Read. Roar. Repeat.

Read. Roar. Repeat.

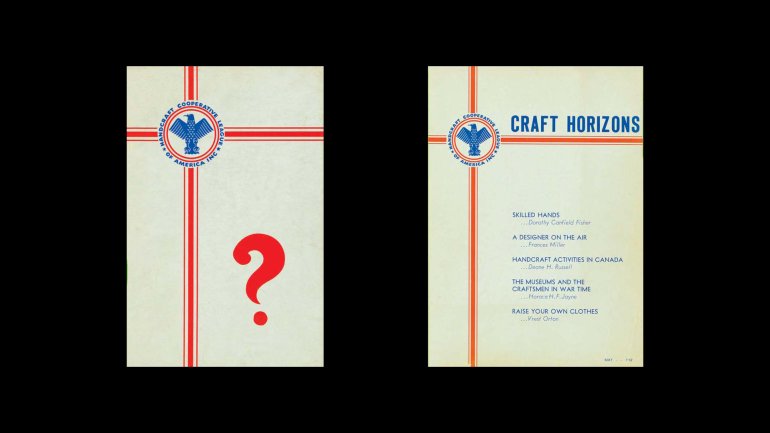

The following letters appear in the September/October 1958 issue of Craft Horizons, forerunner of American Craft. On one tidy page, you can see the diverging opinions that editors deal with – a pleased reader, another who alternates between contentment and seething indignation, and one who’s had her fill. (And not just anyone, but legendary ceramist Marguerite Wildenhain.) Who knows how Conrad Brown, the editor at the time, made sense of it?

Sirs: Each issue gives me great pleasure and information. Such a publication was badly needed, and I congratulate you on the standards you maintain. Ray Faulkner Head, Dept. of Art & Architecture Stanford University, Calif.

Sirs: Every issue of Craft Horizons is interesting and informative, however controversial the subject matter. As often as I may seethe with indignation at something I particularly dislike, there is always something else of extraordinary interest to make up for it. Mrs. L.B. Grimes San Francisco, Calif.

Sirs: Would you please cancel my subscription. When the level of your publication will rise again to an interesting magazine, I shall subscribe again. M. Wildenhain Guerneville, Calif.

You see a lot of curious discord when you review 75 years of letters to the editor.

You also see the amazing, sometimes hilarious, evolution of American expression. Over the years, formally worded missives (does anyone say “missive” anymore?) give way to casual Facebook kudos and gripes. Terms like “groovy” and “far out” sneak into letters in the 1960s. By the time of the 2007 American Craft redesign, comments are blunt and unsparing, perhaps mirroring the no-holds-barred communication on the web today.

But the disagreements you see in 75 years of letters to the editor of the American Craft Council’s magazine, whether decorous or rancorous, tell a bigger story. Readers take issue – with the magazine’s writers, with other readers – as a way of coming to terms. As they reacted to articles and images, as well as to developments in what became the 20th century’s “craft field,” they had an implicit goal: hashing out the essence of craft.

Specifically, they were debating the relationship between craft and art. As they responded to stories that reflected the impingement of modern and postmodern art on craft, between the lines, they were posing questions: Should craft stay true to its traditional functional roots? If it doesn’t, is it still craft? Should craft emulate art (itself a nebulous, ever-changing field)? What does it take to be recognized by the art world? Is that even a worthwhile goal? And later: Craftsmanship and skill don’t matter to art; do they still matter to craft?

“A specter haunts the craft world of America,” wrote critic John Bentley Mays in a 1986 commentary that touched off a landslide of angry notes – “the specter of art.” Art has long haunted craft, and you can see it in the letters.

THE EARLY YEARS

1941 – 1959

Letters to the editor in the magazine’s nascent years, when there were several editors, including ACC founder Aileen Osborn Webb, included polite skirmishes about whether fly-shuttle weaving could be considered handweaving (1945), whether the magazine was too casual in its precautions about working with lead (1946), and whether a ceramist designing tiles for manufacturing, with no hands-on involvement in the making, could still be considered a craftsperson (1946). (“The comments offered in the article give my eyebrows a bit of a lift,” one genteel letter writer protested.)

