Portraits in Craft

Portraits in Craft

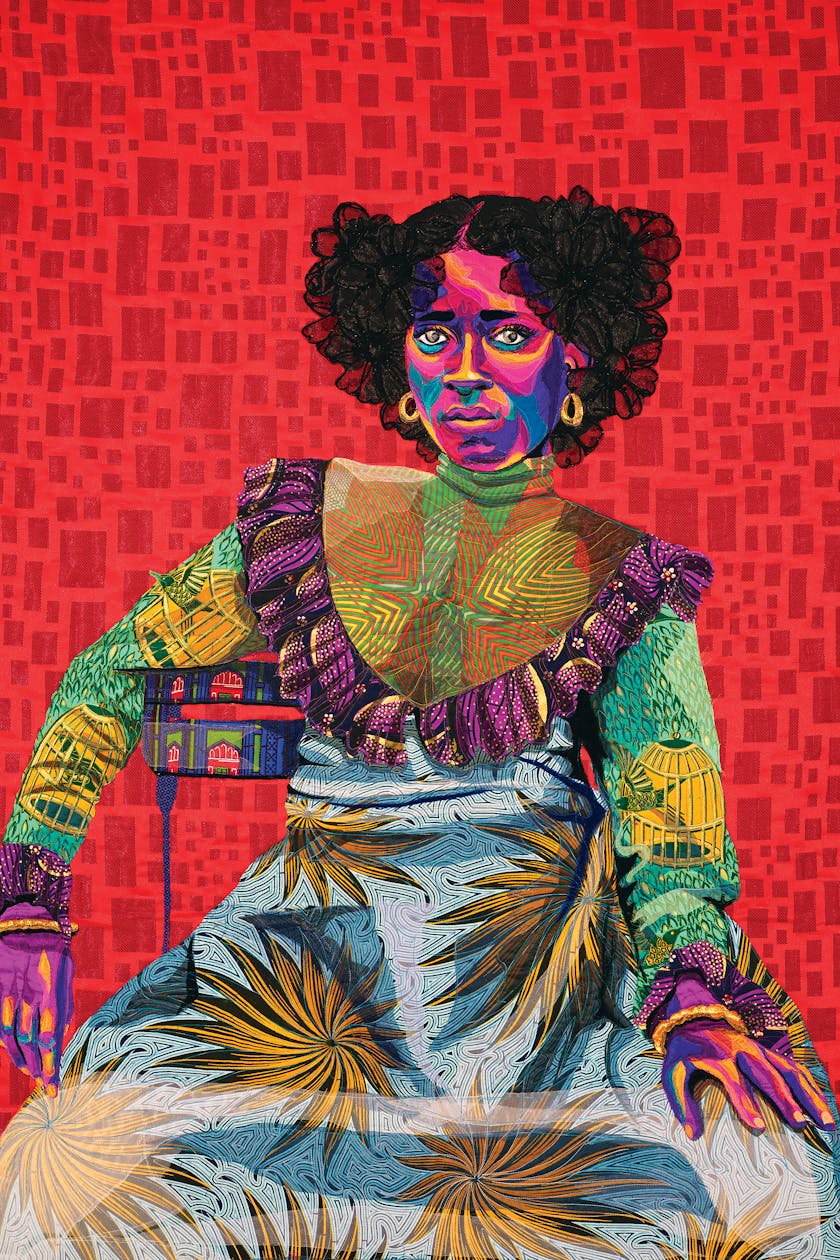

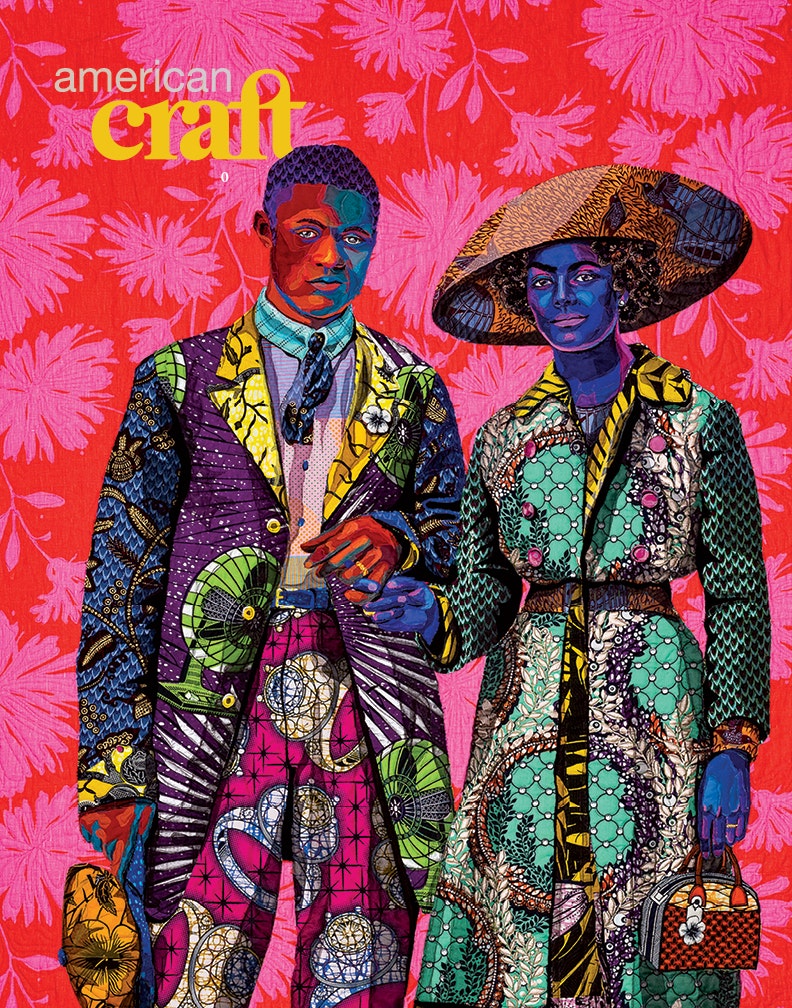

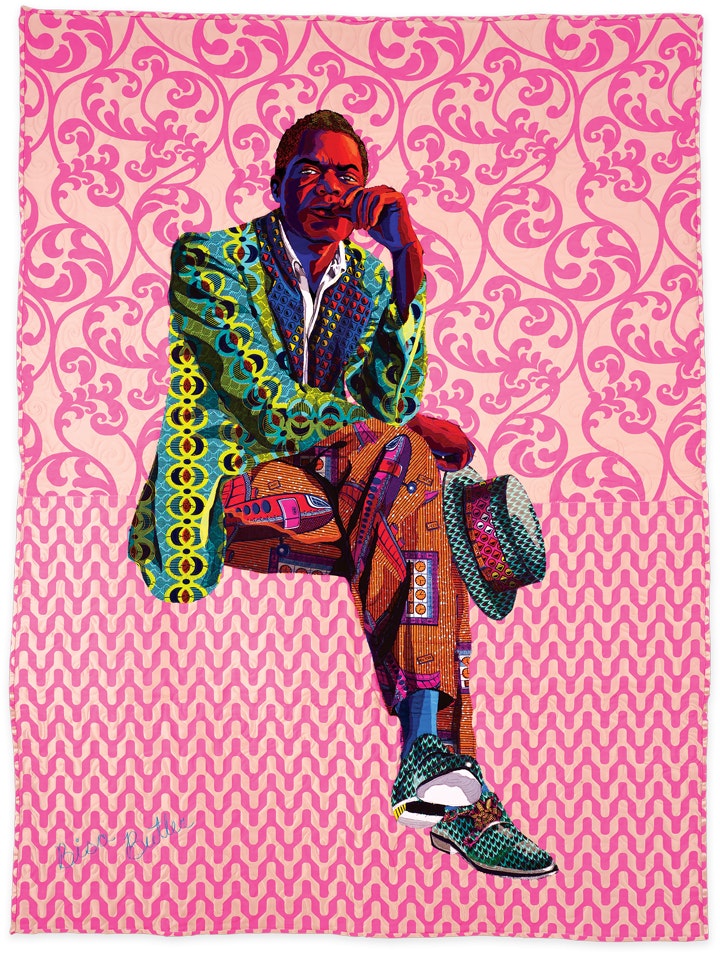

Emmett J. Scott, a journalist, educator, and author, was the highest-ranking African American in President Woodrow Wilson’s administration. Bisa Butler incorporated his image in her quilted and appliqéd piece Africa the Land of Hope and Promise for Negro People’s of the World, 2020, detail. Photos courtesy of the Claire Oliver Gallery.

