Mobile and Movable

Mobile and Movable

Like many women, Helen Drutt tends to recall occasions by what she wore. In her case, the memories are of extraordinary pieces of jewelry by some of the world’s best and most innovative makers.

“I remember wrapping a Stanley Lechtzin work in a handkerchief and taking it to Ireland for the World Crafts Council meeting in 1970. I proudly wore this huge mica-and-pearl electroformed brooch ‘blazing’ on my breast,” says Drutt, a pioneering dealer, scholar, and advocate for studio craft. For the opening of the big Salvador Dalí show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2005, she donned something appropriately surrealistic – a nose covering, cast in gold from her own nose, by metalsmith Gerd Rothmann. (The crowd was so blasé, or maybe nonplussed, that no one said a word about her accessory.)

“I am passionate about jewelry,” Drutt says. “There is no doubt that that is true. I wear jewelry every single day, even at home. I like to wear jewelry just as I enjoy using beautiful dishes for dining. It is great to have works of art that you can take with you wherever you go, and important to surround your life with works by artists whom you know, and believe in their art.” In 2002 she gave more than 800 pieces of studio jewelry from her personal collection to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

She spoke with us recently from her home in Philadelphia about why jewelry is, for her, as much an educational tool as an element of style.

What sparked your interest in jewelry?

I had been instrumental in the formation of the Philadelphia Council of Professional Craftsmen with Richard N. Jones, a Baptist minister. We made a decision to form a professional group of craftsmen, through which we could educate the community about the craft resurgence, and by doing so encourage museums and institutions to develop exhibitions. Hopefully, the crafts would eventually be regarded with stature equal to that of painting, sculpture, architecture, and photography. Remember, this was the late 1960s, and the crafts were struggling for recognition.

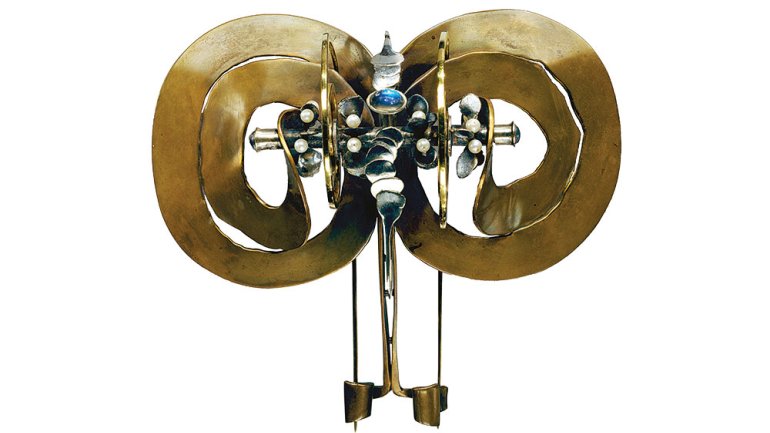

One of our initial meetings took place at the home of Stanley Lechtzin. I remember that he appeared with an electroformed silver, tourmaline, and pearl brooch in his hand. I had never seen anything like it. I think I screamed, because it was extraordinary. I realized then and there: Something was happening in the field of jewelry that was totally innovative and new – that ornament was ready to take gigantic leaps into the world of art.

How do people respond to the jewelry you wear?

My position in the field of modern and contemporary crafts is not just about jewelry. Jewelry was a vehicle to assist me in educating an audience. I’ve said this a hundred times: You could not walk into a meeting holding a chair, or a pot. But if you wore jewelry, people would notice: “Well, what is that? Tell me about it.” Then you could discuss what was happening in the craft field.

Jewelry was a catalyst for questions and inquiries. It was mobile and movable. I remember being delayed in a railroad station and missing my train because the janitor began to ask me questions about my Albert Paley brooch. Before I knew it, the train left and I was still talking, trying to explain to her the concept of the fibula [which is Latin for “brooch”]. I was at a dinner party last night at the home of Vienna Secessionist collectors. I wore a brooch by Helfried Kodré, a contemporary Viennese artist. It served as a catalyst ... we discussed a range of aesthetic concerns within the Austrian world, and resurrected the importance of Inge Asenbaum, who collected Wiener Werkstätte and supported contemporary European jewelry with exhibitions in her Galerie am Graben. I also love the fact that sometimes a cab driver will say, ‘Lady, you look really great,’ or a train conductor will sit beside me to discuss the jewelry.

What do you have on right now?

Two rings, one by Max Fröhlich, the other by Miye Matsukata. My wedding band and two silver bangles by Breon O’Casey. I just removed my Eleanor Moty brooch. My earrings were made by Georg Dobler.

Your thoughts on current directions in jewelry?

The concept of a broader use of a range of materials is exciting. I love the exploration. Some artists are working with wood in a very innovative way – not just carving, but creating necklaces using slats of wood, burning wood, and also using natural twigs and embedding pearls or stones within them. There are artists using found objects in the most innovative ways that I’ve ever seen, setting them as if they were diamonds or sapphires or rubies. We also observe a return to a dedicated commitment to traditional and nontraditional aesthetics, which include metals – i.e., gold and silver – intensive beadwork, chains, film, paper, photography. There is a great diversity in which one can explore the concept of ornamentation in modern and contemporary jewelry. There are no longer any barriers.

Further reading: Jewelry of Our Time: Art, Ornament and Obsession by Helen Drutt English and Peter Dormer; Ornament as Art: Avant-Garde Jewelry from the Helen Williams Drutt Collection, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, by Cindi Strauss. Joyce Lovelace is American Craft’s contributing editor.