Then, in 1957, came an eruption – the sort of complaint that would surface again and again over the next decade. For the third time in three years, an already controversial ceramist had judged a competition and favored his own students. The anonymous correspondent, writing in the May/June issue, had had enough:

Sirs:

The greatest example of complete juror bias occurred with the announcement of the winners of the Fifth Miami National Ceramic Exhibit of which Peter Voulkos was one of three juror members.The listing of winners as Paul Soldner, John Mason, Kenneth Price, Bill Bengston, and Jerry Rothman came as almost no surprise to us in Los Angeles. They are all students of Peter Voulkos, teacher of ceramics at the Los Angeles County Art Institute. . . .

Peter Voulkos’ students cannot be the only ones producing award-winning ceramics, and one even wonders if their work could be classed as good ceramic ware, considering . . . they are but pieces badly thrown, badly glazed, and badly crafted.

Name Withheld on Request

The writer is frustrated with nepotism, of course, but the letter also suggests something else: an uneasiness with the sculptural sensibility creeping into craft. Suddenly work that didn’t follow the rules – of functionality, of technique – was being rewarded, which did not sit well with many readers. (Voulkos remained a divisive figure to Craft Horizons readers; a 1966 letter writer called him “vulgar,” “publicity-hungry,” and a “monstrosity.”)

Letters about jury bias continued to trickle in over the next few years. (In 1959, a letter writer composed a funny 12-stanza poem on the subject.) In September/October 1959, ceramist Dora De Larios scolded her fellow makers. “Why is it that after every major show there is such a fit thrown by some craftsmen? So Peter Voulkos, John Mason, Larry Shep, and Henry Takemoto received the prizes. Good for them!” If the fit-throwers worked harder, she added, “they might begin to give competition to the winners that they are now being so petty in tearing down.”

THE SLIVKA YEARS

1959 – 1979

Rose Slivka came to her role just as an American craft movement was coalescing in the United States. Slivka’s goal was to raise the standards for American craft, and the articles, some of which were quite provocative for the time, were aimed at makers.

Raising standards is not a simple proposition, of course. And in Slivka’s issues, you see readers continually wrangling about quality and jurors’ role identifying it. Craft Horizons served as a forum for anyone who had anything to say about craft. In November/December 1963, that somebody was another polarizing ceramist, Robert Arneson.

“As a member of the 1963 California State Fair craft jury, I wish to make known that censorship was imposed on this exhibition by its directors,” he began. A prize-winning leather and ceramic pot by Charles McKee had been removed from the show without the consent of the jury. What’s more, one of Arneson’s own pieces had been removed “because of its ‘assumed’ offensive nature,” he wrote.

He dismissed most of the work in the show as “safe art and dull mediocrity” and called for a government investigation into the directors’ actions. For the big finish, he argued that if the directors didn’t want the best art, “the available space might be better used as a honky-tonk corral.”

Jurying was a flashpoint, and mystery shrouded judges’ choices. In a first-person account in 1965, weaver Dorian Zachai explained how she made decisions as a juror. “I look at things with my insides – and that is all there is to it,” she explained.

Reader Jack Cloonan knew a softball when he saw one. “For those who would look at things with their insides,” he wrote in the May/June issue, “may I unfacetiously suggest that looking with one’s eyes precludes any possibility of ending up inside-out.” It was one of many responses to her manifesto.

Slivka may be best known for a 1961 feature that set the tone for the turmoil of this era. In the July/August issue, she advocated eloquently for the new sculptural aesthetic in ceramics, calling it uniquely American. She saw in work by renegades such as Voulkos, Arneson, and Harold Myers (whose pictured sculpture had the perhaps unfortunate title Big Pile) a restless, noble search for identity. She lauded “the US craftsman, a lonely, ambitious eclectic.”

The essay unleashed an avalanche of comment that reads like a who’s who of midcentury craft. (It remains an important reference for the field.)

“It is difficult for me to tell you how much I admired ‘The New Ceramic Presence,’ ” wrote enamellist June Schwarcz, “how much I have felt the need for such an article, and how well I thought it was written.” Alfred University ceramics professor Daniel Rhodes called it “extremely interesting,” reflecting “a lag between the ‘fine’ arts, where the ideas seem to start, and the ‘crafts,’ where the ideas crop out anywhere from 10 to 30 years later.”

But many from the functional community were not amused. “Quit corrupting the young generation with your fake double standards,” wrote Marguerite Wildenhain. (Wait, didn’t she cancel?) “Nobody in his senses can continue to subscribe to Craft Horizons, supposedly the magazine of the ACC, without blushing with shame or getting blue with fury.” (Fourteen years later, she declined her nomination to the ACC’s College of Fellows, citing its “horrible magazine.”)