We can guess at the time and place by the clothes worn and the physical setting. But look closer: Is there a spark of soul within the eyes of the sitter, an arresting gaze? Maybe the play of a smile on the lips; a slight furrow of the brow. There’s posture and body language to consider—in one photo, relaxed and open; in another, the subjects are straight-backed and guarded. These are the details that drew you to the image in the first place.

And there’s a story there, you just know it.

“I have always been drawn to portraits,” artist Bisa Butler says. As a child, Butler’s favorite activity was looking through family photo albums and hearing her grandmother’s stories behind each picture. “This inquisitiveness has stayed with me to this day. I often start my pieces with a black-and-white photo and allow myself to tell the story.”

To portrait-quilter Butler, to Chitimacha-Choctaw artist-weaver Sarah Sense, and to renowned ambrotype photographer Giles Clement, portraits are stories they tell through their craft. For Butler, found images from the past are given new life and voice. Sense’s photographic basket collages are portraits of Indigenous experiences in North America and around the world. And Clement leans into the slow process of wet-plate photography to connect deeply with each subject for the portraits he creates.

The Healer

“There is something familiarizing about the direct gaze,” Butler says. “You feel like the subject is looking at you. It becomes a two-way observation, more like a window pane than a flat, two-dimensional photo. The subject seems to look at you through space and time,” she adds, “as you do the same.”

What did they sound like? she wonders of the people she pulls from the past and into her work. What made them tick? In Butler’s work, imagining those answers is a way to tell their story.

Could the handsome man photographed in 1936 by Dorothea Lange have been a philosopher-poet and a great writer, asks Butler’s I Am Not Your Negro (2019). Four Little Girls (2018), originally photographed in full skirts and white socks on a stoop—might they remind you of the innocent Black children killed in the horrific 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Alabama in 1963?

I Am Not Your Negro, 2019, made from cotton, silk, and wool, 79 x 60 in. Photo courtesy of the Claire Oliver Gallery.

“What has been lost in our country many times is the story—the history of Black folk. The healing I want to do is to restore Black stories that have been omitted from the American narrative.”

—Bisa Butler

Butler connects strongly with portraits from the past century and a half, of Black men, women, teens, and children whose identities and stories are often lost. Some are family photographs; others are anonymous archival images from the Farm Security Administration collection in the National Archives—or, more recently, from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. “That collection was like heaven to me. There are so many high-quality, beautiful vintage photos in their archive.”

The process for translating found images into intricate, painterly, life-size quilted portraits can take hundreds of hours. Butler first sketches over an enlargement of the chosen photograph, identifying areas where she’ll apply lighter or darker tones. She prefers black-and-white photos because “it gives me the freedom to put in the colors I feel belong there.” She then cuts and layers fabric and stitches it together with “The Beast”—a 12-foot long-arm sewing machine with its own room—into a human figure appliqué based on the template sketch. The figure complete, she’ll choose a bright, often patterned backing material over batting for the background, quilting it all together in undulating allover stitch patterns. The result is a human-scale portrait that vibrates vividly with life and painterly color.

Butler’s portraits are both a continuation of and a push forward from the centuries-long history of African American quilting. Enslaved Black women, she says, would sew, weave, spin, and quilt for their enslavers’ households. After the Civil War, those women and their descendants continued to sew and quilt, often using scraps or whatever they could find. Butler’s mother and grandmother also sewed when she was growing up, and it was for her grandmother that Butler created her first portrait quilt. Butler’s mix of atypical quilting materials (lace and chiffon, for example), along with brilliant hues and the rich patterns of African textiles, pays homage to this deep history.

Lately, she’s been pulling images from the archives of Howard University, her alma mater, into a new series. “I want the wider world to understand why HBCUs [historically Black colleges and universities] graduate more Black doctors than any other universities in this country, why we call Howard the ‘Mecca,’ [and] how rich and unique Black campus life is.”

Butler’s portraits aren’t just her contribution to the quilting tradition. They are also a subversive act. By combining quilting with the Western art genre of portraiture, she forces the fine art world to change how it sees the craft of quilting.

Rather than elevate her subjects, Butler says she depicts just what she sees. “I believe in humanity, in us,” Butler recently explained in FAD Magazine. “I see something in them that I find beautiful, and I am just amplifying that for the world to see.”

