India: Weaving it Together

India: Weaving it Together

Nestled along the banks of the Sabarmati River, the city of Ahmedabad in India’s western state of Gujarat boasts a rich textile history. Industrialization in the 19th century made the city a textile capital, but its heritage dates back centuries and continues to fascinate and inspire designers today.

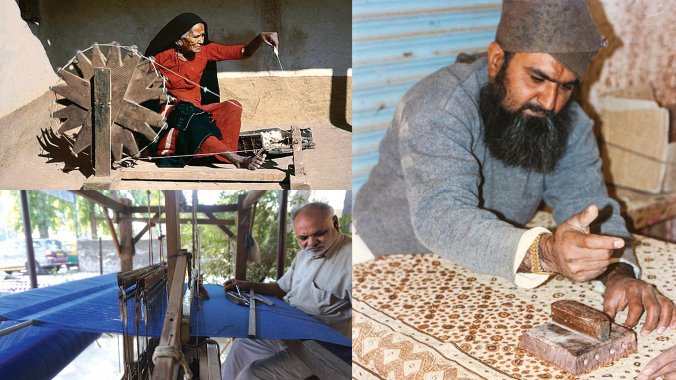

When fabric artist and designer Archana Shah was in school at Ahmedabad’s National Institute of Design, she traveled to remote corners of India to learn from artisans working in traditional weaving, dyeing, printing, embroidery, and ornamentation. After graduating in 1980, she was eager to collaborate with these artisans, combining her design skills with their artistry to create new pieces; she started her fashion company Bandhej in 1985. The name refers to a style of tie-dyeing, in which the fabric is bound many times to create intricate patterns of small dots.

Also known as bandhani, the technique dates back more than 1,000 years. “I must have done 80 collections with bandhani,” Shah says. “The essence of the technique should remain. But basically you rearrange the patterns, or you use different colors or different positions of the same dots.” She uses the bandhani textiles she designs to create traditional clothing – saris, dresses, and kurtas (a tunic-like top) – as well as more modern cuts of kurtas, blouses, and skirts.

What began as a fascination with an ancient craft has grown into a deep commitment to the values embodied in the handmade; Bandhej promotes environmental, economic, and cultural sustainability. Shah notes the smaller environmental footprint of handcrafted textile production compared with that of huge mills and factories. And as part of her commitment to employing artisans, some of whom she’s been working with for more than 35 years, she challenges herself to find different designs using the same techniques each season. Seeing artisans plying their trade also encourages the next generation to learn the craft, she says.

She even uses khadi, a handspun cloth that Gandhi championed during India’s Freedom Movement in the early 20th century. Reviving khadi, Gandhi argued, promoted self-sufficiency and helped to restore a part of India’s cultural history he feared was being lost to colonization. Shah’s use of the fabric reflects her belief that the movement’s aims endure. “I think the future really is in the handspun, handwoven fabric,” she says.

Shah’s creations can take nine months to move from idea to product. She designs her collections from her Ahmedabad studio, thinking through every detail of surface design and cut. She consults with the artisans and samples color palettes, and when she is satisfied, the artisans begin their work, from weaving the cloth to embroidering and embellishing it, before the collection appears in Shah’s seven stores across India. Whether she’s drawing on bandhani, khadi, or another of India’s traditions, Shah has found that the well never runs dry. “Even today I keep finding new ways and new interpretations,” she says.

Shah also continues to explore India’s vast textile traditions. In 2012, she published Shifting Sands: Kutch, which examines the region’s textile heritage, including how it connects to the landscape and culture. She’s researching another book, this time surveying sustainable textile practices and how they might endure. “I think that’s what I leave behind,” she says, “so hopefully these crafts can continue.”

Shah compares the “slow fashion” trend to the “slow food” movement, whose popularity has grown steadily over the past quarter-century. Her hope is that handmade clothing will follow a similar evolution, as more and more people embrace the beauty, sustainability, and worth of artisanal textiles.