Pinnacle: 2018 American Craft Council Awards

Pinnacle: 2018 American Craft Council Awards

We live in a distracted age. at any moment, our attention can scatter in a thousand sparkly directions. Staying on task to achieve something meaningful requires dogged, committed action. Focus is difficult – and essential.

The 11 winners of the American Craft Council Awards profiled on the following pages are a testament to this kind of single-minded devotion. Nominated by other College of Fellows members, these artists – along with philanthropists and leaders – have dedicated themselves to craft for more than 25 years. They have reached a pinnacle few people attain because, whatever challenges and distractions they’ve encountered, they’ve kept going, one foot in front of the other.

Gold Medalist Jun Kaneko is a prime example. His manner is low-key, his drive fierce. At age 76, he lives to be in the studio every day, planning, making, pushing ahead. Jewelry maker Thomas Gentille chose his art form in large part because he knew there’d be no end to the challenges. “I decided this was for me because it was fighting me back,” he says. “There’s always another question about jewelry.”

To stay focused, fiber artist Consuelo Jimenez Underwood sets clear goals every 10 years. In 2019, she turns 70, and she’s not slowing down; “I want to weave as much as I can,” she says. Every day, Janet McCall, executive director of Contemporary Craft in Pittsburgh, asks herself, “What difference can Contemporary Craft make?” That simple question has driven groundbreaking exhibitions that have galvanized her community.

These achievers prove that, with patient persistence, the possibilities are infinite. We hope their words and work inspire you. For more inspiration, please join us at the Minneapolis Institute of Art on October 6 as we honor them. ~The Editors

Jun Kaneko: Gold Medalist

There is a sense of scale to everything Jun Kaneko does. At 76, the artist has nearly 250 solo shows on his résumé. His work appears in more than 70 museum collections. He’s been commissioned to make more than 60 sweeping public art projects, including last year’s 82-foot tower, Search, in his adopted hometown of Omaha, Nebraska. He’s known primarily as a ceramist, but he also paints and works in glass; he designed the sets and costumes for three major touring operas and co-founded two arts nonprofits. To tour any of his several cavernous studio spaces is to be dwarfed by 13-foot Dangos (“dumplings” in Japanese) and clay heads so large they take years to become leather-hard. No doubt, only a man with a plan – and serious ambition – could accomplish what he has.

When you dig deeper, though, you see the role of happenstance in his life. He was 17 when the most violent typhoon in Japanese history struck his native Nagoya at night. His family’s concrete house stood firm as the wooden structures around them collapsed. In pitch black, he and his father managed to pull in 36 people from the floodwaters through a second-floor window, saving their lives.

A mere four years later, fleeing an educational system he found stifling, he moved to California, even though he didn’t know anybody and didn’t speak English. The move didn’t seem daunting, he told the New York Times; he’d survived a typhoon. “After that, I wasn’t afraid of too much.”

Kaneko cites not ambition or planning but “pure accident” for the way much of the rest of his life has taken shape. Landing in Los Angeles in 1963, he ended up house-sitting for Fred and Mary Marer, serious collectors of contemporary American ceramics. He was amazed at their modest home, crowded with hundreds of objects. “It was completely jammed,” he recalls. “Ceramic plates and pieces are all over the floor.” The idea that they were worth collecting was equally amazing. Though handmade teapots and vases were common in Japanese homes, this body of work was different. It was an art form.

“It really did influence and shock me,” he says. “And I said to myself, ‘I should try this.’ ” Fred Marer introduced him to some of the prime movers of midcentury California ceramics – John Mason, Henry Takemoto, Ken Price, Billy Al Bengston, and Peter Voulkos; Voulkos, along with Paul Soldner, became his teacher. At the time, he didn’t know how remarkable these men were. And he didn’t see it coming, but ceramics became his passion.

Even meeting his devoted wife and partner, Ree, happened serendipitously. In 1982, he was driving with a friend to Canada. As they neared Pilchuck Glass School in Washington state, Kaneko suggested they stop and say hello to Dale Chihuly. At Pilchuck he met Ree Schonlau, who was taking classes there. She invited him to come to Omaha to join her workshop for artists who wanted to make work in an industrial setting. He’d been teaching at Cranbrook Academy of Art but had been thinking about moving and becoming a full-time artist. Omaha suited him; it was quiet, and there were old warehouses available at reasonable prices. He’s been there for 32 years.

