The Sky Is No Limit

The Sky Is No Limit

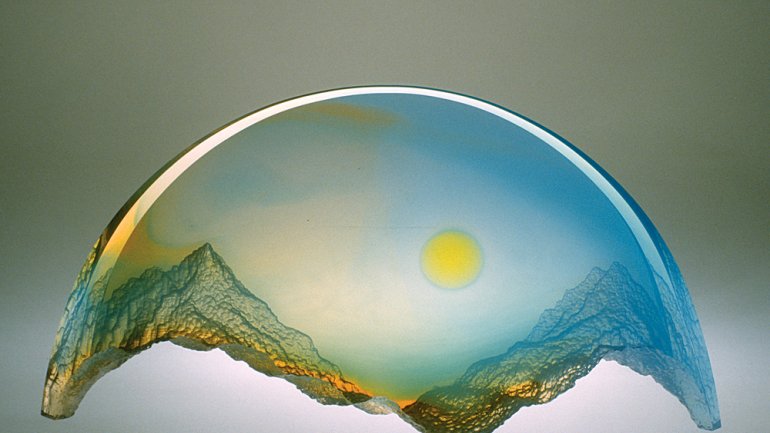

Glass artist Mark Peiser's career is defined by innovation.

“The key-note, the standard of scale, and the chief organ of sentiment.” That’s how landscape painter John Constable described the sky nearly 200 years ago – a description, Mark Peiser says, that still resonates today. For more than 40 years, Peiser has experimented with equipment, materials, and processes in a quest to capture in glass the transparency and luminosity of the sky. For the contemplative artist, this lifelong exploration also raises philosophical questions.

“If you think about it, the form of a sculpture of the sky presents some problems. Like, have you ever seen one? Like, where are the edges?”

Challenges of interpretation and representation only fuel Peiser, who works in blown, kiln-cast, and hot-cast glass. “My pieces all begin with a feeling in my gut. Then I think about it, identify it, visualize it, make sketches and models. Sometimes all that comes together into what I think would be a worthwhile piece. Sometimes that takes over a year. Sometimes never.”

In the case of opal glass, a technically enigmatic material, the artist has wrestled inveterately with the visual possibilities. (The glass refracts light in unpredictable ways, so anticipating the perceived color of an object once it comes out of the annealer is a gamble.)

Peiser began his Palomar series in 2007, inspired by the creation in 1948 of what was then the world’s largest optical telescope. For four years the artist tackled modern-day iterations of the technical boundaries his predecessors experienced six decades prior. As Peiser advanced his tests and formulas, he was pleasantly surprised to find that in spite of opalized glass’ inscrutable nature, several “failed” works conveyed great beauty. (“I approach just about everything as an experiment. Frequently I have no idea what to expect. Sometimes I get lucky,” the artist notes.) One such piece, Section One, Veils, was quickly acquired by the Corning Museum of Glass for its permanent collection.

Peiser’s inquisitiveness goes back to a childhood spent devouring Popular Mechanics magazines, mastering the construction potential of Erector sets, and exploring the great outdoors around his family’s Chicago-area home. His analytical nature propelled him through successful early careers in industrial design and model making, which he boldly abandoned in 1965 to enroll at DePaul University and pursue his dream of studying music.

After two years, however, Peiser realized he wasn’t cut out for life as a full-time pianist. Knowing he loved hands-on work, he headed in 1967 to North Carolina’s burgeoning Penland School of Crafts for a five-week class in glass. There, he quickly acquainted himself with the basic tools and limited written resources available at the time. “I was told there was no information available beyond what I saw,” he says.

“I found the only way to learn was through experimentation in all aspects of studio existence.”

And experiment he did. Peiser was made Penland’s first resident glass craftsman, a post he held until 1970, when he established his own studio nearby. “Most of my career has been spent evolving glasses and processes,” Peiser says. “Like many of us in the ’60s, I strove to be an advocate for the material and new approaches to its objects.”

For Peiser, elected to the American Craft Council College of Fellows in 1988, curiosity has no limit. Recently he referenced his musical past for his Etude Tableau series, the title a nod to composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. These works, along with his concurrent Passages series, consider how the sky transmits a hue through refraction. In Peiser’s work, different thicknesses of glass convey the varying hues and volumes of colored light, creating visual presence in the material.

“In my head I think of this material as imbuing the space of glass with atmosphere, not emptiness,” Peiser says. “If it were music, it perhaps establishes a key signature for the piece. Somehow these glasses and how they deal with light resonate within me, and I yearn for them to be part of my vocabulary.”

Jessica Shaykett is the American Craft Council librarian.