Who Needs Education?

Who Needs Education?

Every artist does, whether it's formal or not.

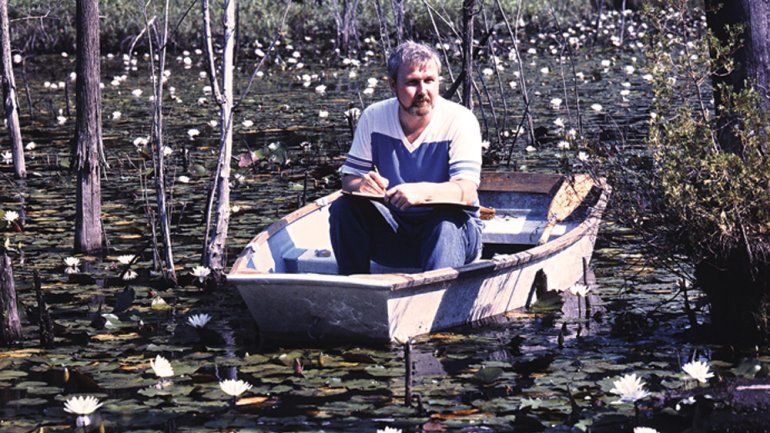

Paul J. Stankard is a fellow of the American Craft Council, the author of two books, a devoted teacher, and an internationally recognized glass artist with work in more than 50 museums worldwide. He achieved all of this despite never having studied art at the university level; he trained in a vocational glass program and determined much of his own subsequent education.

Stankard has a special interest in education for artists – especially those relying on their own resources. We asked him to suggest tools for artists eager to grow, with or without formal degrees.

For your students at Salem Community College, you made a list of 100 glass artists respected by the glass community and you discovered, after researching their backgrounds, that almost all of them had BFA or MFA degrees. What does that say about the difficulty of rising to the top for a self-taught artist?

Whether one is self-taught or a graduate of a formal arts program, rising to the top of your field and being recognized for doing significant work is difficult. It’s a major accomplishment. Very few reach this level. Formal education isn’t required to reach upper-echelon status as an artist or craftsperson; however, artistic maturity is.

When I first discovered that most of the artists on the list I developed for my students had formal art degrees, I viewed it as a teachable moment. My students and I discussed the potential advantages of studying art in a university setting. From my perspective, as someone who did not attend art school, the advantage is that university students, from day one, are exposed to excellent work from the past, encouraged to develop concepts for discussion and critique, and asked to approach the material and concepts from the perspective of self-expression. Perhaps the most important asset is having their work critiqued within a creative community.

This background prepares BFA and MFA students to embrace the contemporary American craft movement – to bring fine-art expectations to object-making. Makers like me, who came to artmaking from a vocational background, have a foundation in hand skills and technique. Early in my career, when I met artists and craftspeople with an art school background, I was impressed with their art vocabulary and knowledge of art history, and sensed they had more creative freedom as a result.

Ultimately, though, the art world’s expectations for significant work are the same, whether an artist is academy-trained or self-taught. And to do significant work, you need to combine an impulse to be creative with an education directed at your passions and interests, however you obtain it.

How can a self-taught artist increase the probability that he or she will become a master?

For any artist to reach master level, you have to live a lifestyle of constant growth and exploration. The ideal is what I once heard an education professor refer to as “self-directed learning.” In self-directed learning, motivation is crucial, because you are on your own. There is no one standing over you to encourage you to keep going or to give instructions on your next step. Self-directed learning is most beneficial when it’s motivated by a goal – a reason to continue learning for the long term. Clear goals, along with curiosity, push creative people to explore what may seem like disparate ideas and experiences that they then internalize into a focused, individual point of view.

My self-directed learning journey began in earnest in 1972, at the beginning of my full-time career as an artist, when I was listening to an interview on National Public Radio about the role of the artist in society. One comment touched me. The speaker said, “In order to do excellent work, you have to know what excellence is.” She went on to say that experiencing excellence in all areas of the arts – decorative arts, painting, sculpture, literature, poetry, music, architecture – will help you build a broad foundation to inform your work. This was an epiphany, because I intuitively knew that to be a master paperweight maker I had to educate myself beyond the world of contemporary paperweights. I had to find ways to bring my interests and ideas to the paperweight category. This discovery inspired me to seek out knowledge that would complement my creative journey. I began studying antique French paperweights to determine how to build on that tradition, closely observing the details of native flowers to interpret them in glass, and listening to great works from the Western canon on audiotapes.

Tell us three books you would recommend that emerging artists read and why.

The Story of Art, by E.H. Gombrich

There are times when the material I’m reading goes over my head and I have to read (or listen) a second time. The Story of Art was an example of this. I persisted and sensed the value of the information, working past the frustration and questions about whether parts of it were important. As I continued reading, I felt fortunate to have been exposed to this wonderfully well-written arts survey. Trust me when I say it’s worth the effort and time needed to understand Gombrich’s overview of art history.

The Story of Art gave me a sense of pride in knowing that, as a maker, I was continuing a great tradition that contributed to the well-being of society, whether or not my work was applauded.