So if Kaneko didn’t set out to take the world by storm with his thousands of exuberant sculptures – many of them massive and years in the making – how did it happen? The man himself provides few clues. While his work looms large, often in a vivid palette, he is small and soft-spoken. Though his impact has been huge – measured by the number of galleries, museums, collectors, and writers captivated by him – he can seem entirely self-contained. External recognition makes no sense to him – including the ACC’s highest honor, the Gold Medal. “I don’t feel like I deserve it,” he says. “I don’t know how to react to these things. I should be more excited about it, but I’m totally confused.”

Kaneko’s portfolio is not the result of striving and calculation, but rather the unfolding of a steady, irresistible impulse he trusts but can’t really explain. His ideas don’t strike like lightning; instead, every idea comes gradually into focus.

“I don’t try to force it,” he says. “Whatever my heart tells me, I will do it, if it’s a strong enough signal to make me do it.” He has one goal: “Doing my best.” And he’ll be the judge. “Sometimes I feel like I’m doing OK,” he says. “Sometimes I feel like I’m not doing that great, and I need to really develop more.”

Kaneko’s manner is gentle, but his drive is clearly relentless – and he counts on that. It’s his heartbeat, keeping him alive. “I’m following my intuition,” he says, “so my biggest worry is to run out of this desire of making pieces. If I lose that, that’s it.” He fears not a typhoon or a tornado but losing his life force. He may not understand the force or control it, but he treasures it: “Every day, you’re excited, and then you can’t wait to go to the studio. If you’ve got that basic thing resolved, then you’ve got it made.” So far, so good.

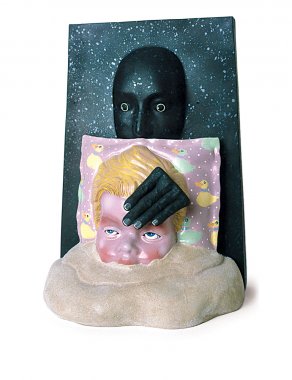

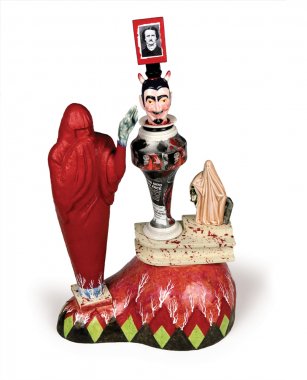

Mark Burns: Fellow

If you want to understand Mark Burns’ work, do not approach it with reverence. You’ll find it provocative, funny, and visionary, but he doesn’t want your awe; this is the man the Boston Globe recently dubbed the “John Waters of ceramics.”

Instead, consider how Burns was shaped by parents who scoured flea markets, restored antiques, and sold them out of the back of a truck. Imagine the family living in semi-rural Ohio, not far from the Ohio potteries, makers of piggy banks, collectible figurines, and floral-patterned dinnerware. “I saw that stuff every day,” Burns recalls, “and it ended up really affecting the clay work that I do.”

Consider that his father could be abusive, so young Burns and his sister steered clear. Burns spent hours in his bedroom drawing and making things. “In my real life, I couldn’t control what was going on, unless I went into a room and shut the door,” he recalls. It was the middle of the 20th century, Vampira was on TV pitching horror movies, and for 90 cents, you could pick up a kit to build your own plastic Dracula or Frankenstein. Burns became transfixed by monsters and along the way learned a lot about building figures on bases. “I’ve been making monster models for 47 years,” he points out.

If you want to appreciate Burns’ monsters, know that, when he landed at the University of Washington for grad school after earning his BFA at the School of the Dayton Art Institute in Ohio, his eyes opened wide. There he was – “just some guy from a cornfield” – working alongside Howard Kottler, Patti Warashina, and Robert Sperry. It was the funk period, unconventional work in clay was in vogue, and in that hotbed, Burns began to find his own, thoroughly quirky, voice.

