Honoring Accomplishments

Honoring Accomplishments

↑ The 2020 recipient of our Gold Medal for Consummate Craftsmanship, Joyce J. Scott is a multifaceted visual and performance artist best known for her work in jewelry, beadwork, and glass.

Photo: Justin T. Gellerson, the New York Times, Redux

While so much is on pause in 2020, people across the country continue to practice their crafts. Indeed, craft offers much to culture and to our lives at this time, reminding us of the importance of slowing down, reconnecting to the creative spirit, transforming raw materials into objects with beauty and meaning, and experiencing the satisfaction that comes with making things with your own hands.

So, this year it is especially meaningful to us here at the American Craft Council – the nonprofit publisher of American Craft – to honor individuals and organizations for exceptional artistic, scholarly, and philanthropic contributions to the craft field. We are delighted to introduce you to the winners of the 2020 American Craft Council Awards.

With this award, five accomplished makers enter the ACC’s College of Fellows, which honors those who have demonstrated outstanding achievement in the field of craft for more than 25 years. These new members have been elected by their peers and other leaders in craft.

We also celebrate the Gold Medalist for Consummate Craftsmanship, a career-crowning honor reserved for a previously elected Fellow; an Honorary Fellow for scholarship; the winner of the Aileen Osborn Webb Award for Philanthropy; and the Award of Distinction, which goes to a craft museum this year.

We invite you to cozy up, make some tea, and fill your cup with inspiration as you meet this year’s awardees.

~The Editors

Jump to:

Joyce J. Scott | Annabeth Rosen | Bob Trotman | Sonya Clark | Lisa Gralnick | Katherine Gray | Patricia Malarcher | Barbara Waldman | Fuller Craft Museum

Joyce J. Scott

Gold Medal for Consummate Craftsmanship

Joyce J. Scott was born to make art. “People ask me how I started as an artist, and I tell them: ‘In utero. I came out of my mother’s womb. I had a little beret hat on. I was waving. I said to the doctor, ‘Move, you’re in my light.’ I think I had a cigarette and a martini, and I was ready,’” says Scott, this year’s recipient of the American Craft Council’s Gold Medal for Consummate Craftsmanship. “I don’t think I had a choice. My direction – my avatar, my point, that horizon – always had art splayed all over it.”

↑ Joyce J. Scott

Portrait: Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery

↑ Blue Baby Book Redux, 2018, beads, thread, 3 x 4.25 ft.

Photo: Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery

Scott, a 2016 MacArthur grantee, is a mixed-media visual and performance artist best known for figurative sculpture and jewelry made using free-form, off-loom bead-weaving techniques similar to the peyote stitch and its variations, as well as blown glass and found objects. She learned beadwork at age 5 from her mother, well-known art quilter Elizabeth Talford Scott, whom Scott refers to as “my first mentor.” “She created an environment that was very festive – always using her stitchery to make the house look better,” Scott says.

↑ Excessive Force, 2018, beads, thread, found objects, 3 x .75 x .75 in. ea. (bullets), 3.5 x 3.25. x 1.25 in. (butterfly)

Photo: Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery

Scott’s parents were sharecroppers in North and South Carolina before they moved to Baltimore in the 1940s “to achieve a better life and not be eye to eye with the kind of overt racism that tracked you every moment of your life,” says Scott, who also calls Baltimore home. But racism didn’t disappear when they moved north. It simply took on a different shape, and her parents still experienced the limits of being Black in America. “My parents were upset because they didn’t have the ability to have an academic education, and then I came, and I was hungry for education,” she says. “They supported me in that. I had no reason to be anything other than what I wanted to be.”

And what Scott wanted to be was an artist. “I saw no other way to completely be Joyce. I saw no other realm that would allow me the freedom and the voice that I have.”

She earned a BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 1970 and an MFA from the Instituto Allende in Mexico in 1971. She learned the peyote stitch, or diagonal weaving, from a Native American student at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine in 1976, and it became central to her beadwork. Scott’s oeuvre blurs lines between the materials often associated with “craft” and those associated with “fine art,” and it crosses styles and mediums, from jewelry to large-scale outdoor installations.

↑ Aloft, 2016 – 17, handblown Murano glass, wood, beads, mortar, thread, 3 x 1 x 1 ft.

Photo: Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery

And what Scott wanted to be was an artist. “I saw no other way to completely be Joyce. I saw no other realm that would allow me the freedom and the voice that I have.”