Then there was the priceless response of Warren MacKenzie:

For the longest time we had thought that the “Big Pile” in our neighbor’s cow pasture was good only for enriching the fields. Now we find that if you can pile it high enough with the written word, or in the visual fields, it can pass for art. In the future, we will give up any attempt to make functional ceramics as an expressive form since, apparently, “Containers … make almost no demands on our sensibilities, leaving us free” – free to concentrate on getting the cows to cooperate for higher and larger works of “ART.”

Next on the firing line was Slivka’s 1963 essay “The New Tapestry,” featuring unconventional fiber works by “look-with-my-insides” Dorian Zachai, Claire Zeisler, Sheila Hicks, and Lenore Tawney.

Katharine and Harry Manning were indignant. “I trust that in the future you will not publish such atrocities on weaving. . . . In our weaving studio-workshop, we keep this issue hidden from the students,” they wrote.

Slivka took the heat and kept going. An early 1969 issue featured plastics and pop art. Lotte Streisinger predicted dire consequences:

The pages of your magazine are icky-bristly with pictures of plastics, machinery, mind expanders, thingamajigs, and weirdo nihilistic clay objects. . . . If the craftsman does not uphold the enduring values of humanity and the works of the human hand, who will? And if nobody does, we are lost, lost, lost. . . . Which side are you on, the side of pop-groovy-bullshit or the side of humanity?

A year later, the magazine covered the work of Robert Arneson, spurring a tsunami of criticism that continued for years. Readers called it “sick,” “pornographic,” and “juvenile.” Valera Lyles clearly enjoyed skewering David Zack’s writing:

Were it not for your article, I would still view Arneson’s ceramics as a nasty little boy’s vulgarity rather than brilliantly searing, iconoclastic social comment. Now, joyously liberated and suffused with new insight, I am off to the bus depot restroom in search of yet another monument to man’s unquenchable creativity and majestic search for truth.”

David Smith wasn’t buying it either: “Now that we have had a good, long look at the emperor’s new clothes, we begin to see a naked ass.”

Slivka’s era was tumultuous, and it dramatically shaped what was now a bona fide field. She led craftspeople – many kicking and screaming – beyond the old perimeters to a realm where craft mingles with art.

In her farewell to readers of Craft Horizons in June/July 1979, Slivka reflected on how the field had changed during her tenure:

Twenty years ago, when we were all young in the crafts, we were a small, intimate, talky group. . . . We have grown from a group to a movement, from being a unified assemblage of friends to being a diversified population of people who know each other and people who don’t know each other, many strangers, many friends, and even some antagonists, going in many directions and with a multitude of needs. This is a new time.

THE MORAN YEARS

1980 – 2006

And a new time it was. In the six-month gap between Slivka and her successor, Lois Moran, the magazine changed its name to American Craft, added new departments, and redesigned. Plenty of readers liked the changes; Helen Garfolo called it “less pretentious” and “more genuine.” But naturally there were detractors, including Daniel Rhodes, who called the new name “a repudiation,” “a great mistake,” “chauvinistic and provincial.” Paging through American Craft, he said, “I felt almost a sense of shame at being identified with the craft scene. The shallowness of the writing, the lack of substance, the slick House & Garden layouts all contribute to an overall effect of cheapness and triviality.”

The new professionalism of the magazine – and efforts to broaden the conversation beyond makers – made many readers nervous. But within a few issues, Moran appeared to win over craft insiders. Like Rhodes, metalsmith Ron Hayes Pearson had worried that the redesigned magazine would be a “gaudy People-type publication that visually and verbally glamorized crafts,” but his April/May 1980 letter lauded “the trend toward greater depth.” In the same issue, scholar Janet Koplos praised the addition of “lots more informational meat” to the content.

It’s possible that Moran learned from the beating Slivka took; she published fewer letters in her 26 years. But then-senior editor Beverly Sanders says the staff in fact received fewer letters. Perhaps the natural expansion of the field – the addition of gallerists, curators, and collectors to the audience of artists and teachers – had a pluralizing, stabilizing effect. Maybe the community had survived what group development psychologist Bruce Tuckman calls the forming, storming, and norming stages, and settled into performing. Maybe the tribe was becoming the establishment.

