To See Clearly

To See Clearly

On a warm spring day in Los Angeles, glass sculptor Jaime Guerrero is in his studio, contemplating a work in progress. He’s quietly excited, because in scale, concept, and emotional reach, it’s shaping up to be one of the most ambitious of his career to date.

It’s an installation that ultimately will fill a small room. Guerrero’s vision is this: Life-size children made of clear glass gather around a hanging glass piñata. A little girl covers her face with her hands, hiding or maybe crying. Over by a fence, a brother and sister, both blindfolded, grope to find each other’s hands. A fourth child, also blindfolded, holds a big stick, ready to swing at the piñata and break through to the delights it contains.

It’s a happy, playful scene – a party. Or is it?

For Guerrero, the ghostly figures – faceless, anonymous, almost invisible – represent the thousands of undocumented children crossing borders to escape poverty, persecution, and war, uncertain of the journey and the future that awaits them. With this work, he aims to highlight the human dimension of a critical issue of our time: immigration and the plight of refugees.

“Living in Los Angeles, and in a predominantly Latino neighborhood, it’s something that’s real and evident all around us,” says Guerrero, an American of Mexican descent. “But it’s also reflective of a larger humanitarian crisis happening in the world. I’m trying to bring attention to the issue, in the hope that people will open their minds and hearts. These are innocent kids, who have nothing to do with politics. They just know they have to leave their home.”

One of only a few sculptors creating large-scale figures in blown glass, Guerrero makes heartfelt, expressive works about identity and humanity. A handsome man of 43 who looks a bit like actor Andy Garcia, he wears dark, opaque lenses in his prescription eyeglasses – an odd choice for an artist who says he is interested in the transparency of glass. Yet even when you can’t see his eyes, his engaging sincerity comes through, the same spirit that suffuses his art. Almost every piece is blown, sculpted, and assembled hot, as he works in immediate, intuitive fashion to create form, gesture, and detail.

For all their intensity, there’s a subtle, illusory quality to Guerrero’s characters. The same haunted air of the piñata children is present in Ni Aquí, Ni Allá (“Neither Here nor There”), a life-size figure of a man with his head down and hands up, dressed in worn jeans and a T-shirt bearing the logo of the United Farm Workers. “He has a certain look that to me is familiar, of a person who’s broken – brokenhearted or defeated,” Guerrero says. “Maybe his story is that he migrated to this country to work long hours in the heat, and now he’s being criminalized.”

The theme of arrest recurs in Encarcelados (“Imprisoned”), a series of glass arms protruding from a wall, capturing “the moment police tell you to put your hands behind your back.” Painted with lush tattoos, the arms are submissive in attitude, yet cast bold, emphatic shadows – an alternate reality. It’s one of the powerful effects of glass that Guerrero can’t always predict, that happen almost magically, he says, once “you respect the process, step back, and let it happen, let it reveal itself.”

A sense of the value of craftsmanship runs deep in him. “I come from a culture where what you make with your hands is important. In some ways, it defines who you are.” His father was head chef at a big Mexican restaurant in downtown LA and invented his own cuisine, Guerrero says. “He had a particular way of making chile verde, and there was a dish named after him. My mom also was an extraordinary cook, the queen of salsas.” A family tradition was the Mexican charreada, a competitive event similar to a rodeo involving horses, cattle, riding, and roping, with flowers awarded to recognize skill. Guerrero remembers a childhood trip to Zacatecas, where an uncle was a champion charro. “His horse was 10 times more adorned with flowers than anybody else’s. For me, as a kid, that was huge. I had a hero.”

As a student at California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, Guerrero fell in love with glassblowing at first sight: “I realized that was what I was going to be focusing on for a very long time.” While art school gave him the basics of the craft, he learned the most from Italian master Pino Signoretto (“one of the best sculptors who ever lived”), watching him in action, first at the college and later in Italy and at Pilchuck Glass School in Washington. After graduating in 1997, Guerrero supported himself producing colorful, decorative vessels sold in galleries and at Gump’s in San Francisco. His ultimate goal, though, was to take glassmaking into the realm of sculpture – to comment directly on pop culture, Mexican street art, “things related to my experience growing up in East LA.”

Early on he made a body of work called Homies, small figures based on people he remembered from his neighborhood – “a guy in a Mexican restaurant, people hanging out on the corner drinking a 40. It was a very specific look, those traits or idiosyncrasies or characteristics that I was translating into glass form,” Guerrero says. “I was interested in creating not just a stiff figure that represented Latino culture, but going further into the essence of personality, through posture.”

From there, he continued to explore concepts of identity, old and new, in glass. He made masks inspired by those worn in lucha libre, the Mexican version of pro wrestling. Recalling when uncles and cousins took him hunting at age 12, he did a series of animal trophy heads that question the notion of a time-honored yet violent rite of passage. And for a while now, he’s been creating Mesoamericans, his series of modern interpretations of pre-Columbian artifacts. It’s a way, he explains, of “understanding these objects through making them; understanding my ancestry, where I came from. There is a drive for me to make these. I haven’t fully encapsulated why. But there is a reason.”