She earned a BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 1970 and an MFA from the Instituto Allende in Mexico in 1971. She learned the peyote stitch, or diagonal weaving, from a Native American student at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine in 1976, and it became central to her beadwork. Scott’s oeuvre blurs lines between the materials often associated with “craft” and those associated with “fine art,” and it crosses styles and mediums, from jewelry to large-scale outdoor installations.

↑ Sex Traffic 2, 2017, blown glass, metal, glass beads, thread, wire, 10.5 x 31.5 x 8 in.

Photo: Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery

During the past 50 years, she’s been prolific – a fact that has become even more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic. “I’m 72 now, so there’s no way I’m leaving my house. I’ve just been making things – sculpture, jewelry, a teapot. I’m making a big red monkey,” she says with a laugh. “I’m like the little boy in that movie Home Alone. I’m wandering around, getting into trouble in my own house.”

Scott won the MacArthur at age 68, and she considers it a monumental moment – in large part because of where she was in her career. “People generally get the MacArthur when they are younger, not this age. It really is money that says, ‘We are investing in your career, in your future, in what you may become,’” she says. So, to have the Fellowship committee acknowledge her future work “really buoyed me and made a difference.”

As an African American and a feminist, Scott confronts difficult themes in her pieces, including race, misogyny, sexuality, stereotypes, gender in-equality, social disturbance, economic disparities, history, politics, rape, and discrimination. With this work, she aims to make a difference in the world. “I’d like my art to induce people to stop raping, torturing, and shooting each other,” she says. “I don’t have the ability to end violence, racism, and sexism, but my art can help people look and think.”

↑ Harriet’s Rifle 2, 2018, blown glass, beads, thread, repurposed objects, 1 x 3.75 x .5 ft.

Photo: Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery

“I don’t think I had a choice. My direction – my avatar, my point, that horizon – always had art splayed all over it,” says Joyce J. Scott of her path.

Harriet’s Quilt, 2016 – 17, plastic and glass beads, yarn, knotted fabric by Elizabeth Talford Scott, found trunk, 2.5 x 3.75 x 2 ft.

Photo: Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery →

↑ Araminta with Rifle and Vévé, 2017, painted milled foam, found objects, blown glass, mixed-media appliqués, beaded staff

Photo: Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery

Annabeth Rosen

Fellow

What inspires ceramic sculptor Annabeth Rosen? A better question might be, What doesn’t? “I get excited about a lot of things, and I don’t choose,” she says. “That’s one of the privileges of being an artist. Whatever I’m excited about, I can use, I can embrace.”

Rosen received her BFA from New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University in 1978 and her MFA in 1981 from Cranbrook Academy of Art, where she learned how to draw inspiration from the world around her from a famous mentor: ceramic artist Jun Kaneko, ACC’s 2018 Gold Medalist.

↑ Annabeth Rosen

Portrait: Courtesy of Annabeth Rosen

↑ Droove, 2012, fired ceramic, rubber inner tube, 13 x 16 x 20 in.

Photo: Lee Fatherree

“Something I learned from Jun, which I’ve thought about my whole life, is that anything – everything – can be useful,” says Rosen, 63, who has served as the Robert Arneson endowed chair in the department of art and art history at the University of California, Davis since 1997. “Since you can only choose from what you have access to, your obligation as an artist is to have expanding and deepening resources.”

Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, Rosen took her first ceramics class at the Brooklyn Museum as a teenager. From then on, “I just never stopped working in clay,” she says. “I just worked every day, and now 40 years have passed, and I am still working.”

Rosen’s work is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Oakland Museum of California; the Denver Art Museum; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; and in many public and private collections. She has received two National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, a 2018 Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Pew fellowship, and she was named a United States Artists Fellow in 2016.

In the studio, she continues to explore new ways of working, such as integrating rolled pieces of paintings into her ceramic sculptures or flattening ceramic pieces and drawing on them. “Both practices are giving way to each other and becoming the same,” says Rosen. And, true to her nature, she adds, “I’m really excited about it.”

↑ Bunny, 2011, fired ceramic, steel baling wire, steel armature, 2-inch casters, 3.75 x 2.5 x 2 ft.

Photo: Lee Fatherree

↑ Untitled (#100), 2005 – 06, fired ceramic, steel baling wire, 18 x 19 x 19 in.