To honor Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley, who were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in a church bombing in 1963, Butler used an image of girls in Four Little Girls, September 15, 1963. Photo courtesy of the Claire Oliver Gallery.

Butler says she sees each subject as her extended Black family and wants to do right by them. “What has been lost in our country many times is the story—the history of Black folk. The healing I want to do is to restore Black stories that have been omitted from the American narrative.” What began as a work to comfort her beloved grandmother continues as a practice of healing: “Hopefully my quilts can heal some of the wounds of historical neglect.”

The Searcher

“I want my work to feel alive,” Sarah Sense says of her woven photo collage and mixed-media work. “Like a Chitimacha basket might hold water, my baskets hold ideas. They hold time and thoughts and memories—the past, the future, and present, even. They can hold people, too.”

Her patterns are all traditional designs, recreated from her collection of Chitimacha and Choctaw baskets, combined with what she’s learned from Chitimacha basketweavers. With the blessing of the tribe, Sense has spent years reinterpreting Chitimacha basketry into her unique contemporary collage work. Printed photos cut into strips take the place of the river cane traditionally collected from Louisiana’s Bayou Teche.

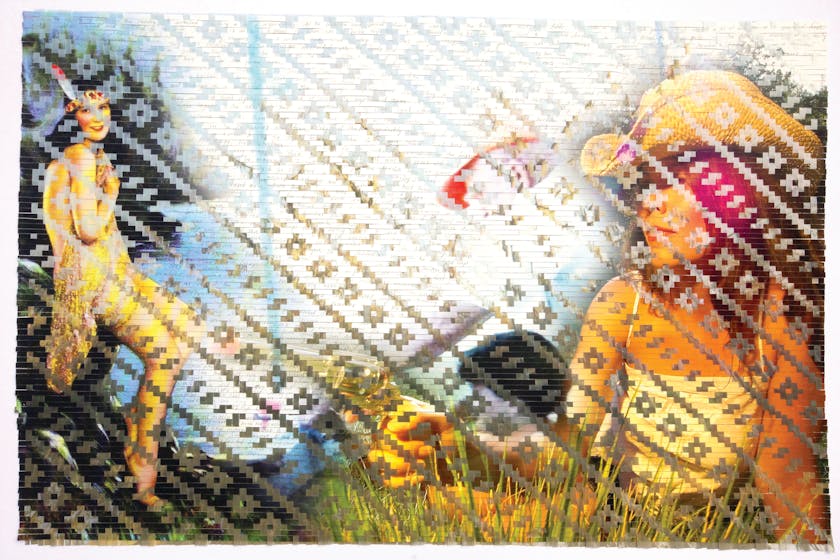

Sarah Sense says that her Cowgirls and Indians series is broadly about “the oversexualization and colonization of Natives and female bodies.” Here, in Grandparent’s Stories, 2018, the Indian princess is from an antique poster Sense found in Orange, California, and the cowgirl on the right is Sense with a toy gun. Photo by Sarah Sense.

Sense, like Butler, looks for photographs and images that spark questions. “My responsibility, or gift, as an artist is to look at an image differently,” she says. “I’m not a scholar; I don’t have to look at it with an academic filter unless I want to.” It’s less important to think of herself as a researcher, she says, than as a searcher of stories that have been lost.

Sense pulls together a variety of visuals—vintage movie posters from the old cowboys and Indians genre; historic photographs of Native peoples, elders, leaders, and prominent figures; photos that she takes on her travels; documents such as historic maps, and more—into a digital photo collage in Photoshop. She prints these composites on bamboo and rice paper, including custom-made bamboo paper by a Thai artisan. The plant’s relation to the river cane of the Chitimacha, she says, is a nod to her connection with the broader Indigenous community around the world.

Sense combines silk screens and photographs for her Weaving the Americas work in Santiago, Chile. Photo by Francisco Granados.

“Like a Chitimacha basket might hold water, my baskets hold ideas. They hold time and thoughts and memories—the past, the future, and present, even.”

—Sarah Sense

Once printed, the image is cut into strips to become her weaving material. She then interweaves these images into each colorful, geometric “photo basket,” incorporating layers of paint, drawing, or wax, along with personal writings and excerpts from her Grandma Chillie’s memoir.