Not that he dove right into making his own multilayered sculptural works. There were teaching jobs and, more important, the honing of his mad craft skills, which happened when Burns worked in the early 1980s for a Philadelphia art restorer, repairing broken braids on old Hummel figurines and the like. In that job, he had to work in an array of styles – the boss didn’t want his version of a Dresden milkmaid’s arm, he wanted a Dresden version – under strict deadlines. “I’d come in, there’d be maybe 50 objects on my tables, and each thing had a piece of tape on it with a number, and if it said ‘5,’ that’s how many minutes I got to rebuild what was missing.” Some days he did nothing but replace tiny fingers. The training was amazing; “I should’ve been paying them,” he quips.

Later on, keep in mind, Burns spent more than 20 years at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, teaching and running the art department, surrounded by all that Vegas kitsch in that most American of cities. He retired in 2012.

If you want to understand Burns, 67, forget about the deference of some artists toward their materials. He views clay “as an inert material that I didn’t feel any sort of spiritual or emotional connection to, no more than I did Play-Doh, or papier-mâché, or cardboard boxes glued together to make forts as a child.” And don’t check the work for the mark of the hand. Burns is partial to the anonymity of “the knickknack, the cheap souvenir – those things have an energy all their own,” he says.

Finally, after you’ve seen the work, even if you think it’s brilliant, don’t pay tribute in some grand way, because this new member of the ACC College of Fellows won’t necessarily buy it. “I’ve made some really good things,” Burns says, “and I’ve made some barkers. That’s just how it is.”

Beth Lipman: Fellow

When you look at one of Beth Lipman’s over-the-top still-life installations, you can almost feel the carnival spirit of a raucous banquet. You might faintly hear the noisy chatter, the clinking of glasses, the ritual laughter, the toasts and the asides. You can imagine the excesses of all the moments through the ages when prosperous people, throwing off all restraint, have come together to celebrate.

It’s a scene that’s been repeated in many cultural permutations since the beginning of time. And it’s that constant that drives Lipman. “I draw inspiration by looking at different points of time in history,” she says. In 2000, fascinated by the parallels between American capitalist society and the Dutch Golden Era of the 1600s, she began working in the still-life genre, which she loves for its capacity to capture an era through its everyday objects. “It’s a record-keeping of a moment,” she says. “That is something that I definitely identify with throughout my practice.”

Still lifes hold up a mirror to society, yes, but Lipman’s versions, though outrageously extravagant in form, are in a sense stripped down – in transparent glass, they’re devoid of color. She isn’t interested in the people who come to banquets; she’s the archaeologist who sweeps in after the party, spotting clues and recording notes about the society she’s discovered, “the human imprint.”

Her chosen medium records history in its own way. “The interesting thing about glass,” she says, is that “it is always capturing a moment in time. It retains every mark and every moment and movement.” The process is always revealed in the product.

Of course, history is imperfect and messy; it defies every ideal. Lipman is particularly grateful for recent projects that have allowed her to work with historical objects that aren’t as respectable as they might first appear. A few years ago, for example, the Chipstone Foundation in Lipman’s home state of Wisconsin gave her a piece from its permanent collection, an 18th-century Boston bombé secretary – parts of which were faked – as the basis for a commission. Lipman removed the counterfeit parts, burning some of them and incorporating the ash into hand-sculpted glass components. “I had the opportunity to create and redeem the object by creating a contemporary sculpture with this historical object,” she says. “That was really a powerful experience.”

As she’s logged years as an artist, Lipman, 47, has come to see that she’s also part of the span of history. Her earliest memories as a maker are of hours spent blending colors and sanding wood with her mother, who made Pennsylvania Dutch-inspired folk art. In fourth grade, she recorded her career goals; she wanted to be professional soccer player, a veterinarian, or an artist. Whatever she became, she recalls, “I knew that I would never stop making things.”

Today, she’s got her own children, who enjoy spending time in her studio and that of her husband, Ken Sager, who works with leather. “My daughters love to make things,” she notes. As it does, history could be repeating itself.

Mary Jackson: Fellow

When Mary Jackson looks back on her 73 years, she is amazed. She never expected to be a celebrated basketmaker with works in museum collections around the world. She never dreamed she’d count Prince Charles of England and Empress Michiko of Japan among her collectors. When she got the call in 2008 telling her she’d won a $500,000 MacArthur fellowship, she was so taken aback, she says, “I nearly fell down.” And when the Gibbes Museum of Art in her native Charleston, South Carolina, opened the Mary Jackson Gallery in 2016, she was floored. “That’s an honor that’s just hair-raising,” she says.

