Keep Your Damn Flowers

Keep Your Damn Flowers

Randi Solin didn't come naturally to glass. But her unique, robust pieces stand on their own.

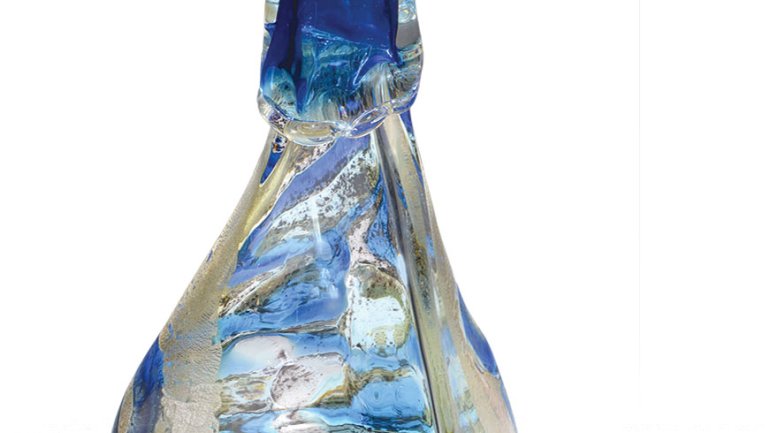

Randi Solin doesn't want you to put flowers in her glasswork. Instead, she's adamant that you see her pieces for what they are: abstract expressionist art closer to paintings than fragile bud vases. Solin deals in substance; her works average 12 to 15 pounds of glass, with a thick, transparent exterior layer acting as a window on a colorful, lucent interior image. And while her vessels have openings, that doesn't mean they're waiting to be filled. "They have a hole in them because they're made with a glass blower; that's it," she says.

Solin never expected to be an artist. Growing up outside Washington, D.C., in the 1970s, she became interested in politics at a young age. When she was 12, her family moved to Manchester, Vermont, and she re-established her high school's student council, dormant for decades, and organized one of the first pro-choice rallies in the state. "I wanted to be a senator. I wanted to affect people's lives," she says. When she toured Alfred University, her father's alma mater, she planned to pursue political science. But a trip to the art department changed all that.Walking on a dark catwalk, she looked down and saw what appeared to be liquid light; it was an artist blowing glass. "I thought, whatever he's doing, I'm going to do," she says.

Solin had never taken an art class, but she was accepted to the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred, one of the best art schools in the country, on the basis of her academic and extracurricular record. Her portfolio consisted of seventh-grade industrial art projects and photographs developed in the darkroom she built in her house. "Nobody with my background had ever applied to the school," she remembers.

Her background wasn't such an asset, though, as she began to grapple with the nitty-gritty demands of art school. "My peers were the very best artists from their schools, and I didn't even know the basic terminology," she recalls. She remembers panicking at an assignment to draw "negative space" between two pieces of paper; she had to ask other students what the term meant. Stress almost derailed her freshman year. Her weight dropped to 87 pounds, and she developed a bleeding ulcer and severe jaw tension. As one way to cope with the pressure, she followed the Grateful Dead, as she had in high school, enlisting other Alfred students to accompany her on long road trips. "Dancing is my drug of choice," says Solin, who found the concerts cathartic. She carted along her projects, once constructing a 12-piece plaster sculpture in the parking lot of a Dead show in Richmond, Virginia, fetching water in a bucket to keep the plaster pliable.

She was coping, but not thriving. A warning from the university snapped Solin out of her doldrums. She began working nonstop on her art, staying in the studio until it closed at 2 a.m. Ultimately, she graduated and won a scholarship to Pilchuck Glass School, to study with William Morris and other noted glassblowers. At first, she had that familiar out-of-her-element feeling; an instructor chastised her when she didn't know how to set up her bench in the traditional Italian style. Midway through the course, though, Morris called everyone over to watch her work. "He said, ‘Look at this chick! She's really doing something interesting,'" Solin remembers.

After Pilchuck, Solin moved to San Francisco and taught school for 10 years, while blowing glass in the evenings and on weekends, continuing to experiment. "I would do whatever it took to keep moving it forward, and keep my hands on the material," she says. She bought a rundown house in Mount Shasta, California, and built a studio where she began to create her first real body of work. Eventually, she came home to Vermont and settled into her current Brattleboro studio in 1999.

Solin incorporates techniques from both American and classic Venetian styles. Out of those traditions, she's developed a unique, experimental approach, which involves amassing thicker glass than most glassblowers use and layering color on color like a painter. Her methods flout Italian glassblowing standards, which prize glass blown as thin as possible. But for her there are no right or wrong approaches. "I'll cut it, I'll slap it on. I don't care about anything but the idea coming across," she says.

Many of her ideas come from National Geographic, through which Solin does her vicarious traveling. One series, Kauri, mimics the form of a tree sacred to New Zealand's Maori people. A story on melting polar ice caps motivated her Greenland piece, in blue, black, white, and fine silver foil. Malibar takes its name from a spice-trading city in India, its shape mimicking a sari. Uruqin, named after dunes that form a path where the Bedouin walk their camels, evokes a monochromatic landscape.

Making her hefty pieces is physically taxing; she says she often emerges "beaten down and sweaty." But she's not complaining; the exertion gives her a "sense of feeling alive," she says. Even at Alfred, where she had decided to become an auto mechanic if an art career didn't pan out, she had what she terms a more masculine approach to work. Engaging viewers fully, luring them to "take a break from what's happening in their heads" is Solin's intention. "People say, ‘I could lose myself in this' " as they gaze at her work, she says. Buyers of her larger pieces are often moved at a deep level. People show her their goose bumps; sometimes tears well up. "They act like ‘I don't want to live without this thing,'" she says.

Which brings Solin full circle to her original goal: touching people's lives. Her art brings harmony into homes and inspires ease in the midst of harried lives.

Solin insists that nothing in her work should be interpreted literally, though people often point to images of everything from nymphs to fish in her designs. And she continues to be baffled by the impulse to stick flowers in glass. Vessels in her Kauri series have tiny openings; still, she recalls a potential buyer speculating that there was enough space for a pussy willow.

"Sure," was her response, she says, laughing. Then she adds more seriously: "I have a ‘no carnation' policy." If you put a carnation in one of her pieces, she says, "I'll come to your house and take it back."

Katherine Jamieson is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Ms., and Washingtonian. Two of her essays were recently included in The Best Travel Writing 2011.