Photo: Lee Fatherree

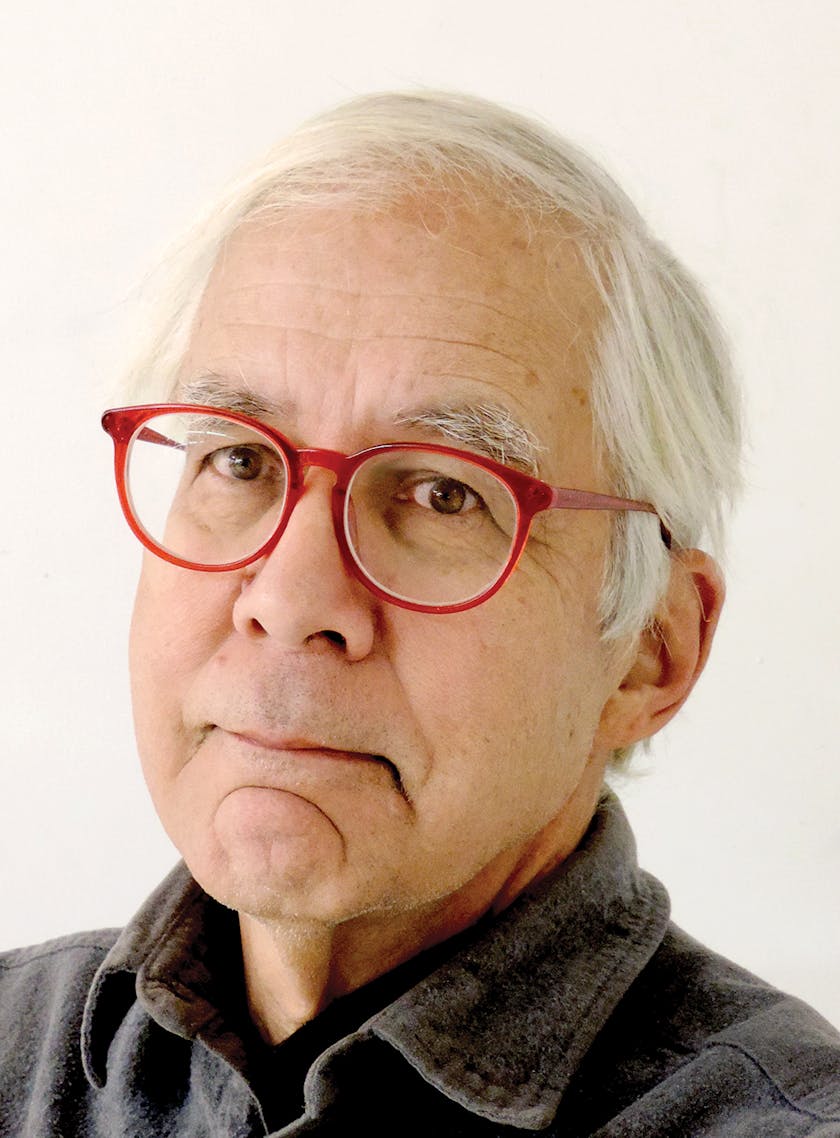

Bob Trotman

Fellow

Before Bob Trotman was a craftsperson and a wood artist, he tried out being a schoolteacher and a poet. Then, in 1973, he and his wife, Jane, spent the summer living and helping out at a commune in western North Carolina, where he was asked to be the community’s carpenter. He’d received his BA in philosophy from Washington and Lee University, but nonetheless dove into carpentry willingly, relying on knowledge he had from an eighth-grade shop class – which wasn’t much. “I started with an ax and a two-man crosscut saw, went out into the woods, and cut some trees down,” says Trotman, 73. “It was green wood, and I didn’t know it would split all to pieces. But it was free, and it was big, and it was exciting.” And it’s how he discovered his true path.

↑ Bob Trotman

Portrait: Courtesy of Bob Trotman

↑ Floorman, 2011 and 2016, carved wood, paint, wax, 2.25 x 6 x 2.75 ft.

Photo: David Ramsey

In such handwork, Trotman found something he’d missed in other professions. “I enjoyed working alone and feeling the flow of having something start off as an idea in my own mind, and then, gradually, seeing it exist in the real world. It’s a kind of satisfaction I’d never felt before in teaching English or in trying to write poetry.”

Later that year, he discovered the Foxfire books, a series of manuals “that had to do with the old mountain ways of doing things,” he says. Through them, he gathered valuable knowledge and got better at cutting legs, drilling holes, and making stools and tables out of slabs of wood. When he learned a few years later that Penland School of Craft was just 50 miles from the farm, he started attending classes there, studying with such renowned woodworkers as Jon Brooks and Sam Maloof.