Cycles of deconstruction and reconstruction play out in the content of Sense’s work, too. Her Cowgirls and Indians series (2018) and the earlier Cowgirls and Indian Princesses series (2004–2008) examine the harmful stereotypes of Native people in the western film and television genre, juxtaposing pop culture imagery with lived Native experience. In Lone Ranger and Tonto with Buffalo Bill and Sitting Bull (2018), the screen duo and the historical figures are interwoven with the landscape of the Bayou Teche, home to the Chitimacha.

For Sense, weaving is a dialogue—there’s a constant push and pull in how much of each image she brings into the foreground or background. It’s a conversation, she explains, about Native identity in a broad sense and one she conducts internally too. Increasingly, Sense’s works are self-portraits and explore her identity as a mixed-Indigenous woman, mother, American, and global citizen. In a 2004 artist statement, she wrote, “I was raised in California with a strong influence of Hollywood idealism. Popular culture has given me false ideas of ethnicity and what it means to be a female.” Sense’s practice seeks more authentic answers.

Choctaw Irish Relation 9, 2015—made with bamboo paper, rice paper, pen, ink, inkjet print, wax, and tape—includes a 1952 photograph of Sense’s mother and grandmother, text from her grandmother’s memoirs, and photographs of Ireland. A Photo by Sarah Sense.

In her newly built studio in Sacramento, California, where she has settled with her young family, Sense is working on a huge piece for Florida State University. When she can, she also hopes to get back to a series for the British Library that incorporates colonial-era maps of tribal territories before the founding of the United States.

sarahsense.com | @sarahjewellsense

The Traveler

Photographer Giles Clement has only just hit the road again since the nationwide coronavirus lockdown. Before spending nearly a year stationary, Clement could be found toting the huge large-format-view camera he built, as well as his mobile studio and darkroom kit, to events around the country—all to practice a technique from 150 years ago.

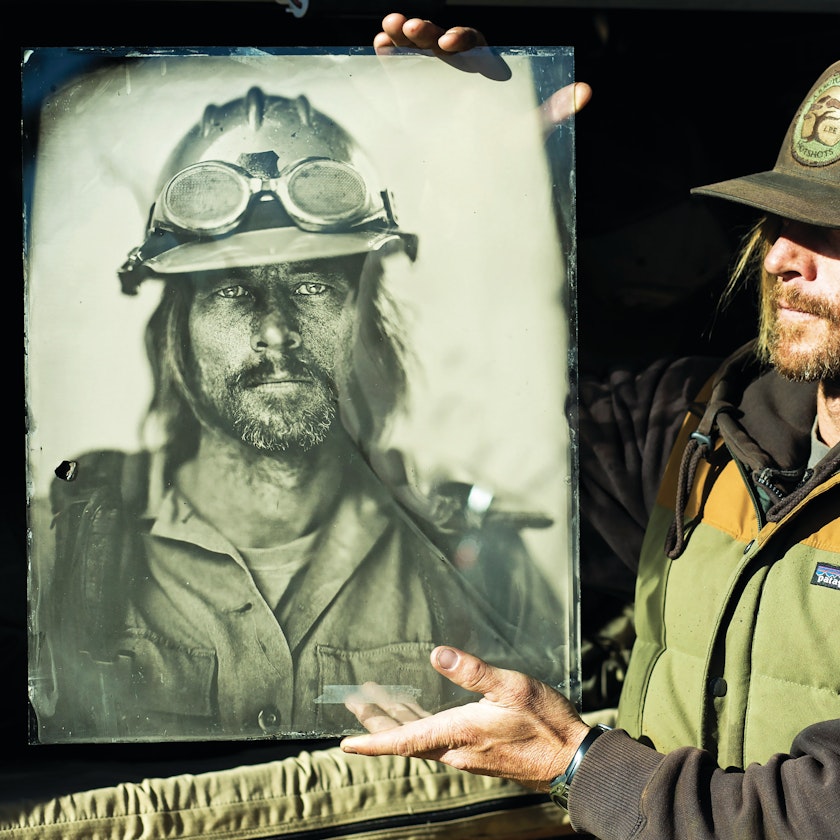

Wet-plate photography is a labor-intensive process often associated with portraits of Civil War soldiers, leaders, and battlefields taken by early photographers such as the Union Army’s Matthew Brady. A plate of glass (for an ambrotype) or tin (for a tintype) is taken into a lightproof space and coated with an iodized collodion and then a silver nitrate solution, making the plate light-sensitive. The plate must then be exposed through the camera within about 15 minutes because its light sensitivity weakens as the plate dries. The result is a single unique image on an object you can hold in your hand.