Not that there weren’t controversies in Moran’s time. In 1985, W. Hankinson objected to a Therman Statom sheet-glass work on the previous issue’s cover (Oct./Nov. 1984). “It looks like a reject from a first-grade glue session. I’ve found better-looking art in the local city dump,” Hankinson wrote. Moran defended the choice in an editor’s note, pointing out that Statom had been included in an important recent exhibition, was a lecturer at UCLA, and had received a $25,000 NEA grant. Potter Dick Woppert took exception to Moran’s defense. “To justify [Statom’s work] on the cover because the artist won $25,000 from a fellowship is offensive,” he asserted.

Probably the biggest flap of Moran’s tenure began in December/January 1986, with the publication of an essay by Toronto art critic John Bentley Mays explaining why art critics don’t pay much attention to contemporary craft. Craft artists, or as he called them, “artisans,” do not get “validation, exposure, and recognition” from art critics because, simply put, craft is not art, Mays wrote. Fine artists, he explained, are “moved by skepticism and science, not by old-fashioned pieties.” Modern art, he wrote, is “anti-hand” and “anti-craft,” and the process of appreciating it is different. “Modern art yields up its complex, ironic truth about the world not in being handled and known intimately, but in being contemplated by the educated eye.”

Readers went nuts. It took several issues to publish the objections. Art historian and gallerist Theo Portnoy called Mays’ piece “a chore, so pretentious, so verbose and grandiose.” O.J. Bergeron got more personal: “Obviously he won the Canadian National Newspaper Award for criticism based on the size of his testicles and not his ability to validly judge art.”

Mary Byington confronted Mays directly: “Working with materials keeps us craftspeople honest, human, and quite discerning about quality. When you want to really understand art, make something. For now, to the trash heap with your words and ideas.”

In the rancor over Mays’ high-handed dismissal of craft, you see a central preoccupation of the Moran era: the desire of craft artists and allies – curators, collectors – to be acknowledged by the art world. Along with that came a new resolve to pay the dues necessary, if not sufficient, for acceptance – to document works, to know craft history, to formulate craft theory. To do as the art world does.

This resolve is clear in the letters responding to Robert Kehlmann’s dispassionate takedown of glass collectors George and Dorothy Saxe in the April/May 1987 issue. In a review of an exhibition of their collection, Kehlmann observed that collectors of glass – perhaps the most seductive craft medium – “have often failed to exercise the rigid scrutiny in looking at glass that is routinely applied to other two-dimensional and three-dimensional works of art.” Reaction was mixed. Michael I. Brillson defended the Saxes’ investment in glass artwork. Al Shands congratulated Moran “for giving the writer the freedom to call the shots” as he saw them.

Bruce Metcalf continued the call for tough, independent craft criticism in eight pages of almost solid text in 1993. In the February/March issue’s “Replacing the Myth of Modernism” – 10,000 words, not counting footnotes – Metcalf argued that what craft had borrowed from modern art – a disinterested way of viewing and describing objects – had robbed it of its valuable roots in utility, in everyday life, in physicality. Don’t envy the art world’s cerebral detachment, he urged. But don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater; don’t be vacuous. “The paucity of thinking and writing on craft has led to a vacuum in debate and standards,” he lamented.

Response to Metcalf’s opus was measured, certainly lacking the passion of the Mays letters. Maybe that’s because Metcalf is a jewelry maker as well as a critic; he wasn’t some snooty outsider. One of the most articulate and extensive responses came from furniture maker Joshua Markel, who argued that “rather than beat the long-dead horse of modernism, [Metcalf] really should be running, stick in hand, after mannerism.” He blasted the craft world for “the pursuit of the odd, the quirky, the distorted, the strangely proportioned,” for “the rejection of function and technical accomplishment in order to rub shoulders with the art world.”

Dulcimer maker Nicholas Blanton praised “Metcalf’s postmodern postmortem and his images of us poor craftspeople pressing our noses to the windows of fancy art galleries, wistfully looking at price tags.” But his parting shot took aim at the field’s burgeoning academic wing: “You MFAs got yourselves into this Just-As-Good-As-Art quandary, and you can get yourselves out. We’ve got work to do.”

As Moran’s time wound down, the debate continued: Should craft keep chasing after big brother art, seeking acknowledgment and approval?

