The Open Door

The Open Door

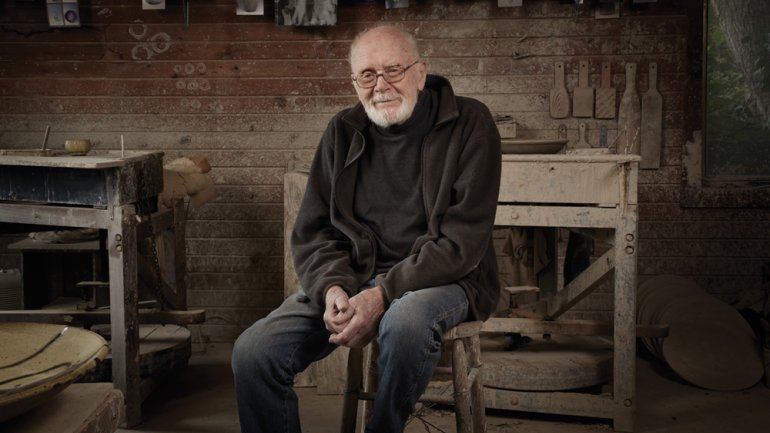

Warren MacKenzie is giving directions to his home. It isn’t, he explains, the easiest place to find. But his guidance is practiced – perfected, even. Over the six decades he has lived and worked in this modest house, on a wooded lot at the edge of Stillwater, Minnesota, the potter has invited hundreds, if not thousands, of guests.

Inviting people in – to his home, his studio, his life – is as much MacKenzie’s signature as the mark he presses on his pots. And over his career, including 37 years at the University of Minnesota, this openhearted generosity has helped launch generations of ceramists.

“Ask anybody who’s making studio pots in the Upper Midwest,” says Sarah Millfelt, director of the Northern Clay Center, a Minneapolis gallery and nonprofit devoted to ceramic arts. “I’m sure through the seven degrees of Kevin Bacon, they could connect themselves to Warren in some way.” Millfelt, in fact, studied at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls with Randy Johnston, a former student of MacKenzie; she patterned her relationship with Johnston after his with his teacher.

That’s no coincidence. “I’m proudly part of Warren’s legacy as an educator,” Johnston says. “In Warren, I found a lifelong friend and mentor – and I’m profoundly grateful for that.”

Gratitude is a theme among MacKenzie’s protégés. Now ceramics professionals in their own right – artists, teachers, gallerists – they describe the potter, who turned 90 this past February, almost universally, as supremely generous. And utterly modest. He leads by example, they say. They speak of his work ethic, passionate and committed. They recall visiting his home – handling his collection of pots, firing the kiln, sharing meals – and the profound impact being invited there had on how they crafted their own lives.

MacKenzie’s teaching style was deeply influenced by his own educational path. In the mid-1940s, he and Alix Kolesky, his future wife, were languishing under an incompetent ceramics instructor at the Art Institute of Chicago. A fellow student brought in A Potter’s Book, by Bernard Leach, known then as now as the father of British studio pottery. MacKenzie recalls their amazement. “It was better than anything we were doing.”

The students, inspired, began sneaking into the studio between classes and practicing the tenets of Leach’s book, which emphasized basic forms and skills. After finishing their time in Chicago, Warren and Alix relocated to Minnesota, where they were hired to teach ceramics at the St. Paul Gallery and School of Art (now the Minnesota Museum of American Art). Soon thereafter, they had a remarkably self-aware realization.

“We were lousy teachers,” MacKenzie says. Their own education was lacking; their skills weren’t up to snuff.

The young couple hatched a plan to travel to St. Ives, Cornwall, with hopes of securing apprenticeships at the Leach Pottery. Alas, the famous potter took one look at their pots and declined to hire them.

Determined not to let disappointment cloud practical matters, they asked if they could observe in the studio during the rest of their two-week trip. On the eve of their departure, Leach invited them to keep watch on the kiln overnight. “We talked about everything except pottery,” MacKenzie remembers. In the morning, Leach offered to take them on.

Asked what made Leach change his mind, MacKenzie pauses amiably. “He had a group of people,” MacKenzie says, “who had to work together.” Inviting someone in wasn’t simply a question of who could make the best pots; it was a matter of who could work together well.