Now she’s been elected to the ACC’s College of Fellows. It’s all “more than I ever thought that would happen,” she says. “I never dreamt of any of this.”

Jackson learned to make baskets as a young child because, in her Low Country community, everyone did. For her aunts, her mother, her siblings and cousins, “this was our summer activity,” she says. There were no summer camps, movie theaters, telephones, or television. “When school was closed, this is what I did every day,” she says. By learning basketmaking, Jackson and her peers joined a tradition originating in West Africa some 300 years ago. Jackson’s ancestors were brought to the United States as enslaved people to cultivate rice, cotton, and indigo – essential crops in the plantation South. Generation after generation, “they kept this basketry tradition,” she says, as “evidence of where they came from and why” – and with the hope that “one part of our history would never be repeated.”

As a young woman, Jackson worked as a secretary. But when her baby boy (now 38) was diagnosed with chronic asthma, she quit work to be at home with him. She began making baskets again to bring in extra money and quickly made a name for herself by innovating on classic sweetgrass basket designs. Her unusual baskets were “a big success overnight. I had no idea,” she says. In 1984, she was invited to show her work at the Smithsonian Craft Show. Her reputation grew from there.

“I have enjoyed making these baskets,” she says, “although it’s very difficult.” Her description of the process bears that out. First, grasses must be harvested along the coast of South Carolina. If you’re gathering sweetgrass, you have to watch for snakes. If you need bulrush, which grows in the wettest areas, you have to beware of alligators. Plus, coiling grasses is hard on the skin, joints, and muscles. “My hands are very worn,” she points out, “and it causes poor circulation in your hand after a while.”

She’s also had to worry about the supply of materials. She spent about 10 years working with a Clemson University horticulturist, the Charleston mayor, nurseries, and landowners to propagate new sweetgrass plants because development was wiping out the habitat. As a result, sweetgrass is more plentiful today. But she wonders if children will want to devote themselves to basketmaking. “There are a lot more opportunities for them than there [were] for me,” she says.

None of this dampens her spirit. “The results of a basket are the thing that keeps you coming back again,” she says. “You’ve created something so beautiful, then the whole world loves what you’re doing … that’s the inspiration.”

Thomas Gentille: Fellow

A Thomas Gentille brooch is at once compressed and expansive, instantly recognizable and ultimately mysterious. Over a few square inches, one of Gentille’s pieces might present something like tilled pastureland, only in bright yellow and burnt red instead of green and brown, or a miniaturized high-rise tipped on its side, or Arctic water showing through cracked ice. They demand further study of the geometry of the lines, the interplay of the hues.

The 81-year-old Gentille, who lives in New York City, grew up in the suburbs of Cleveland, where his high school teacher Clay Walker introduced him to art, taking him on field trips to the Cleveland Museum of Art and teaching him painting, woodcut printing, and papier-mâché. Gentille adapted quickly to different materials – a flexibility that became a defining characteristic of his later work – and went on to study at the Cleveland Institute of Art under Joseph McCullough, who had studied with Bauhaus legend Josef Albers. McCullough passed along secrets about color that couldn’t be gleaned from instruction books or standard theory. “Mixing the color is one thing,” Gentille says, “but understanding the soul of color – that’s where Albers came in.”

Albersian juxtapositions have been at the heart of Gentille’s work throughout his more than five decades at the vanguard of jewelry. Employing his trademark unconventional materials – he opts for wood, pumice, paint, or bone far more often than gold or silver – he creates and manipulates tension. “I might lay one value against another if I’m trying to have something come forward and something recede,” the artist says. “I use [color] subconsciously all the time.”

Despite the expertise evident in his finished brooches – his preferred format – Gentille says making jewelry has never come easy. “I decided this was for me because it was fighting me back,” he says of his early years, “and painting and sculpture never fought me back.” He wears the scars of his work proudly, like badges of honor. “These fingers,” he says, holding up his hands, “this is all work-induced arthritis from holding, clamping down. When I clamp, my fingers are straight … so what looks like a deformity is actually a great tool.”