Critic Deborah Norton’s answer, in a 1999 review of a London basketry exhibition, was a pragmatic yes. “Some may resent the idea of presenting craft with the primary aim of appealing to the art world,” she wrote. “But if, as appears to be the case right now, museums, galleries, the media, and financial powers-that-be all seem to favor fine art, craft must learn to play the game in order to get the recognition it deserves.”

No way, responded longtime American Craft contributor Jody Clowes in a February/March 2000 letter. Art is a bully to be confronted. “The paradigm of artistic hierarchy so deeply rooted in Western elite culture . . . will retain its power unless it is actively and consistently rejected by those who care deeply about objects made for use as well as contemplation.”

THE WAGNER YEARS

2007 – 2009

Lois Moran retired in December 2006 at the age of 73, after one of the longest tenures of any American magazine editor. If the transition from Slivka to Moran seemed dramatic, the change from Moran to Andrew Wagner was breathtaking. The 30-something Wagner came to American Craft from Dwell, a stylish consumer magazine about architecture and design that he had helped found.

For almost three decades, Moran had hosted a mannerly dialogue of tastemaking artist profiles and sober exhibition reviews. Wagner burst through the door and changed the subject. The redesign he launched in October/November 2007 announced the new era with colored text, a cover flap, inventive display typography, a detachable gallery and studio map, long lists of URLs (he also launched a magazine website and blog), and an emphasis on topicality (the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, for example). The cover featured a tight portrait of DIY artist Nathalie Lété. The cover story was 10 pages of photographs inside her Parisian loft; there were captions, but no other text.

Moran’s sedate gallery opening of gray heads sipping Chardonnay had morphed into a Renegade Craft fair.

Wagner stayed less than three years, and much of the feedback he drew concerned the redesign. Readers were split. Ceramist James Aarons was thrilled: “From bicycles to water towers to studio makers, this issue commemorates the brilliant and broad wonder of the craft (art) world.” Nina Graci relished the magazine’s new “joie de vivre and that of the artists featured” and was relieved to see less vitality-sapping “curator-encumbered copy.”

Frank Schueler, on the other hand, demanded that Wagner “clean up the magazine or resign.” Jon Ryan and Tim Hill disliked Wagner’s emphasis on artists as quasi-celebrities; they missed the longstanding, formalist focus on artworks. “I would prefer to see a piece of artwork rather than the artist,” Ryan wrote.

Wagner ruffled feathers with the artists he profiled, too, perhaps channeling his inner Arneson. In April/May 2009, American Craft published a story on London designer Virginia Gardiner, who uses horse manure to make vessels and sculptures. Here’s a passage:

Her palm-sized dodecahedron Poo Gems may have the consistency of a seed-based chewy snack from Whole Foods, but they are certainly not meant to be eaten. “I had a technician at my college sizing one up in his hand and asking, ‘What is this?’ ” Gardiner says. “He just put it down very gently when I said it was shit.”

Lucia Kimball and Sharon Barette were among those who fumed. “The magazine does not showcase the quality of art and craft I have come to expect through the years, the article ‘In Praise of Poop’ being a prime example,” Barette wrote in June/July. Kimball was grossed out by the inclusion of excreta and creeped out by another story on insects as an art material.

Wagner’s rebuttal – a form he perfected as editor – is longer than either letter on “Poop” in that issue. It concludes: “While we can certainly understand your distaste for the work, we stand by our belief that it is important to consider it.”

What drove Wagner? It wasn’t necessarily a particular viewpoint on craft’s proper relationship to art. In any case, with his brash approach to content and design, he stuck a thumb in the eye of the craft establishment. Then he blew town.

THE INTERREGNUM

2009 – 2010

Janet Koplos filled in as guest editor for four issues after Wagner left, injecting some historical scholarship into the magazine. In a striking post-Wagnerian touch, the August/September 2009 cover reads: “A Century Ago, Omega Workshops Led British Artists to the Applied Arts.” The issue also includes an essay on why Boston was such an important craft incubator, birthing the Society of Arts and Crafts in 1897.

Koplos knew how to strike a nerve, though. The cover for October/November 2009 may be the most criticized in the magazine’s 75 years. The tight shot of Lauren Kalman’s gold-encrusted tongue, dripping saliva, introduced eight pages of body “embellishment” inside. In his article, writer Gabriel Craig called Kalman “the child of art and craft’s divorce” and praised her work as “both desirable and disgusting.”