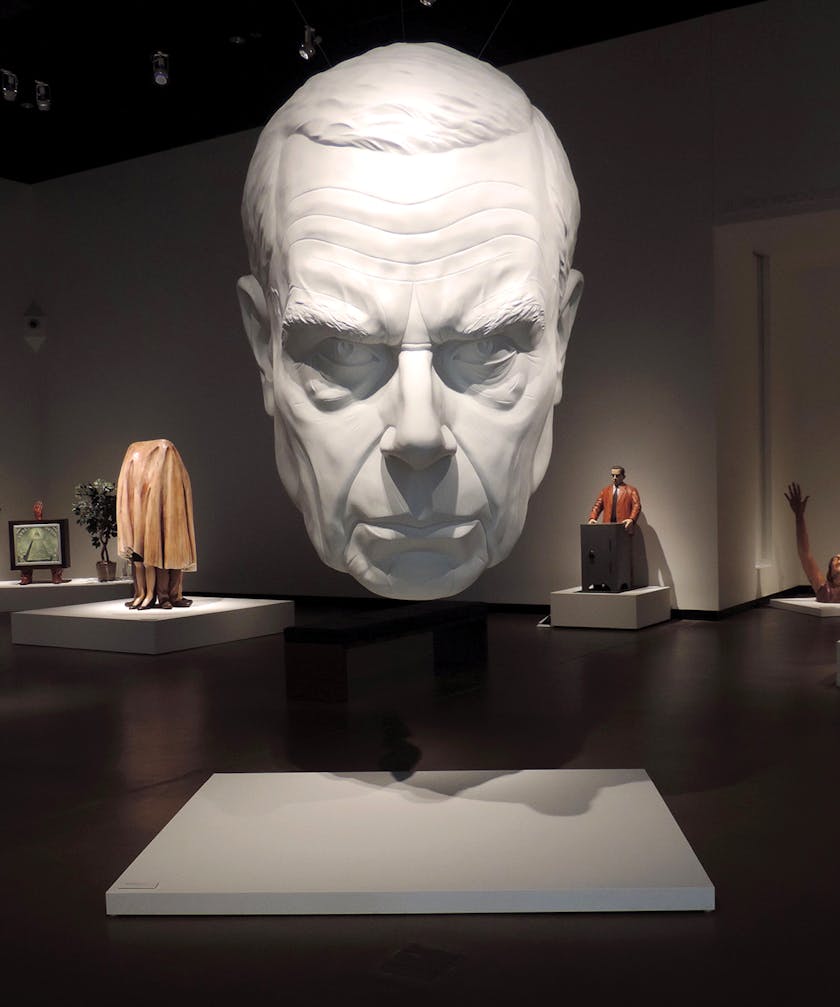

↑ Face Time, 2017, fiberglass, bondo, paint, 6 x 4.75 x 4.5 ft.

Photo: Bob Trotman

Early in his career, Trotman focused on making functional work, which was well received. “One of my pieces was on the cover of Architectural Digest, which I consider something,” he says. But in the ’90s, he began to make sculpture as well, sometimes combining it with furniture. His 1994 work White Guy, for example, depicts “a guy in a business suit looking kind of depressed with drawers coming out of him in various places.”

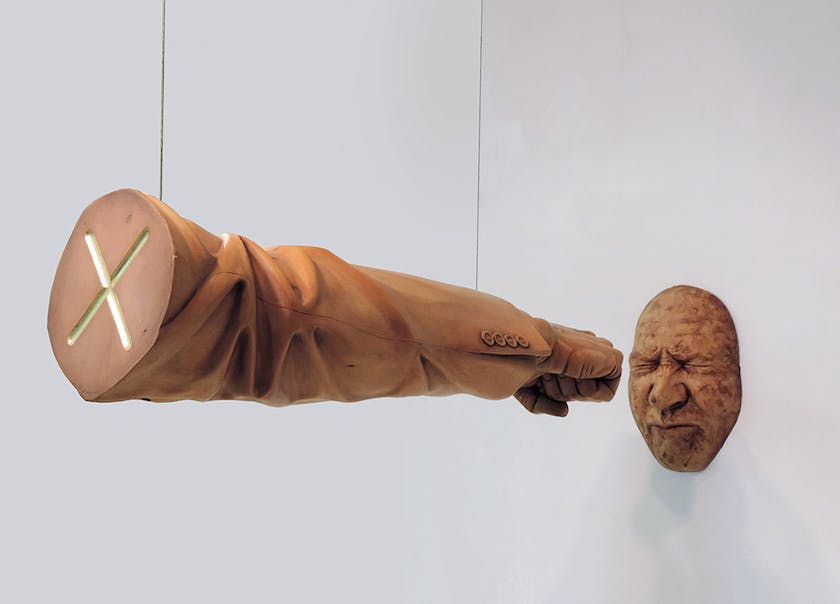

↑ Have a Nice Day (2019) has a motorized fist that humorously pulls back and forth to hit the silicone rubber face.

