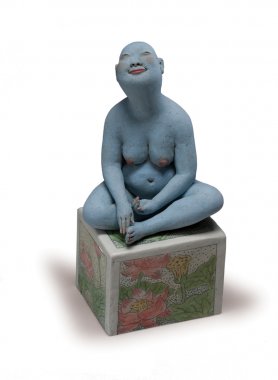

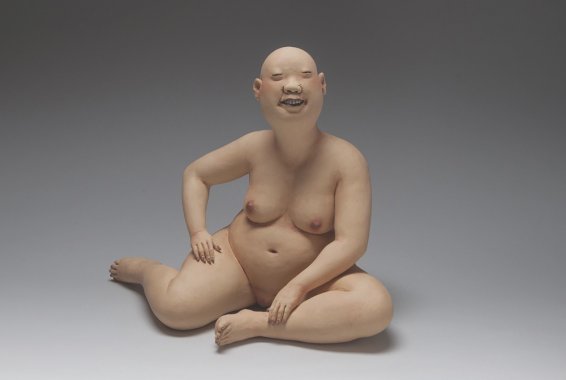

Joie de Vivre

Joie de Vivre

Esther Shimazu was 5 years old when she committed her life to clay. She was in kindergarten and fell in love while making her first pot. Yet from the beginning, she felt what she calls the “push-pull” – wanting to create figurative work instead of functional ware. It wasn’t until she was a student at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, studying advanced ceramics far from her home in Hawaii, that she got up the guts to sculpt a nude.

“I asked if I could, and the professor patted me on the back and said, ‘Go ahead,’ ” she recalls. “I made my first nudes in Massachusetts because nobody knew who the heck I was,” Shimazu says. “I really wanted to do them; they always seemed to be my goal, but on the other hand, it was deadly embarrassing.”

Ever since that day some 40 years ago, she’s been sculpting nudes. Getting past her own taboos about the body was one barrier. She also felt vulnerable as one of the only students of color in her UMass classes; plus, she was making work unlike others’.

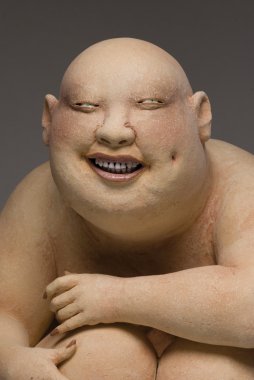

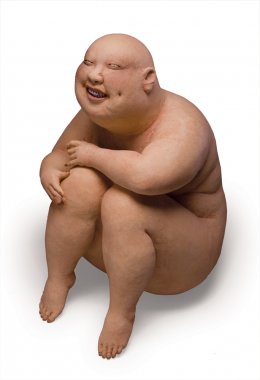

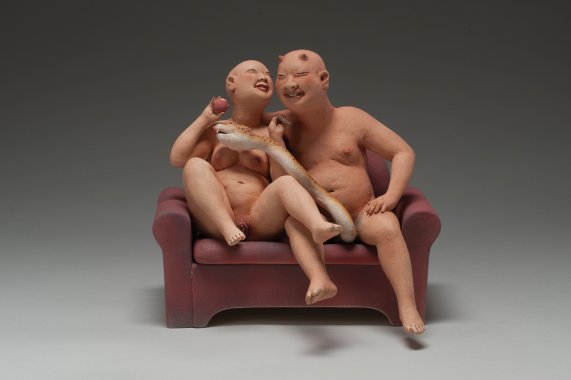

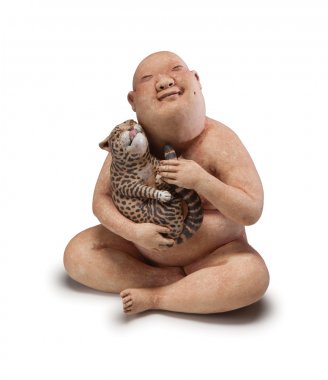

Today, her sculpture is so unmistakable that even casual ceramics fans are likely to know it: fleshy, naked, hairless, gender-blurry Asian people. They are usually smiling, and they always have incredibly detailed toes. Why does she put so much time into those digits? “Somebody has to,” Shimazu deadpans. “Feet are great.”