The emotional and physical effort that goes into a new brooch often pays off, but not always. “One hopes that one makes a good piece all the time; it doesn’t always happen,” Gentille says. “If it’s not good, it just doesn’t get seen. I have a box full of those.”

Challenge is an essential part of the jeweler’s work. “I stopped doing soldering a long time ago because soldering got so easy for me,” he says. Making a piece work on a technical level is only half the battle; the other part is aesthetic. “The question is: How do I make the connection of the different materials without making it look like a connection, without it being the most important thing?” Working in a range of materials, including his signature eggshell inlay, offers him a ready supply of problems to solve. “You learn that it’s never-ending,” the artist says. “It was one of the reasons why I started with it, because there’s always another question about jewelry.”

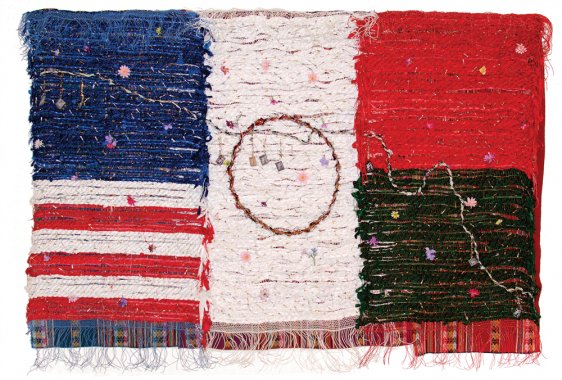

Consuelo Jimenez Underwood: Fellow

Since she was 9 years old, Consuelo Jimenez Underwood has had a plan. Just before she entered her second decade, she looked at the world around her and contemplated her options. Born in Sacramento, California, to a large family of migrant agricultural workers – she’s the second youngest of 12 – Underwood spent her youth picking fruit during the summer and into the school year. Her mother was a fourth-generation Mexican American, her Wixárika (Huichol Indian) father an undocumented laborer who arrived to the US knowing no English.

Even at an early age, Underwood realized that her family was at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. She understood that her classmates had more money and time – and therefore more opportunities – so she formed a “speed plan” to get ahead: “When you can walk, run. If you can run, fly – because you’ve got to catch up.” With in 10 years, she told herself, she would be the first in her family not only to attend high school, but also to earn her diploma and leave the migrant workforce.

That was the start of her setting 10-year goals. Every time the artist crosses into a new decade, she takes stock: In her 20s, she focused on raising a family of her own and supporting her husband, Marcos, while he got his degree. (“And meanwhile, I would just embroider everything that I had in the house.”) By 30, she had turned her attention back to herself and started college. By 40, she had earned three degrees: a BA and MA in art from San Diego State University and an MFA from San Jose State, where, by 50, she had become the art department’s head of fiber and textiles. Underwood also raised her profile in the art world – the Renwick and the Museum of Arts and Design, among others, acquired her work. By 60, she decided to leave teaching to focus on her own art – and to make up for lost time.

Her mixed-media weavings and installations look at the world through her tricultural perspective, aiming to deepen empathy. “I’d like my work to have a positive effect on a negative reality,” she says. Her work amplifies the voices of those who often aren’t heard, including undocumented families crossing the US-Mexico border in search of refuge and the countless nameless women behind centuries of textile craft. “I think that’s so cool that I have this opportunity to be a conduit for these voices,” she says.

Her Borderline series also gives voice to the Earth itself. “I remember crossing that border with my dad and my family, and I remember those fences,” she recalls. “I’d look at the plants and I’d think of the animals, and I’m going, ‘You know, this is so bad for the Earth.’ Who gives anybody the right to go somewhere and cut off the interplay between the sides?”

Underwood, who lives in California’s South Bay, now spends her days weaving with thread, wire, even safety pins, to tell stories about people, the environment, and the powers of the natural world. Still, she often worries that there’s not enough time. On the eve of a new decade (she turns 70 in April), her plan for the coming years is ambitious: “I want to weave as much as I can, the most beautiful things that I can ever think of for this world.”