“It’s a slower process . . . and in that time you really connect with the sitter.”

—Giles Clement

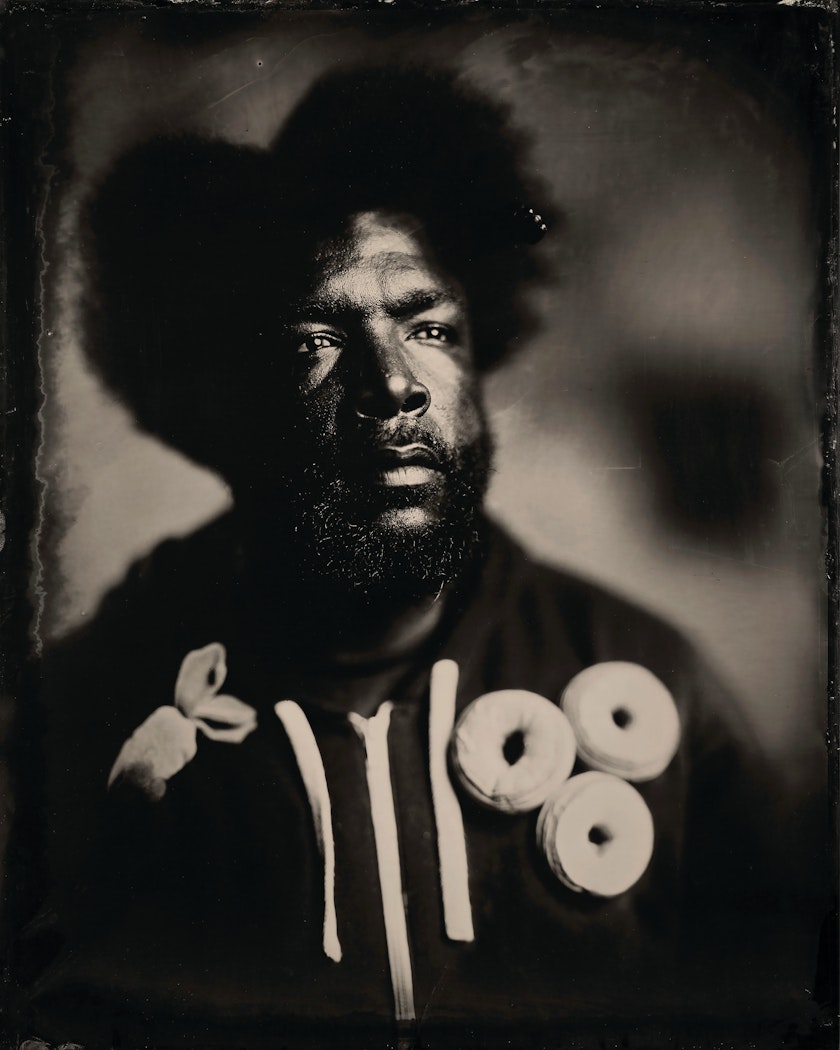

Always exploring the limits of his craft, Clement made headlines after taking the first known tintype from a drone, but he’s best known for his large-format portraits. Clement’s ambrotypes of musicians and performers at New Orleans’ famous Jazz & Heritage Festival, including celebrities such as Nick Offerman and Questlove, practically glow with inner life. Part of it is the medium: ambrotype and tintype portraits are our mirrored image, so the portrait (at least to the sitter) captures the more familiar version of ourselves. It also picks up fine skin and hair texture; blue eyes take on an eerie paleness. And since light is captured in a silver chemical compound over glass or metal, every portrait is luminous.

Since 2020, Clement has forayed into digital photography, but he says, “Working with ambrotypes has taught me certain methods of engaging with my subjects. It’s a slower process versus digital, and in that time you really connect with the sitter.”

Ben Holmes, a hotshot firefighter in California, holding his ambrotype portrait by Giles Clement. Photo by Giles Clement.

Taking the time to empathize, to be open, he says, is what results in deeply personal images. It isn’t enough to make a good image, he adds. “Photography, perhaps more than other art or craft, is so accessible now that anyone can take a technically good photograph. But technical skill alone is not worth anything. It’s what you do with it. It’s the connections that show through the image that make it worthwhile.”

gilesclement.com | @gilesclement

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.