Russel Wright: At Home with Nature

Russel Wright: At Home with Nature

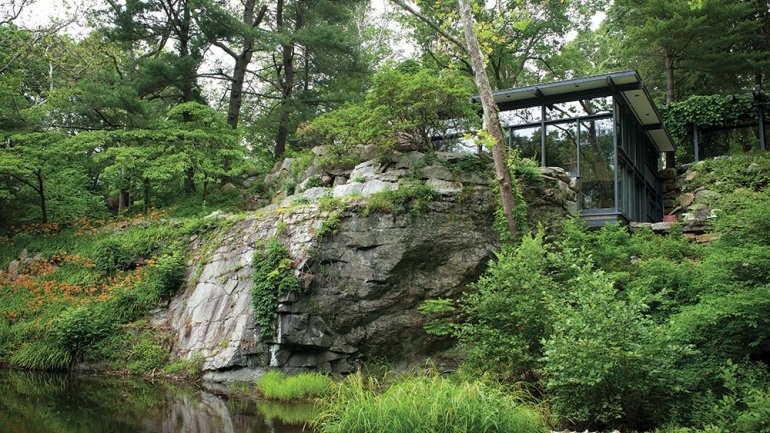

“Russel Wright: The Nature of Design” explores the industrial designer’s relationship with the natural world. The exhibition, which originated at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz, documents Wright’s most personal project: the building of Manitoga, his weekend estate in Garrison, New York.

Curators Donald Albrecht and Dianne Pierce sat down with American Craft to discuss Wright’s goal of bringing to American culture “an intimacy with nature,” how he achieved this at Manitoga, and how it resonated in his work.

In 1942 Wright purchased land in Garrison, but it wasn’t until the late 1950s that he started to build Manitoga. Why did it take him so long?

Dianne Pierce: Wright wanted to find a place where he could successfully marry architecture and landscape, so he made a point of getting the land first and understanding and studying each inch of the site. He looked at many, many different sites before choosing this one. He spent many moonlit nights sitting and looking at the way the light fell on the site. It was always the land before [the] architecture for him.

Donald Albrecht: The failure of the American-Way project – Wright’s attempt in the late 1930s to partner with craftspeople, manufacturers, and retailers to offer home goods, craft, and mass-produced items to the masses – spurred Wright and his wife, Mary, to find a retreat from New York City.

They would go on the weekends, and he would study different views. Along the way, Wright hired an architect named David Leavitt, who had done some projects in New York in the Japanese style, an aesthetic Wright liked.

The exhibition opens with Wright’s 1959 Ming Lace Flair dinnerware, which has real leaves embedded in translucent melamine, very different from the 1939 American Modern dinnerware that made Wright a household name. Tell me about your decision to start with this series.

Albrecht: Ming Lace is a great example from the period because, like Manitoga, it combines the man-made and the natural. Like Wright’s butterfly screen, which has butterflies embedded in plastic, this yin and yang is the story of Manitoga.

Pierce: That is what we really wanted to focus on, his interest in combining the yin and the yang, the man-made and the natural, the hand and the machine.

What are some of the experimental design elements in the buildings of Manitoga and their surroundings? In the exhibition you say Wright blurred the boundaries between inside and out.

Pierce: There is almost nothing about it that is not experimental, really. Even though he worked with an architect, he ignored most of his advice and really did his own thing – to the detriment of the engineering.

Albrecht: He blasted the kitchen out of rock, and now that area is constantly flooded. He embedded natural materials – the pine needles in the green plaster walls, the butterflies in the screen, the boulders as stairs, the tree in the living room. It fits in with his DIY approach; you can make your own screen.

Pierce: His roof (on both the studio and the house) was a very early American example of a green, or living, roof. He didn’t necessarily expect the vegetation on the roof to grow, but it did, and apparently Wright left it because he liked the look of it.

I haven’t thought of Wright as an ecological designer. Is that how you would describe him?

Albrecht: Yes. What is interesting about Manitoga is how he claims, then reclaims, and then expresses the former human activity at the site. At the entrance of the house, there is a big rock with a metal hook that was used for logging the quarry, which he has left, so he doesn’t erase the past. He is not Rousseau; he doesn’t say, “I am returning this to its natural Garden of Eden state.” He lets you know that there has been evidence of people working at the site by stone quarrying or logging, and he celebrates that. I don’t know of anyone who did that before Russel Wright. Now it’s kind of common, but not then – he really leaves evidence of former activity that

is not idyllic.

The design of Manitoga is an exercise in controlling nature. Where did he get the inspiration, the vision, for this home?

Pierce: It is very much a manipulated landscape. Whether Wright was overtly inspired by anyone who came before is hard to say. But what he did differently at Manitoga was to create “wildness zones” radiating out from the most cultivated areas near the house to the most undisturbed at the edges of the property, a sort of concentric ring of progressively manipulated landscape. Just one of the paradoxes of Wright is that he wished his landscape to look as if it happened that way naturally, but he was acutely conscious of his own role in creating it. Wright transplanted foliage to create swaths of a particular type of fern and an enclosing wall of mountain laurel to create a room in the landscape. He also rearranged stones, including very large ones, which he picked up using an old truck with a winch and then rolled down the hillside until the effect was pleasing. He planted a vine over a pergola to create a sort of curtain, separating the entry approach from the view of the quarry pond. He rerouted a small brook to run into a quarry so that he could have a waterfall.

Albrecht: Wright liked seasonal changes; the house had a fall look and a summer look. He knew exactly what dinnerware should be used and what foods would look good on the dinnerware. And there were menu books. It was all very, very carefully orchestrated.

“Russel Wright: The Nature of Design” will be on view at the New York State Museum in Albany from May 4 through December 31.

Bella Neyman is a design historian based in Brooklyn. She blogs at objectsnotpaintings.com.