Photo: Bob Trotman

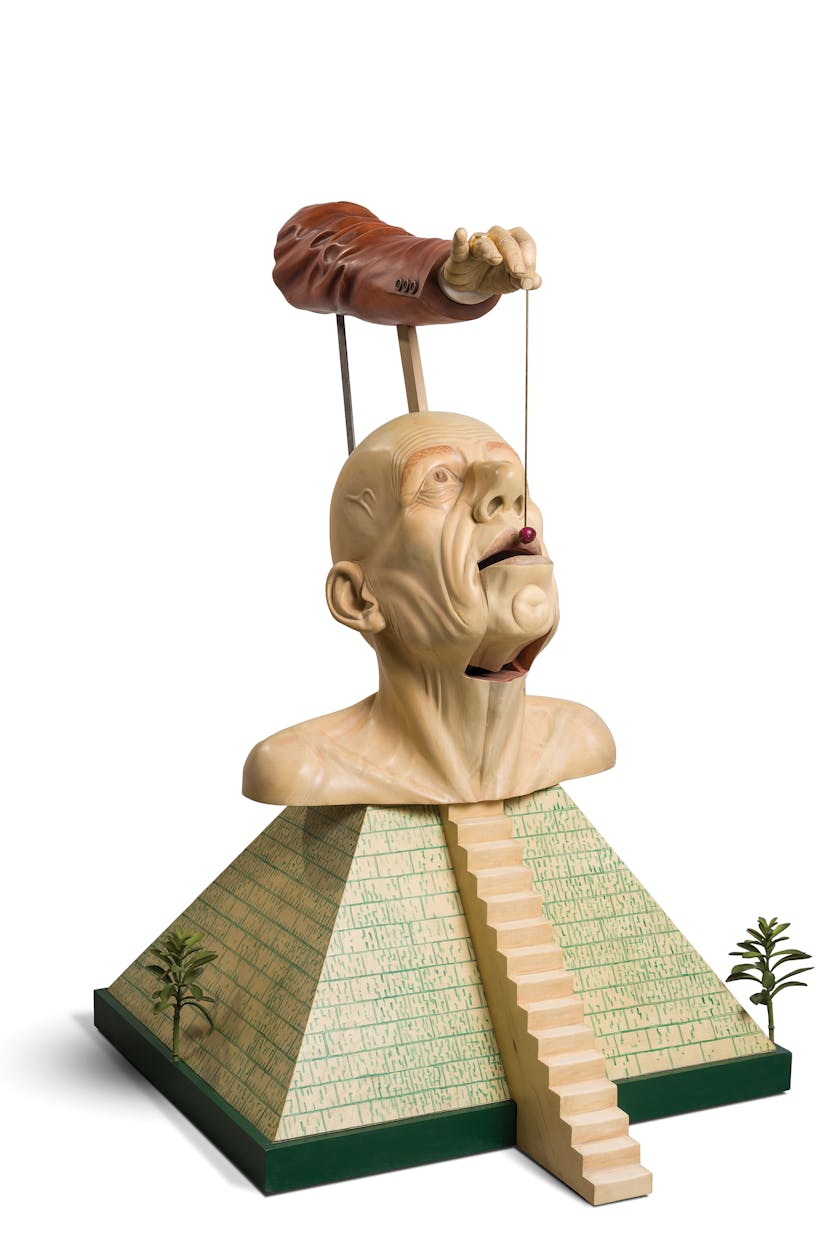

Since 1997, Trotman’s work has been purely sculptural, sometimes kinetic, and often with a strong point of view. He sees his contemporary work in relationship to 19th-century “show figures” – the figureheads on ships – and carved Gothic figures, but he hopes his pieces do more than harken the past. As with his traveling exhibition “Business as Usual,” he satirizes the power, privilege, and pretense “that secretly, or not so secretly, shape the world we live in.”

↑ Denier, a 2016 kinetic sculpture that stands 5 feet tall, moves an artificial cherry in and out of the mouth of its figure.

Photo: David Ramsey

Sonya Clark

Fellow

For Sonya Clark, craft is a connector. “Wherever I go, I can find a craftsperson, and even if I don’t share a language with that person, we still have a way of working together,” she says. When she was in Dakar, Senegal, last year for the Black Rock Residency founded by Kehinde Wiley, she met a fisherman named Souleyman Diop at the seaside and ended up netting beside him to learn his technique. “Netting, for him, is a tool, and for me, it’s a textile art, but the thing that connects us both is that it is a craft. We had the language of craft between us.”