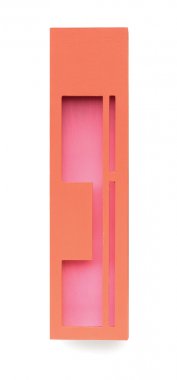

Thomas Hucker: Fellow

Thomas Hucker’s concert-pianist grandmother was an early example of the dedication a creative life requires, and of the rewards it offers. “It was the mastery of the instrument in order to produce the product,” says the 63-year-old furniture maker. “It was this kind of constant conversation – one, the love of the music, and then, along with that, was always the need to practice, the need to be skilled in order to participate in that world.”

Hucker painted throughout his childhood and, as a teenager, developed an affinity for furniture, with its recognizable combination of imagination and rigorous standards. “I like that feeling of creativity, but still, a certain kind of grounding that I felt with the crafts,” he says. Though Hucker loved the fluid, surrealism-tinged work of Wendell Castle, it was fifth-generation cabinetmaker Leonard Hilgner, his first furniture instructor, who schooled him in tradition and technique. “I’m incredibly grateful,” Hucker says, “because I think it’s critically important, as a young person, to get that stuff.”

Over more than four decades, Hucker’s work has displayed his classical training even as it honors his more experimental instincts. The surfaces of his chairs, tables, and sofas may swoop, swirl, or splinter, but they’re all underpinned by a precise, time-honored framework. He still favors music metaphors; he admires artists who make pieces he likens to the conceptual music of John Cage, but he considers himself more akin to a jazz musician, with a beat and a melody hidden within the improvisation. “You still may want to tap your foot or smile,” he says.

Hucker has lived in the New York City area for most of his professional life (he’s now in Hoboken, New Jersey), and as the region becomes less and less affordable, running a furniture studio presents a growing challenge. Hucker admits he sometimes envies his peers who opted for more rural locales. “I’ve felt like a freak here,” he says, “because being a woodworker in New York? It’s an oxymoron.” Still, the environment full of artists and thinkers has nourished him.

In his shop, Hucker gestures toward his in-progress pieces with visible delight. He praises the surprises that his collaborators, from bronzeworkers to locksmiths, present him with when they work on his pieces. Above all, he still relishes the feeling of pulling off an idea, a vision made manifest. “Do I walk in and confront this piece and feel a sense of joy in my immediate encounter with that object, or not?” he asks. “I think that’s important.”

Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada: Honorary Fellow

Sustainability drives Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada, but she views the concept broadly. “It’s not only sustainable in terms of ecology,” the Berkeley, California, artist says, “but it’s more like sustainability of values that we have lost.”

For one thing, the acclaimed shibori expert wants to revive an understanding of the importance of textiles to human existence from our earliest history. When you were born, she says, “you were wrapped in a cloth. And then, when you die, you will be in some kind of shroud.” Throughout life, she points out, we all wear clothes, various fabrics touching our bodies, part of the texture of the everyday. And that’s not to mention the centrality of cloth through the ages – to our homes, ethnic identities, and religious practices. “More so than ceramic or metal or wood,” she says, “cloth tends to be everywhere in one’s life.”

Wada came to her reverence for textiles as a child in Japan. “I was lucky to grow up still seeing the remnants of the old kimono practice,” she says, and the form remains vital to her own artwork. Her paternal grandmother, who arranged private art lessons for Wada when she was about 6, opened one of the first Western dressmaking schools in Tokyo. Her maternal grandmother was also attuned to fabrics, sewing, and mending – boro, as it’s called in Japan. Wada remembers rummaging through that grandmother’s box of silks and finding treasured clothes made even more beautiful by their “exquisitely patched” repair.

And she recalls visiting “fabulous fabric shops” in her hometown of Kobe with her mother and her sisters, choosing materials for outfits her mother would sew. Those trips nurtured their love for textiles, she says.

Now Wada, 74, worries that children and parents and grandparents don’t come together around textiles much anymore. Today, “mothers are too busy, and they don’t know, or they haven’t had a chance to learn it from their mothers.” That loss of generational learning has fueled her art practice, her teaching, the shows she’s curated, the four books she’s authored, the Natural Dye Workshop films she’s produced, and the textile-based organizations she’s founded.

Wada is keenly aware that the world of kimonos, handmade clothing, and careful mending is disappearing. But there are skills and traditions that must be preserved. Over the years, she has traveled the world to study traditional ikat, shibori, kasuri, and other forms of resist-dyeing, leading many tours to Japan, India, France, Italy, and China. And, since 1992, she has spearheaded the International Shibori Symposium, which has drawn textile enthusiasts from around the world to Mexico, Australia, and Chile, among other far-flung locales.