“Esther has her own unique voice, and she is speaking to us through her art, through her very precise details, down to the toes,” says California gallerist John Natsoulas, who has been representing Shimazu since 1992. She also occasionally sculpts animals – mostly grinning dogs, and those canines have carefully carved, er, canines.

When he first met her, he says, she was shy and not necessarily confident in the wider appeal of her work. It took some persuading before she believed that the ceramics she intended to represent herself, and Hawaiian culture, would resonate with collectors from elsewhere. But, as Natsoulas points out, Shimazu’s collectors aren’t limited to the islands. They tend to be “women with a sense of humor,” he says.

For her part, she says, “if it weren’t for John, I wouldn’t have a career.”

Shimazu’s grandparents emigrated to Hawaii from Japan in the 1920s, and her parents grew up on a huge Maui sugar plantation. Her father joined ROTC in college and was a student on Oahu when Japanese planes flew over en route to Pearl Harbor. He and other Japanese Americans were soon kicked out of ROTC, but he was later allowed to enlist in the Army’s 442nd Infantry Regiment, one of the most decorated units in US military history. The regiment, almost all Asian American, suffered heavy losses in France and Belgium before helping to liberate the Dachau concentration camp in 1945.

“My father told my mother that after surviving that war, anything else was just a bonus,” Shimazu says.

Her parents met after Shimazu’s father finished engineering degrees at top Midwestern schools through the GI Bill and returned to Hawaii. Shimazu’s maternal grandparents were not sent to an internment camp, but they had to hand over all Japanese literature, photos of the emperor, and even cooking knives. Local authorities also outlawed fishing and imposed strict curfews. Perhaps because both parents had survived such hardships, they encouraged all six of their children to at least dabble in music and the visual arts.

“Everybody was fairly artsy-fartsy, but clay was my thing,” says Shimazu, who works on a back-porch studio within sight of the Pacific Ocean. Her modest ranch house is in Kailua, on the northeast shore of Oahu, across a misty, tree-covered mountain range from the touristy beaches and bustle of Honolulu. She shares the home with one of her three sisters, who works as a jeweler and industrial designer, and a cat named Midge.

Housing is crazy-expensive in Hawaii, and Shimazu knows she’s lucky to be making a living as an artist in her home state. Her career has been possible, she says, only because Natsoulas promotes her ceramics around the world and because of her initial career opportunities with the US Army.

Shimazu worked “a whole bunch of wacky jobs” before landing full-time work in 1985 supervising amateur artists at a military craft studio. For seven years, she built pinch-pots and taught jewelry to kids, spouses, and civilian staff, and in the evenings and on weekends she made her figures. Fort Shafter closed the studio in 1992 – “It was too good to be true,” she says – and Shimazu was reassigned to a primitive Macintosh to create computer graphics. Around that time, she met Natsoulas, who came to her studio while visiting Oahu to install work by another artist.

“He liked my work, and he wanted me to get the hell out of [my day job],” Shimazu says, who has a fondness for salty language. “I wanted to get out of there too, but, you know, job security.”

It took three years, but he finally persuaded her to become a full-time artist. After several trips to bring her and her work to the mainland, including the SOFA Expo in Chicago, he asked Shimazu point-blank how much money she needed to maintain her home on Oahu. “He said, ‘Fine, we can do that,’ ” Shimazu says, “and he did.”

“Esther is one of Hawaii’s most successful artists,” says Aisha Buntin, a co-owner of Robyn Buntin gallery in Honolulu, where Shimazu’s works are prominently featured among traditional Asian art and antiques. A swanky hotel gallery on Maui also carries her work, as do Studio 7 gallery on the Big Island and the shop at the Hawai’i State Art Museum in Honolulu. Hawaiian collectors appreciate her work, and she’ll occasionally donate a piece to help a local charity.

“I think this year they are getting a dog or maybe a pig,” she says.

Now 62, Shimazu has evolved from an artist so steeped in a conservative culture that she could sculpt nudes only halfway around the world to a woman revered as an artistic ambassador for her state.

Shimazu shrugs off the accolades. “The island is like a small town,” she says. “It’s my home.”