What You See Is What You Get

What You See Is What You Get

“Part of the reason I’ve taken up fiber work,” says Liz Whitney Quisgard, “is that I really don’t want to be associated with today’s breakdown of painting.”

The 88-year-old, surrounded by piles of yarn in her apartment in New York’s Little Italy, is flipping through a contemporary art magazine, reviewing its contents with the eye she deployed as an art critic for the Baltimore Sun in the late 1960s (before she got fired for being “kinda mean”). She scoffs every few pages, peppering her conversation with critiques:

"Rothko was interesting in his time because nobody else was doing [it]. But why do practically the same damn thing now?”

“There are so many artists who are still doing action painting and getting credit for it. That’s like beating a dead horse.”

“I have no patience for total minimalism. You’ve seen one white canvas, you’ve seen them all.”

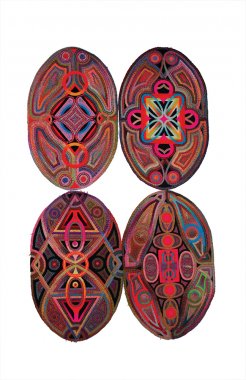

There are other, more practical factors that led Quisgard away from painting, her primary medium for more than 50 years. Even with a large basement studio, it’s cumbersome to store and transport large canvases, and as she approaches her ninth decade, fiber is a more accommodating medium. But as motivations go, her appraisal of the state of modern painting should not be ignored. Shaping her legacy is as important to Quisgard now as at any other point in her career. In the 15 years since she began producing yarn-on-buckram work, her signature aesthetic has remained the same, with traces of Byzantine architecture and ancient Arabic patterning and iconography.

Also enduring are her goals: “world fame,” yes, but also the greater legitimization of ornamental art. “My work is totally decorative. It has no meaning beyond ‘What you see is what you get,’ ” she explains. “And I’d like people to say that I made the term ‘decorative’ not only respectable but admired.”

It’s no surprise that an artist so uninterested in the meaning of her work could switch mediums with little sentimentality. “At first, my fiber work was a casual experiment, not to be taken seriously,” she recalls. “I was doing long, narrow wall hangings. Then several were included in my show at the Frist Museum in Nashville in 2003 and were purchased by Vanderbilt University. I figured, ‘If they’re taking them seriously, maybe I should, too.’ ”

She switched to fiber full time a few years later, putting an indefinite pause on a painting career that began in the early 1940s. Quisgard was born in Philadelphia in 1929 but moved with her family to Baltimore as a child. A self-described “dedicated bohemian,” she took to the arts at a young age. “I’ve been a lifelong painter,” she says. “I did my first portrait commission at the age of 14 and my first mural commission at age 16.” She studied painting at the Maryland Institute College of Art and after graduation anticipated a life as a fine artist. A degree of success arrived in the early 1960s, when her large-scale “bold geometric” paintings earned representation in the Emmerich gallery in New York. The relationship was fruitful, but when it dissolved six years later, Quisgard found herself still in Baltimore, a mother of two teaching at assorted institutions for a living, grappling with trends in art that were diverging from her own interests, and simmering with frustration that she hadn’t established herself in New York. (She made the move in 1981, after a family inheritance provided the wherewithal to do so.)

What emerged from the ensuing period was a deeper commitment to her philosophy of decorative art and the development of a style that continues to define her approach. “The strongest, most lasting influence on my work has been Islamic rugs,” she explains, recalling how she’d indulged in pricey antique Oriental rugs in her 30s. “I don’t copy them. I simply absorb them to such an extent that the idiom comes out in the work.” Her aesthetic was further shaped by a passion for architecture.

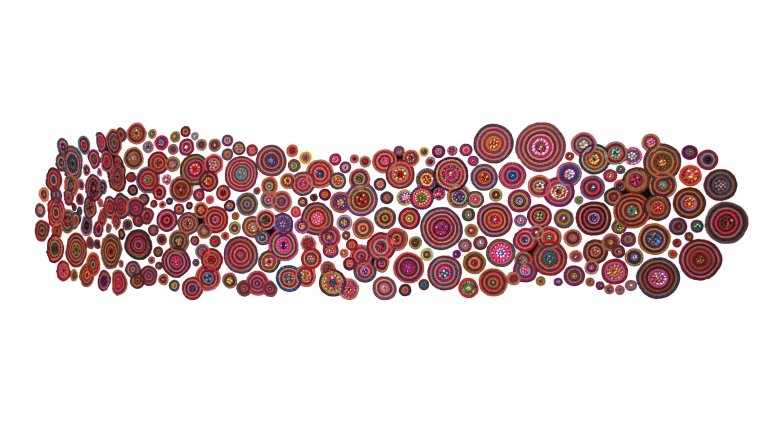

Quisgard’s fiber work makes manifest those varied influences. Her current displays are vast arrangements of small to medium pieces affixed to stretches of wall: Scramble (2017) features amoeba-like shapes nestled against and within each other, while Hundreds of Circles (2017) is … well, you can imagine. The assemblages were displayed at Kingsborough Art Museum in Brooklyn last year, concurrently with another show at the Quick Center for the Arts upstate (running through June 30). Though they form a whole, they retain some of Quisgard’s own stubborn independence; they’re like “an enormous picture puzzle that refuses to fit together,” she says.

What Quisgard says fiber offers that painting couldn’t, beyond an opportunity to extend her career, is a kind of freedom. She can create outside the restrictions of a rectangular frame and still retain the essential DNA of her work. “While her paintings and sculpture are intricately embellished and visually stimulating, her fiber work is even more remarkable,” says Les Christensen, director of the Bradbury Art Museum at Arkansas State University, where Quisgard exhibited in 2016. “She achieves extraordinary results with just manufactured yarn and buckram.”

The trade-off for Quisgard is that fiber work takes considerably longer to produce – she estimates that it takes her about 50 hours for an average 2-by-2-foot Scramble piece. “I’m a fast painter but a slow knitter,” she jokes, but she’s confident she’s in the right place at this stage in her career and legacy-building, as a non-representational fiber artist whose work still bears the fingerprints of a lifelong painter. “I’m noticing, among the action-painting crap and minimalist garbage, the occasional what I would call ‘decorative imagery’ emerging,” she says. “I just hope it doesn’t emerge too fast, because I want to get my share of the credit for it.”