Medium Man

Medium Man

It’s March 17, 2006, and the applause in Omaha’s Orpheum Theater is deafening. The stage lights have just darkened, ending the world premiere of a new production of Madama Butterfly.

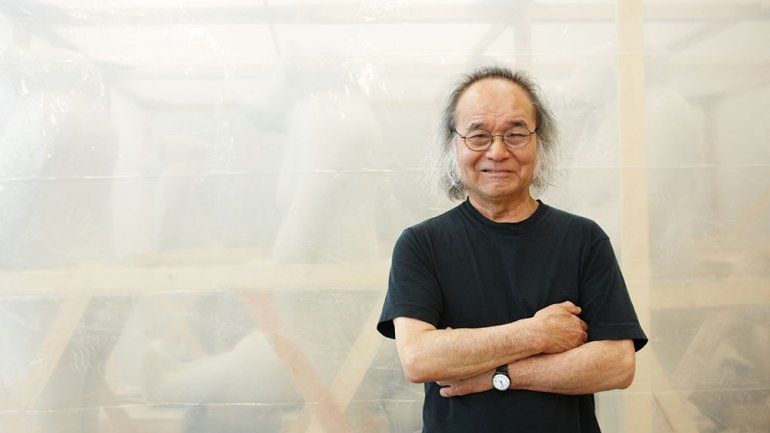

The performers and conductors take their bows. Then, slowly, from the side of the stage, comes the man responsible for making the night – Jun Kaneko. The artist is dressed in black, a stark contrast to his costume and set designs, which are dominated by in-your-face reds, blues, greens, and yellows. He smiles, shyly brushing tousled gray hair from his face; while he’s no stranger to success, a standing ovation is a new experience. Best known for his large, whimsical ceramic sculptures, Kaneko has work in more than 70 museum collections; he has executed more than 50 public art commissions. But this is his first foray onto the stage.

Fast-forward seven years, and designing opera sets is no longer an experiment. It is just one of many mediums, including clay, glass, and painting, for which the Omaha-based artist is known. And it is one of several mediums in which Kaneko, 70, continues to experiment as his multifaceted career approaches 50 years.

“There aren’t very many artists who are acclaimed and accomplished in painting, glass, sculpture, and opera sets,” says Robert Duncan, a longtime friend and collector, who last year joined the American Craft Council’s board. “He does it for the challenge – the knowledge that he can expand his capabilities into another medium.”

The breadth of Kaneko’s work is truly unusual. But if you talk to him, flowing from one medium to another is incidental. He believes every new project requires the same things: imagination and a deep understanding of materials. And every project, whether a set design or a bronze sculpture, begins the same way – with a “creative spark.”

“When you think about how creativity starts, it doesn’t matter what you’re working with,” he says. “You always start at the same place.”

Kaneko was born in Nagoya, Japan, in 1942. When he was a teenager, his mother, an amateur painter, discovered piles of drawings in his room and arranged for him to study with the painter Satoshi Ogawa. At 21, Kaneko moved to Los Angeles to study painting at the Chouinard Art Institute.

Shortly after arriving, the young artist was introduced to Fred Marer, a math professor at Los Angeles City College with an extraordinary ceramics collection. “When I saw his collection, I just wanted to try,” Kaneko recalls. He immersed himself in the collection that summer while house-sitting for Marer and his wife. He was hooked. The Marers introduced him to several ceramists in the area, including Jerry Rothman, who evidently saw such promise in Kaneko that he gave him a huge supply of clay and offered to fire anything he made. His first piece? A flat slab. “I was a painter, so that made sense,” Kaneko says.

From 1966 to 1970, he studied ceramics at several schools, including the University of California, Berkeley, and California’s Claremont Graduate School, where he eventually earned an MFA. He went on to teach at the University of New Hampshire, Scripps College, and Rhode Island School of Design, before landing at Cranbrook Academy of Art.

It was in 1981, while he was teaching at Cranbrook, that Kaneko was invited by Ree Schonlau – now his wife – to create an experimental work at a brick factory in Omaha. (The city’s Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, which she cofounded, was born of that workshop.)

Something clicked. “I’d been in big cities, but I don’t like how it takes so much extra energy to live in big cities,” he says. “In Omaha, space is easy to find, people are nice, and it’s easy to get around.” He returned the following year, and in 1986 permanently relocated.

It was during those early years in wide-open Omaha that he created his first Dangos, geometric works whose title is taken from the Japanese phrase for “rounded form.” Today, some of his sculptures weigh more than three tons and stand more than 13 feet tall. His studio – a 238,000-square-foot complex of seven warehouses renovated over the years – easily accommodates such boundless exploration.

For Kaneko, the spark that launches a new work can be anything – an opera, a book, an object. The hard – and sometimes scary – part is turning that initial spark into something concrete. To even begin, you have to choose “one line, one color, one space,” he says. “And when you decide on one option, you’re excluding all the others.” There are no rules as you continue. “The making process is a fluid thing. You have to just grab it and keep going.”

In 2005, the artist and his wife launched a nonprofit called KANEKO, dedicated to exploring how people in fields from art to science to philosophy find and nurture those sparks. This “open space for your mind” hosts lectures on the creative process by nationally known figures, from filmmakers to artists to scientists to business leaders; art exhibitions, including a collection of Kaneko’s own work; and experimental performances and events that embody this spirit, such as the Omaha Symphony’s New Music Symposium and the Great Plains Theatre Conference. The organization, like creativity itself, “is a living thing,” Kaneko says, “so it keeps growing and changing.”

As does Kaneko’s career. A walk through his studio reveals just how busy he is. Brightly colored costume and set drawings from a recent production of The Magic Flute by the San Francisco Opera are taped to the walls and scattered on tables. Steps away are a half-dozen abstract paintings. Two stories below stand 6-foot-high handbuilt ceramic Tanuki sculptures, forms inspired by Japanese raccoon dogs; 36 of them are headed for Chicago’s Millennium Park for a temporary installation in 2013. In another room are drawings – prep work for large handblown laminated glass panels that will form a 56-foot illuminated tower in downtown Lincoln, Nebraska, next autumn, part of an urban plaza public art commission.

Despite the wide range of mediums, one thing nearly all the works do share is an identifiable aesthetic: the juxtaposition of black and white, and blues, reds, and yellows, in Kaneko’s signature drip-line-dot approach. It adds a playful quality, which, often coupled with uncommon shapes and experimental textures, is friendly but unexpected, and tends to draw people into conversation.

“His works can be very ‘chatty,’ ” says Jorge Daniel Veneciano, director of the Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln, which hosted an exhibition of Kaneko’s work in 2009. “Their colorful vibrancy creates an ethos you wouldn’t expect from the man you meet, who’s more reserved in speech.”

Indeed, a few minutes with Kaneko reveal a quiet, almost mysterious personality. He is more than willing to answer questions about his work, but discussing his success isn’t what interests him; he knows there are more projects to tackle, more problems to solve. And until he has exhausted every last creative spark that comes his way – which won’t be anytime soon – he will continue to explore.

Ashley Wegner is a freelance writer and editor in Omaha, Nebraska.