Push and Pull

Push and Pull

Urban Glass, the Brooklyn-based collective Jamie Harris has called his artistic home for the past decade, closed for renovations in 2011. While the organization completes work on its new state-of-the-art facility (due to open this year), the crew has been working out of a cramped temporary space. That’s ironic, because Harris’ work keeps getting bigger – in size, yes,

but also in ambition.

While a dozen students listen to a lecture in the classroom section of the makeshift studio, Harris shows off some works in progress. There are heavy discs in mirrored glass, intended for a wall-mounted triptych, and two dozen purple bulbs for another installation, all resting on a worktable while the mounting brackets dry.

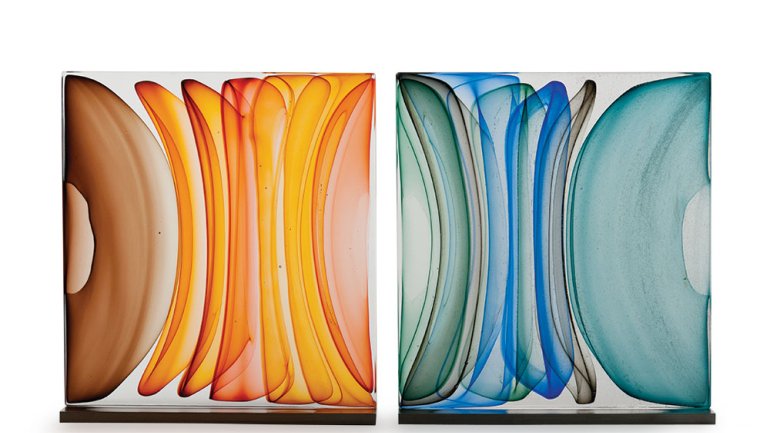

Then there is the work that’s big in another way: one of Harris’ Incalmo Orb vessels, a vase-like piece, perhaps 18 inches wide, which resembles something Mark Rothko might have made if he’d apprenticed to an early 20th-century Italian glassmaker. More breathtaking still are two blocks of clear glass, about 2 feet square and 2 inches thick, in which liquid colors play cat-and-mouse across the silicon canvas or collapse into themselves.

But beauty isn’t all that he’s after. “I’m so interested in how I can use color in glass sculpture in a way that can be emotionally evocative, even if it’s abstract,” Harris says.

It’s an interesting time to be working in glass, observes Harris, 38. The material was invented thousands of years ago, but wasn’t adopted as a sculptural medium until the middle of the 20th century. Today, glassmakers like Josiah McElheny, who has been collected by the Museum of Modern Art, are gaining widespread acceptance. “It’s a new art form with a 2,000-year history,” Harris says.

As a freshman at Brown University, Harris approached a glassmaker named David Van Noppen at a street fair in Providence, Rhode Island, and talked his way into an unpaid apprenticeship. After graduating in 1997 with a degree in comparative literature, Harris went to work for Van Noppen as a studio assistant.

At first, “I didn’t think it was a career,” he says. “I just thought it was something to do for a year with my lit degree.” Soon, however, he was hooked – and started studying at America’s glassblowing meccas, including Pilchuck, Penland, and the Corning Museum of Glass, taking workshops with people such as McElheny, Dante Marioni, Benjamin Moore, and the Italian master Lino Tagliapietra.

In the early part of his career, Harris was engaged in the glassblower’s pursuit of traditional technical conceits. “You learn to make a round thing, then you want to make it rounder and straighter and thinner,” he says. “My early work was obsessed with excellence in craftsmanship.” His distinctive aesthetic began to emerge when he moved to New York at the tail end of the 1990s and started working at Urban Glass.

In addition to the usual array of glassmakers and students, the studio was populated by New York art scene stars like Robert Rauschenberg and Kiki Smith – painters who wanted to incorporate glass into their work, but weren’t necessarily interested in learning to work with the material. Harris sometimes blew glass for them; the experience taught him “to move from idea to execution,” he says.

In the years that followed, his work shifted from technical pieces to more playful expressions of the traditional glassmaker’s tool set. His Mod series – brightly hued, blown and carved glass – alludes to traditional Italian wheel-cutting, he says, but here carving exposes layers of color and alters form. His sleek studio line also bears witness to his modernist approach.

But the work “is still based on glassblowing,” Harris notes. “It’s the love of the process that’s centered my interests.”

For years, he’d been attracted to the color sensibility of artists such as Kenneth Noland and Ellsworth Kelly. Then he decided to press beyond opaque colors and begin playing with translucence. “I wanted to capture that flowing sense of color and movement I see in my work when glass is 2,000 degrees,” Harris says.

He developed his Infusions during a recent residency at Corning. Harris was already using a technique called Swedish overlay – rolling one bubble of glass over another, like rolling a sock onto a foot – to combine colors for his Incalmos, which play off an Italian style of design built in three bands of color. To build his Infusions, he combines bubbles of glass, but instead of sculpting the hot matter into vessels, he puts it in molds and lets it cool in a kiln. Then he brings the heat back up and lets the glass slowly melt into the form’s corners. The results are paintings done in glass.

As for what’s next, Harris isn’t sure. He’s neither an emerging nor an established artist, he says, and he’s comfortable working in the space in between. Right now, he spends about half of his time working on commissions, creating art for collectors, but also makes more functional objects like custom lighting. (For all his artistic achievements, Harris says his mother didn’t come to grips with his career choice until he made his first work for Tiffany’s.) The rest of his time, Harris creates unique pieces destined for exhibitions such as the International Glass Festival in Sofia, Bulgaria, and the SOFA show in Chicago, both of which showed his Infusions last year.

Whatever is next, it’s likely to be bigger – in size or concept. Lately he’s been thinking about how he can take his Infusions to a larger scale, Harris says, arranging the square blocks as installations. “How can you take multiple elements and put them together in a way that’s transformative to a space?” he asks. “A chandelier or an installation, they both eat space, so hopefully they eat it well.”

Patrick Clark is a writer in New York.