Besides her election to the ACC College of Fellows, Wada received the 2016 George Hewitt Myers Award from the George Washington University Museum and the Textile Museum, recognizing a lifetime of exceptional contributions to the field of textile arts.

“We’re losing connection with that past and the richness of textiles,” she says. Through her energies on many fronts, she’s helping to keep it alive and vibrant.

Susan Cummins: Honorary Fellow

Looking at Susan Cummins’ early life, you might not guess that she’d become one of the most respected art jewelry advocates working today.

She began as a student of fine art at Scripps College after a summer in Paris, London, and Florence. She’d seen world-famous paintings, sculptures, and architecture and wanted to learn more. She earned her art history degree in 1969 and about five years later opened a shop in northern California that sold pottery by her then-partner Beth Changstrom, as well as craft in other mediums. She didn’t start buying art jewelry until the mid-2000s, and rarely wears it even now. “It isn’t my style,” she says.

You could say Cummins, 71, came to focus on jewelry almost by process of elimination. In the early 1980s, she and Changstrom moved into a new gallery space in Mill Valley. They planned to exhibit several craft mediums, but there was too much local competition in ceramic, fiber, and glass. Almost nobody on the West Coast was offering jewelry, however, and the few East Coast jewelry galleries focused on European work. “So I decided, ‘All right, I’m a West Coast person. I’m just going to show American jewelry.’ ” That was the birth, in 1984, of the Susan Cummins Gallery.

The gallery became known for its innovative exhibitions and displays. The show “Jewelry as an Object of Installation” featured Bruce Metcalf, David and Roberta Williamson, and Kiff Slemmons, all of whom were making jewelry on a stand or as part of a vignette with other objects. Cummins especially loved displaying small paintings with like-minded jewelry pieces.

Ever since she chose jewelry (or it chose her), Cummins has been passionately devoted to its advancement as an art form, though her gallery closed in 2002. In 1997, she launched Art Jewelry Forum, which organizes gallery and studio visits for collectors in the US and Europe, funds critical writing, and offers awards for emerging and mid-career artists. AJF has published eight notable books on the medium, reflecting Cummins’ view that documentation is essential to confer legitimacy on any art form. “Unless you have the scholarship and the research,” she asks, “why should people take it seriously?”

Today, Cummins, now living in Tiburon, California, with partner Rose Roven, is working on a book about jewelry made in the tumultuous 1960s and ’70s.

What fascinates her about jewelry after all these years? First of all, because it’s relatively small and worn on the body, it’s artistically challenging to make. “I like the limits jewelry imposes on the object,” she says, “and I love to see what an artist can do within those limits.” Second, in her favorite kind of work – what she calls “power jewelry” – she sees the weight of history. “It often has an overlay of a symbolism, a mystical or magical or spiritual quality, which I think the first jewelry had,” she says. “It has a conviction about it.” With her decades of devotion to small, beautiful, meaningful objects, this Honorary Fellow also radiates conviction.

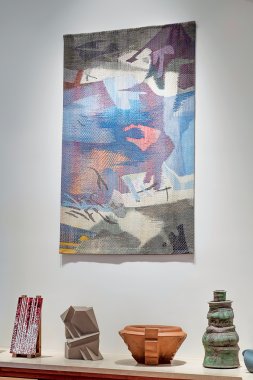

Contemporary Craft: Award of Distinction

Tacked on a board in Janet McCall’s office is a well-worn sheet posing two vital questions: “What change can we make in the world?” and “What difference can Contemporary Craft make?” Those two queries drive the Pittsburgh art organization, where McCall is executive director. Its artist- and community-focused initiatives include award and exhibition opportunities for makers, a shop selling their work, cutting-edge shows examining pressing social issues, artist residencies at local middle schools, on-site studio classes, maker programs serving homeless youth and nursing home residents, and an apprenticeship for emerging black arts administrators aimed at diversifying the leadership of art organizations. By showing work that reflects a variety of perspectives in its brick-and-mortar space, located in the city’s Strip District, as well as at their satellite gallery in a busy downtown light rail station, the organization also aims to help people of all walks of life – whether or not they have a background in art – relate across difference.

