American Made, American Maker

From American Craft Inquiry: Volume 2, Issue 1

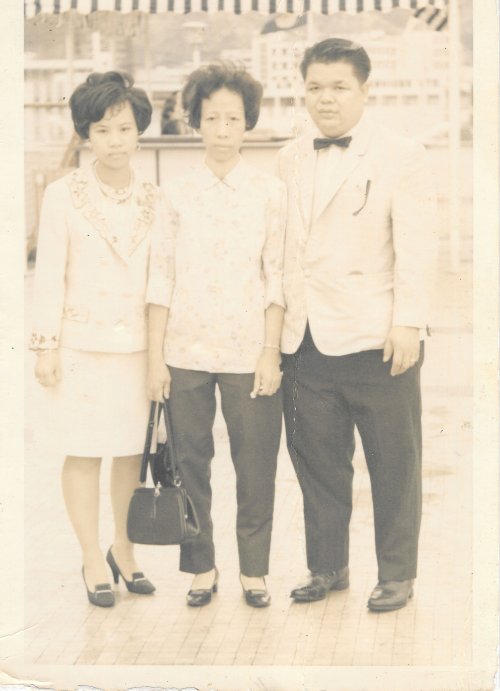

Both of my grandmothers were factory workers. Paw Paw, my Chinese grandmother, watched her family oppose the Communist party in China and lose everything. They left mainland China for British-controlled Hong Kong before arriving to the United States as refugees. Paw Paw worked in a sewing factory, located deep within the alleys of Chinatown, for an American retailer. She often brought sewing work home for extra money, her hands in the constant path and rattle of an industrial sewing machine. When the other women on her line decided to become American citizens, she did too.

My American grandmother grew up in Pennsylvania and lived in Ohio. Grandma bought her first house when she was 19 years old and was just one of a handful of women who worked the assembly line of a car manufacturing plant. Her life did not come without difficult struggles, and she cried every time she told me the story of how her mother gave her away as a baby. She worked on the plant floor for decades, her hands adapting as cars and the assembly-line work modernized with computers and automation.

My grandmothers faced poverty, political and social oppression, and personal trauma. Eventually, though, they both worked with relative security and retired with pensions. They were both tough, independent women during a time when women weren’t supposed to be either. Their lives were confronted with questions and statements that diminished them: “Come back when you get your husband’s permission” or “We speak English in America.” Much of my work focuses on the conflict between my two radically different cultural identities, Chinese and American. I deal with the constant question “What are you?” But my past comes together in the muscle memory of the assembly line. I feel that struggle deep in my body, in my DNA, but I also feel my grandmothers’ hope.

My grandmothers exemplified the concept of “American Made,” the height of American manufacturing. Now the factories are long gone, and that way of life is over. In its place rose cheap materialism, economic exclusion, and globalization. We created the system of faster, cheaper, and more disposable. Now we are in a period of artisans and the craftsperson, where American Made has become American Maker. More and more Americans are choosing to work locally, independently, and with their hands. The slow process and origin story are part of the experience in living with a crafted object. (We’re still working on the relative security and the pension, however.)

In the summer of 2016, I visited a 50-year-old abandoned ceramic supply store and factory in San Antonio, Texas. Digging through thousands of plaster slip-casting molds, I found the naked lady cup mold. I was familiar with these cups, typically found in tacky souvenir shops. My first reaction was to take the mold so no one would ever make this derogatory object again. It sat in my studio for months. Then I heard Donald Trump’s now infamous Access Hollywood interview with Billy Bush, bragging about his objectification of women and sexual assault. Like many women, I decided to grab back and retake ownership of the word “pussy.”

The first Pussy Power Cup I made was personal, a way for me to celebrate what I thought would be the historic election of our first woman president. A video of the cup on Instagram went viral overnight, which was so empowering and uplifting for me. When Donald Trump won the election, it triggered deep unconscious memories of my grandmothers’ pain and hardship, and released a frustration that we hadn’t overcome more as women. This video became my trigger point, and I decided to make more cups and donate the proceeds to Planned Parenthood.

Over the next weeks and months, I felt an increased sense of urgency to create change, to manifest a powerful opposition to our new government. When I couldn’t talk or think or listen or read any more – my hands took over. My hands were stronger than my voice. I saw objects as language, as equivalent to words, and knew I needed to make more.

I opened the Porcelain Power Factory on Inauguration Day 2017. It is an extension of my art practice that reclaims the past lives of objects to bring social awareness to causes we need to fight for.

I research and obtain ceramic objects from functional wares, image decals, and figurines that in past and present-day contexts are insensitive and offensive. I take the history of these objects and remake them to give underrepresented voices a sense of power and ownership in their future. The Porcelain Power Factory allows me to dedicate part of my practice as an example of activism in hopes the work will reach a wider audience and initiate a larger dialogue. It is my hope that the Factory will only be open for four years, possibly less.

With my one-person factory, I am honoring the hard work, fortitude, and dreams of my grandmothers. I am continuing in the tradition of being an American maker and I am helping to define what that means today. The Porcelain Power Factory – handmade, well-designed, and conceptually rooted in feminism and social justice – is my way of exploring how social enterprise informs consumerism and material culture.

View Issue Three purchase issue