↑ Sonya Clark

Portrait: Diego Valdez

↑ Writer Type, 2016, typewriter, human hair, 7 x 10 x 11 in.

Photo: Taylor Dabney

The celebrated textile artist, who has often used hair in her work, also shared the language of craft with her tailor grandmother, who taught her how to sew, as well as with her childhood neighbors, a family from the West African country of Dahomey (now the Republic of Benin), whose daughters would often do Clark’s and her sister’s hair. It got her “interested in how hair signifies culture, race, economics – all sorts of things – and the power instilled in hair.”

Craft’s ability to bridge generations and cultures is what gives it potency, she says. “To effect change, it helps to use a medium and a language that has deep roots and can branch across many people and cultures. In that way, the familiarity of craft, the familiarity of crafted objects, the familiarity of materials that we associate with craft, the depth and the roots of the medium and the history of craft itself, is its power.”

Clark’s 2019 exhibition, “Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know,” made in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, asked what would happen if the Truce Flag, the dishcloth waved to end the American Civil War and a symbol of peace, replaced the Confederate battle flag as a cultural signifier.

The multi-floor “Monumental Cloth” exhibition involved installation, performance, and participatory elements, including the opportunity to help weave a Truce Flag.

Flag photo: Carlos Avendano / Weaving photo: Jessica Kourkounis

Clark, 53, has a BA in psychology from Amherst College (1989), a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (1993), and an MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art (1995), where she was awarded its first-ever Distinguished Alumni Award. She is a professor of art at Amherst College, from which she received an honorary doctorate in 2015, and is the recipient of several awards, including a United States Artists Fellowship, a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant, an 1858 Prize, and an Anonymous Was a Woman Award, among others.

Her parents – a psychiatrist and a nurse – “thought I would become a mathematician or do something with engineering,” says Clark. But once she was at SAIC with teachers like Nick Cave, her course was set. “I felt like I had oxygen in my lungs, like I was finally using the full capacity of my lungs,” she says.

↑ These days. This Country. This History. 2019, unwoven and rewoven commercially printed US and Confederate Battle flags, 10 x 7 in.

Photo: Sonya Clark

Lisa Gralnick

Fellow

Lisa Gralnick, a metalsmith and art professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, isn’t happy unless she’s being challenged, both technically and conceptually. “Once something becomes second nature to me, I’m not interested in it anymore,” she says. “It’s one of the reasons I’ve gone through so many different bodies of work in my career. I’m not too interested in being defined by something as pedestrian as style.” She’d rather see herself as a problem solver.

↑ Lisa Gralnick

Portrait: Jim Escalante

↑ Gold Standard Part I: # 19 (Revolver), 2010, 18k gold, plaster, acrylic mount, 7 x 8 x 14 in.

Photo: Jim Escalante

As a graduate student at SUNY New Paltz in the late-1970s, Gralnick worked primarily in precious metals and enamel. For the first couple of years of her art career, she created and sold jewelry at major craft fairs. “People were buying this work, but I was feeling disenchanted,” says Gralnick, 64. “I was feeling as though people were buying it because of the precious materials and their inherent beauty and that whatever I had to say conceptually was getting lost.”

In 1985, an accident led to Gralnick’s next phase: working with black acrylic. She was playing a Wagner opera on vinyl when something fell off the wall, hitting and shattering the record. She started gluing the pieces together, “and that led me to a whole body of work.”

After that, Gralnick didn’t think she’d return to precious metals, but after seeing a 1987 Jannis Kounellis exhibit in which he’d gold-leafed an entire wall, she found herself thinking about the history of gold as both a commodity and as an element that is stolen, pillaged, recycled, and revered. It inspired a gradual return to working with precious metals, resulting in a diverse array of work: mechanical jewelry (her Anti-Gravity series), reliquary necklaces incorporating found objects, brooches of almost paper-thin gold, and her conceptually driven Gold Standard series.

↑ Gold Standard Part III: Halo, Probably 14th Century, 2008, recycled gold, enamel, acrylic, glass, 11 x 15 x 14 in.

Photo: Jim Escalante

Gralnick was a rebellious teenager in the 1960s and early ’70s, and although she’d been a good student, her parents worried they were losing her. “So they signed me up for a Saturday jewelry class that I took with my father at a local art center. They hoped it would straighten me out a little,” says Gralnick, who since that time has received two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation grant, and numerous awards from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “What they didn’t bargain for was that this jewelry class would change my life.”