And so, in 1950, they became the first Americans to apprentice at the Leach Pottery. Leach went so far as to invite the pair to room at his house. (“Bernard had just separated from his second wife,” MacKenzie explains. “And Bernard could not live alone.”) For the next two and a half years, they were treated to an immersive learning experience at home and in the studio. They studied everything about Leach, personal and professional habits alike. Toward the end of their stay, they also encountered Shoji Hamada, the influential Japanese potter and Leach’s friend. (The couple would be instrumental in organizing the two potters’ famous 1952 U.S. workshop tour with the philosopher Soetsu Yanagi.) While their pots received fierce criticism from these masters, MacKenzie insists this is how they finally learned proper throwing.

They were also absorbing important lessons about earning a living as potters. The Leach Pottery model essentially was: Make good pots, make them fast, sell them cheap. It’s an accessible philosophy, centered on everyday utility, that informs MacKenzie to this day, as he invites potters and collectors into his home, treating them to demonstrations, lots of storytelling, and the opportunity to buy pots at prices far lower than he could command.

In 1953, within a year of returning to the United States, MacKenzie was hired at the University of Minnesota, where administrators were trying to rebuild the studio arts program. That same year he and Alix bought the little house near Stillwater and began setting up a pottery studio.

“Warren brought the Leach/Hamada package to the U.S. and made it real – not by writing a book, but by doing it,” says Tim Crane, who was studying sculpture in the 1960s when he first encountered MacKenzie through fellow students and started making pots. “He figured out how to make it all work when there was no ‘living’ tradition.”

In the classroom, MacKenzie preached the importance of mastering skills. “Learning to make pots is not hard,” he would say. “It just requires a lot of practice.” What he did not ask of students was to replicate his look. “You don’t make my pots; you make your pots, and then we’ll talk about them,” he remembers telling one aspiring potter.

“Teaching someone to make pots, that’s easy,” MacKenzie explains. “But teaching them how to have an attitude to the pot, to communicate a personality, that’s more difficult.”

For conveying those more nuanced lessons, there was perhaps no greater classroom than MacKenzie’s rural Minnesota enclave. “His home in the late ’60s was an amazing place,” says Mark Pharis. “His house wasn’t grand in any way, but it was a genuine place where pots and art played a central role.”

MacKenzie never hesitated to invite students out for kiln firings, sales events, even parties. They could observe him at the wheel or watch the Leach-inspired business model in action.

“My studio is structured largely by what I observed working in his studio – his process from materials to finished work to getting the pots out to an audience,” says Guillermo Cuellar. At potlucks, MacKenzie would serve food in pieces from his collection, offering little tributes to the pots.

Linda Christianson remembers receiving a surprise invitation; a recent transplant to the area, she hadn’t even met MacKenzie yet when he asked her to take part in his annual fall sale. As an undergraduate, Pharis recalls getting a note in the mail about an exhibition, instructing him to go see some good pots: “I was amazed he knew who I was.”

MacKenzie retired from the university in 1990. “But he only retired from teaching in the formal sense,” Millfelt notes. Nancy d’Estang concurs; over the years, she says, MacKenzie has followed his former students and apprentices’ lives and careers, keeping in touch through calls and letters, offering both gentle criticism and enduring support.

And MacKenzie’s most important classroom – his home – remains. It has changed over time. For the past 30 years, he shared it with fiber artist Nancy MacKenzie, his second wife, who died in October. (Alix MacKenzie died in 1962.) The little house has become an attractive rustic-modern structure – exposed brick, vaulted ceilings, and enormous picture windows. His pottery studio is just out back, a short walk down a wooded path.

Inside the house, the kitchen island is built with module-like cubbies, each holding a different mug, many by former students – and students of former students. Pots line the top of the kitchen cabinets and crowd a hutch in the dining room. Vessels of all sizes and styles punctuate the floor. Standing in this space is a lesson in focus and single-mindedness. Says Jeff Oestreich: “The opening up of his life to us as a potter was his best teaching tool.”

Christy DeSmith is a Minneapolis-based writer. She covers arts, culture, and travel. Julie K. Hanus is American Craft’s senior editor.