When Beauty Is Suspect

When Beauty Is Suspect

I was once hired to design a publication about one of the most commercially successful architects in the United States. As I did my research, I became enthralled by the man’s work - a museum that looked as if it were growing out of a hillside, a light-infused airport that seemed to hover in the clouds, a government center standing in a desert like a minimalist, modern castle. I was in the presence of greatness.

Then, as I dug deeper, the story grew more complex. He’s not all he’s cracked up to be, some in the field whispered. It’s not that he’s a great architect, they said; he’s a great marketer. He’s using tricks to draw the eye. His work isn’t original.

I wasn’t any less captivated by the guy’s work after I heard those things (and I did wonder about professional jealousy), but they gave me pause.

I thought about this as we put together this issue focused on glass. This year marks the 50th anniversary of studio glass in the United States, and the story of the rise of glass in this country is a fascinating one.

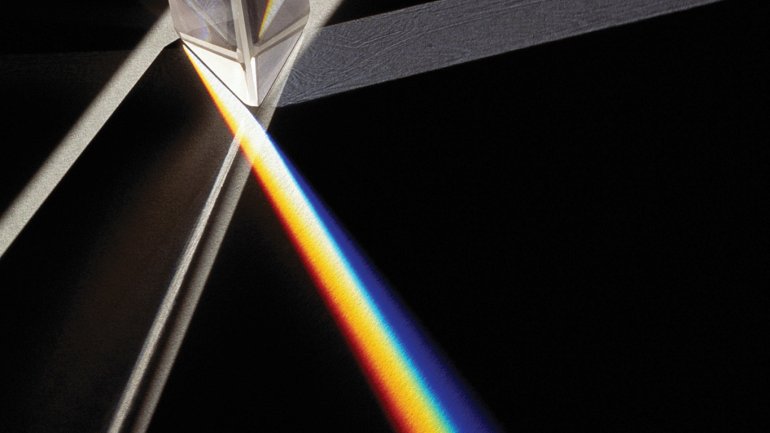

Glass stands apart from other mediums in significant ways. For one thing, as an art material, it’s young. Because it requires a specialized furnace, hot glass has been in the gloved hands of individual artists for only five decades. And glass may be more obviously dazzling than other mediums. Douse it with light and color, and the result is otherworldly. You want something amazing in your atrium? Go with glass.

Glass also came of age at a time of rising expectations in the field of fine craft, a time Beverly Sanders alludes to in her review of the “Crafting Modernism” show. Artists were gaining mastery over glass as modernism was shifting to post-modernism, when the reigning ethic moved from “surround yourself with objects of beauty and wonder” to “demand meaning of those objects of beauty and wonder.”

In its formative years, as American glass was ready to strut its stuff, the more sophisticated voices in the craft field wanted more. Beauty is fine, they suggested, but not at the expense of a brain.

You can sense the skepticism about glass among critics such as Glenn Adamson. He is wary of the “beauty contest” among glass artists and cautions them against capitalizing on the medium’s “easy pleasures.” The glass work he favors is less colorful, less dazzling, more cerebral in its impact.

That’s the role of criticism, of course, to push artists, and art lovers, beyond what they think is possible. And the more you know about an art form, whether architecture or fine craft, the more skeptical you tend to become of its seductive qualities.

But I recall how affected I was by the work of a leading architect, before I knew very much. I was moved – and what is art for, if not to captivate us?

The left brain parses and deconstructs, sometimes very impressively. But the right brain feels and wonders, and that instinctive, emotional response matters too.

I want it both ways: not duped by the shiny object but not impervious to sheer beauty either. Can we have it all?