↑ Scene of the Crime, 2018, oversized jewelry: brass, ceramic, silver, pearls, glass gemstones, enamel; jewelry box: wood, pink Naugahyde, velvet, brass, 8 x 4 x 4 ft.

Photo: Jim Escalante

Katherine Gray

Fellow

When learning new things, Katherine Gray tends to catch on quickly. But that wasn’t the case with glassblowing; the physical challenge is what drew her to it. “It’s almost like a dare to go into the studio and gather glass out of the furnace and make something out of it,” says Gray, a glass artist and professor of art and design at California State University, San Bernardino. “A lot of other things came too easily to me, so I really appreciated how challenging it was to work with glass.”

↑ Katherine Gray

Portrait: Fredrik Nilsen

↑ Iridescent Aura Diptych II, 2018, blown glass with iridescent coating, steel frame, 20 x 20 x 3 in. ea.

Photo: Andrew K. Thompson

Gray, 55, started working in glass in 1985 as an undergraduate at Ontario College of Art in Toronto. At the time, she had a vague notion that she wanted to be a furniture and lighting designer. But that changed when she walked into the campus glassblowing studio. “I kept taking glass classes all through undergraduate,” she says, “then ended up going to grad school. At that point, I knew glass was my destiny.”

For Gray, part of the appeal of glass is its inherent, often hard to reconcile, qualities as a material. “There is nothing else like glass that is molten and transparent and brittle and strong and fluid and solid and just all of these contradictions incarnate,” she says. “I found a lot of metaphors in that that I felt were rich and ready to be exploited.”

Gray received her MFA in glass from Rhode Island School of Design in 1991. Her work has been exhibited at galleries across the country including, most recently, in solo shows at Craft Contemporary in Los Angeles and the Toledo Museum of Art. She’s also a resident evaluator on the Netflix show Blown Away, a competition in glass art.

↑ As Clear as the Experience, Redux, 2019, blown glass, steel, plate glass, 5 x 3 x 1.25 ft.

Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

↑ Forest Glass, 2009, as installed at the Corning Museum of Glass, pre-existing glass, acrylic and steel shelving, 9.5 x 5.25 x 2.5 ft. (tallest tree)

Photo: Courtesy of the Corning Museum of Glass

As time has gone by and technology has evolved, Gray’s dedication to the craft of glassblowing has only gotten stronger. “With the rise of computers and simulated experiences, there’s something about working with your hands – and working with glass, in particular – where you have to be absolutely focused and in the moment with the material,” she says. “There’s no taking a break or checking some text messages or anything like that. It’s an increasingly rare experience.”

↑ Tabletopiaries, 2007, blown glass, 17 – 23 in. tall ea.

Photo: PJ Cybulski

Patricia Malarcher

Honorary Fellow

When writer and artist Patricia Malarcher went to graduate school for art, she asked her design teacher, the painter Kenneth Noland, for some recommended reading. “I said, ‘Would you recommend a book?’ And he said, ‘There is no book.’” It was a big shock to someone who had always learned from books and words. “I just felt like I had fallen off a cliff,” she says.

Malarcher started her career in the early 1950s as an assistant editor for a magazine, so words were a big part of how she understood the world. She’d always wanted to study art, however, and she didn’t want to wait until she retired to do so. So, in 1954 she entered graduate school, receiving an MFA from the Catholic University of America, where she studied painting.

↑ Patricia Malarcher

Portrait: Rhoda Sidney

In 1957, when her ceramics professor encouraged a visit to an exhibition of wall hangings at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, Malarcher found her true artistic passion: textiles. “When I saw them, I felt I was in love with them and that I could probably take everything I had learned about color and composition and transfer it into fabric,” she says.

↑ A sampling of Surface Design Journal issues edited by Patricia Malarcher.

In the 1960s, she completed several stitched and appliquéd liturgical commissions, and in the following decade had her work featured in solo and group exhibitions. But after reading the book Centering: In Pottery, Poetry, and the Person by M.C. Richards, Malarcher felt a calling to connect her passions for words and handwork. In 1976, she started writing reviews for Craft Horizons and, a few years later, for Fiber Arts. She covered regional craft news for the New York Times in the 1980s and ’90s and also did about six years of doctoral work at New York University. As a 1989 Renwick Fellow, Malacher studied why craft has been historically misunderstood, disrespected, and ignored by fine art circles – something that in recent years has changed as galleries and museums increasingly recognize “craft” as “art.” Then, from 1993 to 2012, she served as editor of Surface Design Journal.