By now, readers were accustomed to artists who brought arty, unsettling concepts to their work with craft materials; but most weren’t ready for this. Robert O. Fisch responded: “Lauren Kalman’s so-called art pieces like Syphilis are nothing more than tasteless attempts to attract attention.” David Bryant called it “self-loathing gone public.” Marlene Cole demanded “a retraction and apology to the real artists and your readers. It was the worst of taste. You should consult a doctor about this. It is not art.”

Koplos’ run ended with the February/March 2010 issue, and deputy editor Shannon Sharpe took over for four issues. A strain of social consciousness runs through those issues, perhaps foreshadowing later coverage of craft artists such as Aurelie Tu and Michael Strand. June/July featured a piece on prison inmates finding meaning and redemption in quilting; August/September, a priest who works as a sustainable-fashion designer. Only four letters appeared in Sharpe’s issues.

THE MOSES YEARS

2010 – PRESENT

In 2010, the ACC moved to Minneapolis; no New York staff chose to come along. So the magazine began again, with mostly new staff. Senior editor Julie K. Hanus and I, with longtime contributing editor Joyce Lovelace, creative directors Mary K. Baumann and Will Hopkins, and copy editor Judy Arginteanu, took up the path.

We’ve taken our share of criticism in letters – these days, they mostly come as tweets and Facebook posts, with the occasional blistering email. In a few cases, I think the interchange has contributed to the ongoing, incremental debate about how closely craft should consort with art. In April/May 2014, I interviewed Tim Tate, co-founder of the Facebook forum Glass Secessionism, which basically holds that it’s time to move past the studio glass world’s love affair with technique. Some readers admired Tate’s insights. Others felt that, once again, craftspeople were taking a stand without being as well informed, historically and theoretically, as they should be. Lani McGregor of Bullseye Glass Co. emailed to say she agreed with glass scholar and curator Tina Oldknow, “who recently described glass secessionism as ‘little more than coffeehouse chatter . . . unless there will be some academic rigor behind it.’ We all enjoy our coffee and our chatter. Revisionist history, not so much.”

In the next issue, we published Bruce Metcalf’s essay, “Hot Glue & Staples,” which argued that craftsmanship should not be so reviled in contemporary art. Who could disagree? Well, Jason L. Starin did. He tweeted, “I read this story a few hours ago, and it’s still irritating me to no end. What year is this? 1914?” (That’s the problem with Twitter; brevity’s great, but what, exactly, was his beef? I miss the old-school paragraphs of the ’80s.)

Earlier this year, we interviewed the editors of Sloppy Craft. Coverage doesn’t mean we endorse someone’s ideas, of course; it means we’re curious about them. But a lot of readers didn’t see it that way. “American Craft Council, you need to raise your standards instead of lowering them,” Cindy Billingsley posted on Facebook. “Let’s get off this bandwagon in craft and art of rewarding no skills [and] sloppy work. No wonder the general public has no idea what good craft or art is.”

Hold on – did you see how she combined “craft” and “art” in the same sentence? Twice. And casually, probably without really thinking about it. Like a lot of people today, she apparently sees no conflict between the two. Nuanced differences, maybe, but not loaded conflict.

Today the magazine tends to focus on the good that artists do in the world and on the universality of the creative impulse. We try to speak to a broad creative audience, and we feel some urgency about making craft relevant to people who may not know its legacy. Why? Fewer people make things today – and we think making things is good for the soul, and by extension, for the world. We’re not above trying to inspire people to find their own creative spark, in whatever way is meaningful to them, however naïve that might sound.

The other day, I was at an opening at a museum, chatting with an art critic, who, I detected, doesn’t really like today’s American Craft. “You don’t pay much attention to the differences between art and craft,” he charged.

“Yeah,” I said, “we’re not really so interested in that. We’re mostly fascinated by the fact that, since the dawn of time, human beings have felt compelled to make things.”

“Well,” he sniped, “most of what they make isn’t very good.”

So after six years as editor of a 75-year-old magazine, I say to the craft world: Go ahead, emulate the art world. But not like that. Not like that!

Special thanks to ACC librarian Jessica Shaykett, who contributed reporting to this story. Megan Guerber, Molly Geisinger, Joyce Lovelace, Dulcey Heller, and Beverly Sanders (senior editor, 1980 – 2010) also contributed.