Engagement is a big part of their mission. “We’re not here to hold forth as art experts,” McCall explains. “We’re really here to provide an opportunity for conversations and discovery and making, together.” One way is through their biennial social justice initiatives, traveling exhibitions examining sensitive issues. Since 2013, the organization has mounted three shows on difficult topics – violence, mental health, and homelessness – working with experts in each field. Accompanying materials – free, hands-on, artist-designed projects, curriculum guides, and lists of outside resources for further learning – help audience members leave the show feeling empowered. “Our hope is that every person coming in to see one of these social justice shows will go out the door thinking, ‘There’s something I can do,’ ” McCall says.

Contemporary Craft was founded as a nonprofit in 1979 by philanthropist and art advocate Elizabeth “Betty” Rockwell Raphael, although its roots extend to 1971, when it opened as a pop-up craft shop just outside the city. The organization has changed over the years, but, McCall says, it has stayed true “to Betty’s very strong commitment to the community and making sure that art was accessible to everyone.”

For more than 20 years, McCall and director of exhibitions Kate Lydon have been at the helm of the organization, developing craft as a tool for social change, empathy, and understanding. After all, creative expression is a vital part of the human experience, McCall says, and something to be shared. “My job is to make art available to everyone and to help them understand that it’s a tool; it’s a resource that can lead to a better life and better understanding of themselves.”

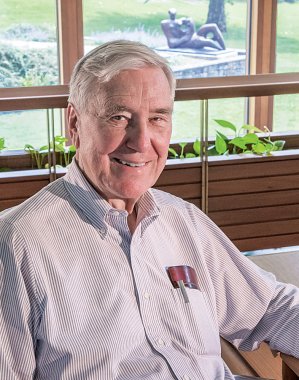

Marlin Miller Jr.: Aileen Osborn Webb Award for Philanthropy

Though Marlin Miller Jr. has made a name for himself in the business world – he founded medical device company Arrow International, leading it for 28 years, and is president of Norwich Ventures, an entrepreneurial med-tech company – it’s his friendships with artists and makers over the years that he particularly treasures. “I think back with great fondness on the fact that my first roommate in college was an art student and that I had the good fortune to marry two artists,” says Miller, 86. “If those had been different situations, my life would have been entirely different, I’m sure.”

In South Bend, Indiana, Miller’s childhood revolved around sports. He went to museums on occasion, he says, but meeting artists, especially during his college years at New York’s Alfred University, represented “a great change for me.” Craft became a focal point. Miller’s first wife, Marcianne Mapel Miller, was a potter, and during his military service in Europe after graduate school, the couple visited ceramic artists whenever they had the chance, collecting what they could afford.

After Miller’s service ended, he and Marcianne moved to Reading, Pennsylvania. As business prospered, they began filling their home with works by some of their favorite makers – Wayne Higby, Peter Voulkos, and Cynthia Schira, among others. Collecting was satisfying personally, of course, because it allowed Miller to live with objects he loved, but he notes it also serves a larger purpose: “Every time you buy a piece of art from an artist,” he says, “you’re really helping the whole movement, because it’s letting that artist do the next piece or the piece after that.”

After Marcianne’s death, Miller married fiber and watercolor artist Regina “Ginger” Gouger in 1991, and the two built a new house in Reading, with plenty of room to display their collection. The dining room table is by George Nakashima, and a sculpture by Henry Moore – long a dream acquisition of Miller’s – sits in their backyard.

Miller’s contributions extend well beyond collecting. In 1972, he joined the board of trustees at Alfred, home of the renowned New York State College of Ceramics, where Marcianne earned her BFA, and he later established a memorial fund in her name. For almost a decade, Miller also sat on the American Craft Council board, and in 2005, he co-founded GoggleWorks Center for the Arts in Reading. GoggleWorks hosts a full roster of exhibitions; its classes serve more than a quarter-million people each year.

For all that Miller has given the world of craft, he is adamant he has received even more. Besides his collecting and philanthropy, he has become a practitioner; he maintains a ceramic studio at his home, a welcome retreat. “A good day,” he says, “is when you start to make some things, and maybe some new shapes that you haven’t made at all before, and you can actually take them off the wheel as a finished piece. That’s a good day.”