As an add-on, I encourage makers to look at Sister Wendy’s 1000 Masterpieces by Sister Wendy Beckett with Patricia Wright. The captions explaining the artworks are clear and succinct, and offer a very informative and poetic way to experience great work.

Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking, by David Bayles and Ted Orland

Art & Fear is a straightforward, easy read geared toward artists at the beginning of their journeys. The book is rewarding because it touches on the many unique variables that studio artists deal with daily, such as worrying about failure, wondering whether they’ll develop new creative ideas, and finding the emotional stamina to survive as a professional artist. Most creative people are fully absorbed by their own artistic vision and can feel overwhelmed by their struggles. Art & Fear connects its readers to a variety of problem-solving scenarios and advice about artmaking. As someone who spent much of my adult life in the studio, I found it reassuring to know that others share my fears. The authors offer practical advice for maintaining goals and a sense of self-worth.

Another way I overcame my insecurities to succeed in the arts was by reading biographies and autobiographies on other creative people, such as The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, Walt Whitman: A Life by Justin Kaplan, and James Joyce by Richard Ellmann. It’s inspiring to read how other people overcame adversities – often far greater than I have faced – and still created significant work.

Steve Jobs, by Walter Isaacson

Walter Isaacson, in an insightful way, illustrates Jobs’ commitment to quality, innovation, and creative problem-solving. Jobs balanced a creative vision with good design while protecting the integrity of his products with a strategic indifference to the demands of the marketplace – demands that he ultimately reinvented. He invested his emotional energy in creativity and educated the public to have higher expectations for what technology could deliver. After a lifelong commitment to quality in my work, it was sweet to read how Jobs applied his commitment to excellence and originality, and to realize how it changed the world.

Where should self-directed artists go online to educate themselves?

For experiencing a broad range of artworks across multiple disciplines, I recommend visiting Google Art Project, Khan Academy, Artsy.net, and Daily Art Muse.

Additionally, every major museum has portions of its collection and additional resources available online. For students of glass, the Corning Museum of Glass website is a tremendous resource that offers historical as well as contemporary glass works.

TED Talks are another one of my favorite online educational resources. If I’m doing something tedious in the studio that doesn’t demand my full attention, I’ll listen to TED Talks on my iPhone. From my perspective, three standouts among the thousands of great videos are Nancy Callan’s “21st-Century Glassblower,” Salman Khan’s “Let’s Use Video to Reinvent Education,” and Ken Robinson’s “How Schools Kill Creativity.”

In your latest book, Spark the Creative Flame, you wrote “You have to identify what you care about and develop ways of learning that will correlate your studies with your artistic goals.” How should an artist go about identifying what he or she cares about?

I cannot answer that question for other people. I can only describe how I connected my core interests with my aptitude.

As a child, I loved playing in the woods and building things with my hands. But as an undiagnosed dyslexic in the 1950s and ’60s, I had no success in the school system. Because I was viewed as a failure in that setting, I had low self-esteem. Fortunately, I followed my natural aptitude for working with my hands and pursued a trade at Salem County Vocational and Technical Institute (now Salem Community College). In the scientific glassblowing program, I felt the value of education for the first time. As I mastered my craft, my need to be creative became more apparent. I sought ways to satisfy my creative need with my hand skills. When I encountered the Millville Rose paperweight, which was considered the crown jewel of the South Jersey glass tradition, I became very excited by the possibility that I could figure out how to make flowers in glass.

Looking back, I now see how my childhood love of nature and my talent for making things with my hands came together in a way that shaped my life in a very positive way. Though I didn’t know it at the time, my quest to pursue excellence in floral paperweights gave me a vehicle to reach my full potential as an artist and a person.

You’ve written, “The creative journey is fraught with endless anxiety” and that a healthy sense of self-worth can help an artist guard against jealousy and withstand criticism. How should an artist go about developing that sense of self-worth?

Enhancing one’s sense of self-worth is a personal effort. In my career, I’ve sensed a heightened sense of self-worth when I’ve discovered new ways to be creative. For example, after much experimentation and failure, I recently perfected techniques to suggest fuzz on the skin of fruit. Achievements like this sustain my ego, regardless of what is going on outside my studio. In other words, by focusing on my personal vision and spending my days developing techniques to execute that vision, my self-worth is predicated on personal creative successes, not on comparing my work and achievements with others’.

Where can the self-directed artist find community, to avoid feeling isolated?

It’s important to be connected to a creative community. You can form beautiful friendships; furthermore, conversations, seeing others’ work, and visiting artists’ studios can broaden your perspective and advance your artistic maturity.

Living and working in southern New Jersey, I have benefited from proximity to WheatonArts, the galleries and museums in Philadelphia – even Washington, D.C., and New York City. I recommend that emerging artists connect with local cultural centers and public-access studios and attend gallery openings and museum exhibitions. And it’s more than just showing up. To take full advantage of these experiences, you need to actively participate in and engage with the cultural organizations in your region.

These organizations thrive on active participation, and the more of yourself you share, the greater the benefit to your artistic growth.

Monica Moses is editor in chief of American Craft.