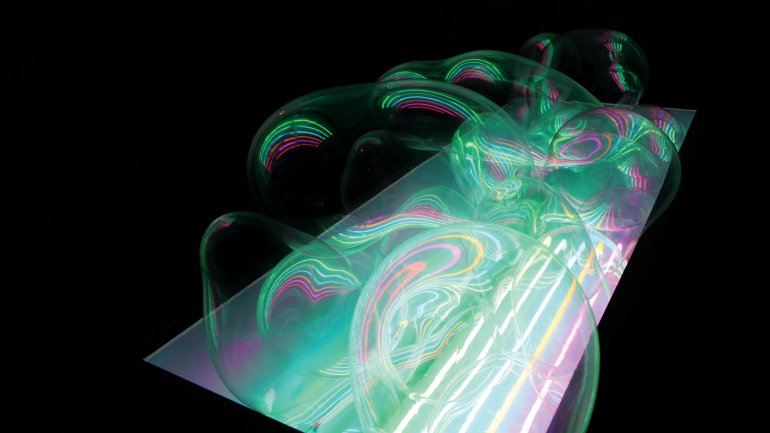

A chance visit to the school’s glassblowing studio, though, would soon provide her a different kind of fluency. “I was immediately drawn to the fluidity of the material – it’s always moving when it’s hot, so it’s very challenging. I also like the optics it creates – transparent, reflective, refractive,” says Takizawa, now 39. “At the time, I had such a sense of longing for my family and the place I’d grown up, but I couldn’t talk about that in English, so I worked through it visually, through the language of glass.” She soon developed an evocative, atmospheric lexicon of glass, light, and interior and exterior spaces. She used her material’s properties to explore her own history.

Takizawa went on to earn an MA in glass at California State University, Fullerton, and an MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University, winning scholarships and exhibition invitations along the way. And while Takizawa’s English is now fluent and the US is home, she continues to communicate through her medium. In her 2007 piece Crossing the Pacific Ocean, a blue neon silhouette of a plane hangs over an ocean of glass bubbles, each reflecting the plane outline, speaking to both distance and tranquility. For Ultraviolet, an ingenious storefront light installation she created in 2013, she assembled a “box of curiosities” using neon lights and plants that could be viewed from inside and out. The plants recall the lush foliage of her youth, while the colors evoke a California sunset. “A lot of my work is exploring cultural differences in a positive way,” Takizawa says, “but also still with a sense of longing for where my family is and where I grew up.”

In 2015, Takizawa returned to Fullerton as an assistant professor and coordinator of the glass program, a job that now consumes much of her time. She is credited with securing a $300,000 grant to modernize the school’s aging glass studio and launch a visiting artist’s program, and she is developing a new curriculum. The position is not without trade-offs, though. “I’m very grateful for the opportunity for a teaching job, and I love working with a new generation. But it’s taking a lot of time from my own practice,” Takizawa explains. “The last two years I did a lot of experimenting but never fully finished work.”

She is, however, working on more public projects, and for those she’s collaborating with her husband, woodworker and mixed-media artist Elijah Wooldridge. They’re currently creating the site-specific California Natives, which consists of five 5- to 7-foot laser-cut stainless steel leaves that will be installed this summer at a new mixed-use development in Santa Ana.

Takizawa gravitates toward public art because she can reach a wider audience. “I love for my work to be seen by everyone, from little kids to Grandpa and Grandma,” she says. “I don’t think my work fits into a fancy gallery.”

In the end, what makes Takizawa an accomplished educator is also what sets her apart as an artist: her unremitting love for her work. Even as she pivots to stainless steel with California Natives, she continues to experiment with light and reflection: Each leaf will be painted a different color to create a bit of optical engineering. “When someone walks around it, the colors change, so there’s a sense of warmth and changing seasons,” she says. “So, actually, it will have the quality of glass.”

Here and There

Sister, sister: Takizawa has an identical twin sister in Japan who teaches kindergarten. “Twins are very interesting,” she says. “Not like a brother or sister, but like a clone.”

Parental guidance: When Takizawa led a glass workshop in Japan in 2017, her parents got to see her in the studio for the first time. “I was totally nervous,” she says, “but it was great they finally got to really know what I do, see how the material moves, and how the team works.”

What’s next: Takizawa is experimenting with giving glass form to moss and lichen and collecting sounds from birds and humans “to create a visual map of sounds in glass.”