Five Questions Salon Edition with Dr. Amy Elkins

The ACC Library Salon Series returns this spring with a full slate of lectures that explore the international side of craft and making. On March 8, Dr. Amy Elkins, a professor of English at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, will share how needlepoint was used by authors and poets in the 20th century. We asked her to tell us more about her research and what she'll be discussing.

Tell us a bit about yourself and your background.

I teach 20th-century and contemporary British-, Irish-, and multicultural-literature at Macalester College. I became fascinated by archives, books as objects, and under-studied craft forms during my MA at the University of Virginia, which houses the Rare Book School. I finished my doctorate in English at Emory University, where I wrote my dissertation on how women use craft processes and media as nonviolent critique in literature. Craft and storytelling have always been linked for me. I grew up in Hot Springs, Arkansas, in a family where storytelling was a deeply ingrained part of the culture, and my mother (an extraordinary woman) taught me to sew, cross-stitch, and paint as I was learning to read, and those things never untangled in my imagination. I studied English and Studio Art at Hendrix College, and as I moved through my higher education, I realized that the same linking of narrative and craft was important for many women writers and activists. It's a timeless, creative conversation that unites people across race, culture, and class, and I'm interested in how something so personal can also be so brilliantly collective.

Your research, and what you’ll be talking about next week, revolves around the 20th-century, avant-garde poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle). Can you give us a little background on who she was and her significance?

The most famous story about H.D. is that in 1912, the extremely influential poet and editor Ezra Pound submitted some of her poems to Poetry magazine, which was probably the most important poetry publication at the time. He signed her name as "H.D. Imagiste," and that marked the beginning of imagist poetry in English. H.D.’s full name is Hilda Doolittle, and although she was born in Pennsylvania, she lived her adult life in Europe and spent World War II in London. She lived an incredible life – studying with Sigmund Freud, for example, while mixing with important literary figures and developing a deep knowledge of psychoanalysis and mysticism. She’s significant because she wrote in masterful, innovative ways about how women think of themselves in society. I’m most fascinated with H.D. and her work because she was deeply interested in the ways women make their own stories and pass them down through history.

What about H.D. drew you to her and her poetry as a research subject?

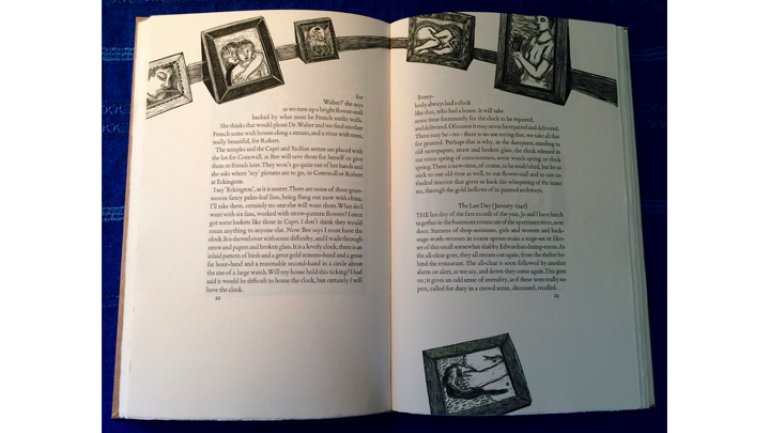

H.D.'s poetry is so beautiful and intricate; it's a lot like a tapestry – many layers and knots full of history and powerful images. As much as I love the poetry, I grew even more interested in her work when I started reading her prose and learning about her life during World War II. It was a contemporary artist's work that made me fall in love with H.D. Dellas Henke illustrated a fine press edition of H.D.'s World War II account of the Blitz called Within the Walls. Published by Windhover Press (1993), the book included engravings by Henke that brought her work to life for me. I wrote to him to ask about the experience of doing the book, which began years of friendship and letters about art processes, Samuel Beckett, bird sightings, and the life of the mind. Those conversations – and that particular book – were the real start of my work on H.D.

It sounds like H.D.’s needlepoint work isn’t incredibly well-known. How did you end up incorporating that element into your research? Where has that led you in terms of new discoveries?

It's not well-known at all. The story of the needlepoint works' discovery is the basis of my talk – so, without giving too much away, I'll say that before I started my project, not even H.D.'s family really knew about this body of work. I'm very attuned to writers who think not just about art, but about the craft dimension of artmaking. I had a strong hunch that she had a craft practice. In terms of new discoveries, the biggest change I noticed in my research after finding the H.D. archive was that I became more fearless about connecting with people who make things. I also trust my gut more.

Needlepoint is a craft with a long history. What have you learned about needlepoint that is most fascinating to you?

The most fascinating discovery I’ve made is two-fold: The history and stories surrounding needlepoint are so deep and rich that artists and writers have a lot to draw on. I've been most fascinated to see its persistence as both a material practice and a metaphor for making, repair, and connection. Perhaps for that reason, people often have a really intense reaction to seeing and talking about needlework. I remember one audience gasping with delight (in unison) when I showed an image of a needlepoint, while other people experience nostalgia, disdain, or confusion. I think a lot of contemporary artists tap into that range of impressions by using needlework when they want to call attention to a particularly significant, personal issue.

This activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund.