Think Globally, Dress Locally

Think Globally, Dress Locally

We’re all familiar with the local food movement – it’s considered eco-friendly (not to mention trendy) to know where your dinner comes from. But what about the clothes on your back?

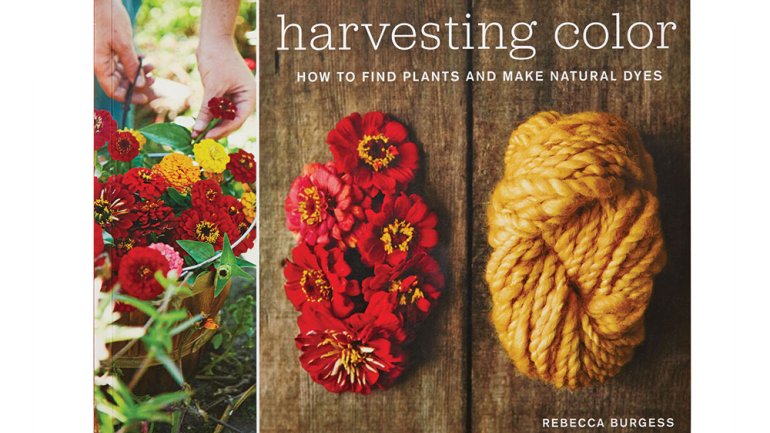

Rebecca Burgess, a Bay Area textile artist, wants clothing to occupy a similar place in the public mind. In 2010, via Kickstarter, Burgess funded the creation of a “bioregional” wardrobe, vowing to wear only clothes made from natural fibers and dyes sourced within 150 miles of her home – for a whole year.

The project posed huge challenges. Eating locally is easier than it used to be, with the advent of farmers’ markets and community-supported agriculture. There’s no such infrastructure for textiles. Burgess sought out cotton farmers, alpaca and sheep ranchers, mills, designers, knitters, and weavers to build her wardrobe; in the process, she recognized a glaring need to develop local connections, expertise, and systems.

As her one-year challenge drew to a close, Burgess founded Fibershed, a nonprofit that establishes local textile networks, strengthens regional supply chains, and does outreach and education. (The name echoes the notion of a watershed, a geographical region defined by the main body of water that smaller lakes, streams, and rivers contribute to.) And the idea caught on: The pilot Northern California Fibershed has already spawned more than a dozen other programs in the United States, England, and Canada.

Looking back, what inspired the one-year challenge?

I was teaching textiles to children and adults – and I realized I was teaching things that I wasn’t really living out myself. I was weaving, but I wasn’t wearing what I was weaving. I was naturally dyeing things, but I wasn’t wearing things that were naturally dyed.

So the intent was for me, personally, to start doing something different with the way I dressed myself. How to walk the talk, interwoven with concerns about climate change, fossil fuels, polluted water, the effect of effluents … all of that tied in. Could I offset – and unplug – my relationship with these unhealthy systems?

We’re living in an era of regional economic development, too. So dressing myself locally with homegrown dyes, regionally produced fiber – if you look at all of these currents coming together, they form an interesting moment. As I shared my trials and tribulations, and the stories of the people I was meeting, the movement started building on its own.

What was the biggest challenge to dressing locally?

If you’re a naked human being and you want to dress yourself, what would you put on your skin? It’s not as simple as food; it’s not putting something in your mouth and chewing it. You have to process the materials, weave them, and more.

The greatest challenges were actually around the creation of cloth. There were only a few local people who even had the skill to produce anything on the loom to begin with, and the raw materials we were providing them were very chunky. We did have two archived fabrics that were made in the area before NAFTA and the free-trade agreement took effect. So there was an opportunity for some people to do some sewing.

I found that the best sewers were not necessarily the people who call themselves designers. I was taken aback by young fashion and textile grads. Everyone can draw well, and they’re good at visualizing a design. And yet they want someone else to make the pattern. They have a love of textiles, but they have no idea how to create a textile or form a textile around a human body.

So you found a lot of people who were eager to design, but lacked the material knowledge to execute those designs.

Pretty much. What I think we’re preparing them for – well, I don’t know if we’re preparing them well – is working in an industry where designs are done in this country, and then sewing is done in another country. I think we’re leaving people really high and dry, not giving them a more full-bodied education.

I would get partially made garments, or garments that didn’t fit well, or accessories; everyone wanted to make a scarf. I started to appreciate what is required to make a three-dimensional item that goes over the body. I don’t take that for granted. I cherish sleeves and pants that fit well – they aren’t easy to come by.

Obviously, a move toward local clothing would require a fundamental shift away from a “design here, sew there” system, away from fast fashion.

My natural dye classes start with an hour-long presentation about the externalized costs of ecology and labor. The face-value cost to shop at Walmart versus the real cost of shopping at Walmart: the Pearl River Delta [an industrial region in China], where most jeans are made [and the resulting pollution]; genetically modified cotton fields; suicides related to that kind of practice because farmers are so deeply in debt – all of that is in my presentations. And now we’ve got the Bangladeshi labor crisis; if that is not a wake-up call to fast-fashion consumers …

We can educate our way out of some of those consumptive patterns, but the tricky nugget is: How do we dress the single mom with two kids who shops at Walmart because that’s all she can afford?

We’ve dug an economic hole for so many people where they can’t really get out of fast food or fast fashion. People earning low wages can afford only cheap goods; meanwhile, companies keep wages low so they can sell those “affordable” products. There’s a growing number of impoverished people in this country – how do we get away from purchasing things that create a cycle of even more poverty?

I think you can grow clothes and you can grow food. But we have to get back to some basics in some of these communities that just have a Burger King and a Walmart. We can’t just bring in a high-end shop and expect people to go there.

What role can education play?

Institutionalize it in the public school system. There are examples, like the Waldorf school tradition, where children are learning to knit from first grade on. It would be really inspiring to see communities start evaluating what children really need, which are the skills to get through a really tricky time on Earth: how to grow food, mend clothes, etc. I’ve been working with schools that can afford Fibershed workshops, which is a problem because they’re only going to a certain class of students. But this year we’re developing a felting curriculum, and will give workshops at underserved schools in the East Bay next year.

We’ll be teaching children about animal husbandry, as well as fiber technology – how to wash it, card it, felt it, and how to make a garment from their own material; and it’s all connected to state educational standards.

One Fibershed initiative is its online marketplace to connect farmers, artisans, and consumers. How do you partner with the craft community?

In that first year, it started with me fishing for them. Now they tend to find us. Artisans spread the word. It’s really an interesting network. Again, at first, I found a lot of designers; we have a lot of people who draw, but not a lot of people who construct, and not many people who construct well. I think that’s a fault of the education system. People aren’t being trained to use their hands.

Fibershed incorporates education and activism, but you also focus on scalability and infrastructure. Building textile mills to facilitate local, sustainable processing of fibers is among your long-term goals.

The producers – farmers, ranchers – are like, please do something; we want to be able to process our materials! But you have to be careful; if you’re not making a yarn that can be finely woven or knit, you just have a big batch of hand-knitting yarn. You can only sell so much of that, and you can only teach so many people to knit, and most people are not going to knit their own clothes.

So my commitment is to appreciating and respecting the whole spectrum of production, from people who are raising their own animals and hand-spinning all on their own farms to companies like Ibex that are interested in using a domestic wool supply chain to make yoga pants. And if you’re looking at using local fibers and creating a solid regional economic plan, there’s a level of scale and commercialization that you have to do. Most people aren’t going to pay $600 for a handspun, handknit sweater.

That’s why Fibershed encompasses all those processes. Even the person buying the yoga pants – to me, every human being – should know what it takes to handknit something; to weave; to dye using plants; the true costs of color, the true costs of fiber, and the true costs of production.

That’s what I think every child needs to grow up with. Then if you grow up and you want to be a farmer or an engineer, at least you know.

Danielle Maestretti is a frequent contributor to American Craft.