Malarcher insists that she never had a master plan for her career. Instead, she set one goal at a time, following both her inner “knowing” and serendipitous opportunities. “In the beginning, I was really moving along quite well in my journalistic career, but then I felt I really wanted to – I just felt driven to – make art part of my life. And I’ve insistently kept with that ever since, no matter what else I did in addition.”

Barbara Waldman

Aileen Osborn Webb Award for Philanthropy

I think it is just miraculous what artists create,” says Barbara Waldman, a passionate advocate for craft and design, who claims to have no creative talents of her own. “I was a gift wrapper at a men’s store in high school,” she says. “I still enjoy wrapping gifts, but that’s about it for making things.”

No matter. Waldman may not see herself as creative, but her volunteer efforts at craft organizations across the county have helped support many in this creative field.

↑ Barbara Waldman

Portrait: Courtesy of Barbara Waldman

A past American Craft Council board chair and now a Life Trustee, Waldman has held leadership positions on the boards of many craft organizations across the country, including the Museum of Craft and Design in San Francisco; the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City; the international organization Art Jewelry Forum; the Founders’ Circle, a support group for the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina; and the James Renwick Alliance, a support group for the Renwick Gallery at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC.

Waldman discovered art in a meaningful way as a college student in the late 1960s, and although it never became her major, she did land a job in the art history department running the slide projector. “It was fabulous because I was able to observe all the lectures, but I didn’t have to take any tests,” she says. Then, in the early 1970s, Waldman visited her first art fair – the Old Town Craft Fair – in Chicago. “I bought my first necklace there and my first ceramic sculpture,” she says. The experience lit a spark in her that resulted in a serious love for art fairs. “I kind of became a craft show groupie.”

After many years in the corporate world and the launch of her own marketing business for designers and architects, Waldman became a volunteer supporting the San Francisco Ballet, organizations devoted to fighting the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and, naturally, craft and design artists and organizations. Generously sharing her time and knowledge with them was a good fit. “I was still going to craft shows,” she says.

Although she is being honored for her tremendous volunteer efforts, she’s also made smaller contributions to the craft field by purchasing the occasional handmade piece, usually jewelry. “I do it because I like a piece, or I want to support a new artist,” she says. “Every time I buy something, I feel like not only am I supporting the artist, I’m supporting the field.”

Fuller Craft Museum

Award of Distinction

Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton, Massachusetts, works to challenge common perceptions of craft, which it is doing, more and more, by presenting exhibitions with powerful social content.

↑ Fuller Craft Museum staff, including director Denise Lebica (front row, in blue) and chief curator of exhibitions and collections Beth McLaughlin (front row, in plaid).

Photo: Janet Bednarz

“I feel the days of beautiful things just kept at bay are waning,” says the museum’s director, Denise Lebica, who believes objects can be conduits for understanding and dialogue. “Museum audiences really want to see the power behind the object, and that power comes through exhibitions that are message driven and that have social impact.”

Take “Revolution in the Making: The Pussyhat Project,” which Fuller Craft’s chief curator Beth McLaughlin staged at the museum in 2018. The exhibition explored the pussyhat phenomenon that came in response to the 2016 election of Donald Trump. “I think it was an important project for the institution because it really demonstrated and underscored the responsibility, as a museum, to offer challenging content that reflects relevant social issues of our time and the power that we as cultural institutions have to effect social change and build community,” McLaughlin says.

Fuller Craft started as a community art museum with seed money from a local geologist named Myron Fuller. The doors opened in 1969 as the Brockton Art Center-Fuller Memorial. In 2004, the organization became Fuller Craft Museum and dedicated itself to the collection and exhibition of contemporary craft. Today, Fuller Craft’s mission is to make contemporary craft accessible to all, and it has made it a priority to focus on engaging the community, expanding its audience, advancing the field of craft, and sustaining its financial, human, and environmental resources.

“There is such a range of what people think of when they think of contemporary craft,” says McLaughlin. “For me, [the goal] is not necessarily to challenge the perceptions of craft, but to identify what people think it is and help them gain an understanding of the many facets it can have.”

She points to knitting pink hats for the Pussyhat Project as a good example. “It has really been viewed as something that everybody can participate in,” she says. “The hallowed definitions of ‘skill’ and ‘technique’ certainly are part of it, but I think there has been this opening of what people consider craft.”

ACC Awards programming is made possible through funding from the Windgate Foundation and the generosity of ACC supporters.

Help make American Craft Council programming possible

As a national nonprofit, we are documenting the evolution of the studio craft movement, honoring its visionaries, and providing craft resources for generations to come. We need your support to make it happen. Please consider donating or joining today to help make programs like the ACC Awards possible.