Just as compelling for Guerrero is his passion to give back. His base is a former warehouse he leases in LA’s Boyle Heights neighborhood, not far from his childhood home. The building has several studios he subleases to other artists (“it’s important for me to create community”), along with a few rooms for himself. There’s a small facility for glassblowing, but he doesn’t make much of his work there; for his big pieces, he has to borrow outside studios equipped with oversized furnaces. Instead, this hot shop is set up for one main purpose: to offer free glassblowing classes to teenagers in underserved communities.

“I was lucky enough to not get into trouble growing up,” he says. “But there are extremely talented kids out there who fall through the cracks. They may go to jail, get shot, find themselves in a trap. It takes a little effort to expose them to something new, different, and exciting. And that’s what glass is, for them and for me.”

Guerrero used to run a modest glass studio at the Watts Labor Community Action Committee, a social services organization in South Central LA. “I can comfortably say in the four years I was there, I taught about 500 kids how to blow glass.” Those classes ended when funding ran out in 2015, so he launched a Kickstarter campaign to start his own program. “I see a huge transformation that happens with some of these kids,” he says of his students, who learn creativity, teamwork, and in some cases, a trade. For communities struggling to get basic resources, an expensive medium like glass is definitely a luxury, Guerrero points out. “But it doesn’t have to be, if more artists find a deeper responsibility to give back and help those in need. These kids will jump in wholeheartedly and embrace what you have to offer.”

Happily, it’s an idea he sees starting to spread, as new initiatives spring up “that acknowledge the need for diversity in the glass community.” Two of his students, for example, have participated in a new program at New York’s Corning Museum of Glass that gives talented high schoolers an immersive week of exposure to its world-class facilities and collections.

Between art, teaching, and family – he and his wife, Jenny, have a toddler daughter – it’s a busy life these days, and he’s grateful. He feels he’s hitting his stride, after a long and dedicated effort to get “good enough” technically to express himself in the demanding medium of glass. “It’s taken 20 years, but now I’m at a place where I can make a statement and have an impact. I’m hoping somebody listens.”

Guerrero’s installation Broken Dreams debuts in the exhibition “Mano-Made: New Expression in Craft by Latino Artists” at the Craft in America Center in Los Angeles (August 26 – October 7). This fall he’ll be featured in “Borders and Neighbors,” the latest episode of the Craft in America PBS series. “Contemporary Relics: A Tribute to the Makers,” a show of new Mesoamerican works, is at Skidmore Contemporary Art, Santa Monica (September 16 – October 28).

‘I Found It’

A former student discovers his own path.

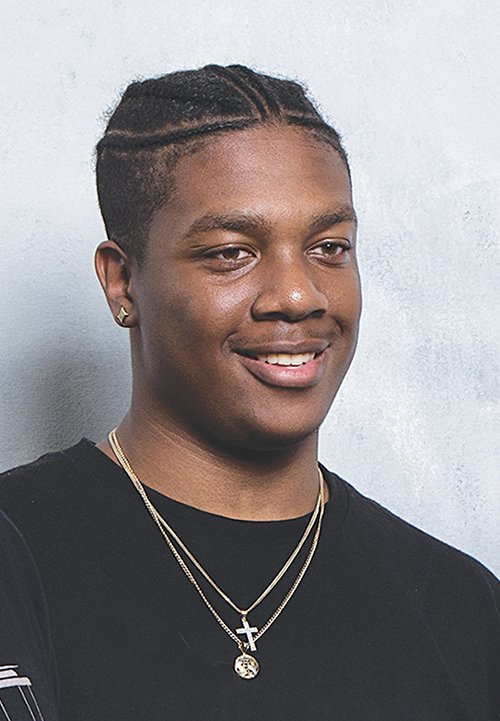

Tyler Straight was in middle school when he started learning from Jaime Guerrero how to blow glass. Now 19, the soft-spoken young man has lately been the main assistant to Guerrero, whom he regards as a mentor and big brother. A native of Watts, he’s a little tired of the terms “at-risk” and “underserved,” but recognizes the rare opportunity glassblowing offers to kids like him. “I guess we’re just kind of – we’re missed. Can I say that, ‘missed’? It’s like, I’m not even supposed to be doing this. And somehow I found it.”

He’s been on an artistic path ever since and wants to eventually combine glass with mixed media. “I lean toward luxury, chandeliers and stuff. Things that pop at you, grab you right away,” he says. He’s still focused on “simple things like vases and cups. I’m trying to get them really clean before I move into sculpture, just get down to basics first. That’s really important.”

Straight was the second of Guerrero’s students to go to New York for the Corning Museum’s young artist program, aptly named Expanding Horizons. He dreams of more glass-related travel: “Italy is the No. 1 place they keep telling me to go – Italy and Pilchuck.” For now, he’s continuing his glass studies at Santa Monica College. He’s also been hired to run the newly reopened community glass studio in Watts, where he first took classes with Guerrero. “I want to continue that cycle, go back, teach other kids how to do it, just keep going,” he says.

“Glass takes a lot of time, patience, and dedication. That’s very needed where I come from,” Straight reflects. “You know, something to spend our time on, instead of being on the streets or doing something bad. We just put it into our art form. And each kid has their own story, or a way of visually saying things. So you never know. Something great – the next Lino or something – might come out,” he says with a smile, referring to the world-renowned glassblower Lino Tagliapietra. “You never know. I’m just saying.”