Growing Up with Glass

Sculptor Alex Bernstein's parents modeled the artistic life, but he still had to find his own way.

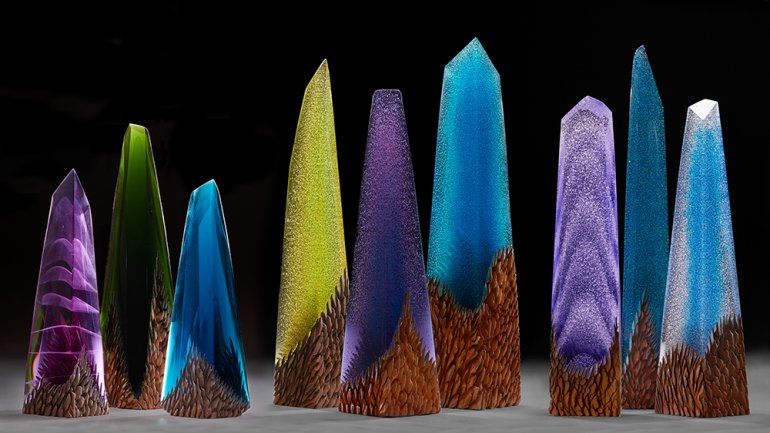

Known for his majestic cast-glass sculptures, often incorporating metal, Alex Bernstein took a while to find his artistic path. Raised near Penland School of Crafts in western North Carolina, with Harvey Littleton and other studio-glass luminaries nearby, Bernstein learned to blow glass as a youngster. He worked as an assistant to glassblowers in the region through high school but found the work creatively limiting. Curious about people, he earned a psychology degree in college but was discouraged by his first job in a psychiatric ward for children. Ultimately, in the late 1990s, he entered the MFA program at the Rochester Institute of Technology; there, working with mentors Michael Taylor and František Janák, Bernstein, 45, discovered casting and cold-working and began making sculptures like those he’s known for today.

What’s not so obvious in his path is the role of his parents, glass artists William and Katherine Bernstein. The elder Bernsteins always represented one possible career path, but Alex knew their relaxed approach to their careers wouldn’t work for him. After graduate school, equipped with new skills and encouraged by models such as Taylor, Janák, and Brent Kee Young, Bernstein embraced life as a sculptor. We asked him to look back on his earliest days as an artist.

How would you describe your parents’ role in the career that you enjoy now?

Both my parents are glass artists, and I’m a glass artist, so it’s hard to not give them most of the credit for that. But I think the most important thing is that they raised me to be a curious, sensitive, and empathetic person, which has helped my art-making process.

How does being empathetic and sensitive help you as a maker?

I’m a sculptor, and it’s a passion-driven pursuit. Curiosity helps drive me. Being sensitive is a really painful thing to be, but it’s who I am, and it means that I am not able to sleep at night when my sculptures aren’t working out as I would like. I never really like anything I make, because I always want to make it better. I’m never like, “Oh, I love this piece! Everybody’s going to love it!” The sensitivity comes in, in my making process, with color and texture and form.

It sounds like your parents instilled you with a drive for excellence.

Yes. But maybe I brought that on myself, actually. Both my brother and I are high achievers, and not that my parents weren’t, but they were more laid-back. My brother and I almost rebelled from their laid-back ways – “We have a cabin up in the woods. But we don’t really care if we make a living or not, because we’re gonna grow a garden.” I remember early on, saying, “Dad, did you consider how you were going to make a living, when you started out as an artist?” And he said, no, not at all.

On the other hand, my brother is a doctor and did his training at Harvard and taught at Harvard Medical School and is highly successful. I race a bicycle, and I work really hard. Both my brother and I strive for excellence, and I think my parents strive to make a happy life. I don’t want to say my parents didn’t work hard, because they did. But they also really tried to enjoy life and still live a relatively simple life, hiking every afternoon, playing tennis, and gardening.

When you were growing up, what were your parents like?

There were always books, and my parents had a subscription to the New Yorker. Intellectually, they were stimulating. There was always classical music, and music and the arts were just a way of life. My parents were amazing cooks — I’m kind of a foodie, and I got that from them; my dad would make pasta from scratch, and my mom would bake bread. And they also had a huge social circle, and most all their friends are artists.

What set us apart was that, no matter what, we were different. I grew up in rural North Carolina, and I am Jewish with parents who are artists. And being Jewish in a very Southern Baptist region — I was born and raised in the South, in Spruce Pine, North Carolina, which is the town that Penland’s located in – I never quite fit in. People would ask, “Where are you from?” I’m like, “I’m from Spruce Pine.” “No, where are you really from?” And I’d say, “Well, I’m Jewish.” And they’d say, “Oh, I figured.” I was like, “What? What do you mean?” I grew up in a place where I never quite fit in.

And people would ask, “What does your dad do?” “He’s an artist.” “Yeah, but what’s his job?” “He’s an artist.” “But what does he do for a living?” “He’s an artist.” Nowadays, that’s embraced a lot more. Certainly, I can go to a restaurant in Asheville, where I live now, and say I’m an artist, and half the restaurant’s like, “Yeah, me too. We’re all artists.” But I grew up close to Spruce Pine, and 40 years ago, when you said that you were an artist, people still scratched their heads. They didn’t understand it.

When I was a kid, I was really jealous of my friends who had trailers, because they were carpeted and nice, and their family worked at the local factory. I was like, “Oh, wow, I wish my dad worked at the factory,” because then I wouldn’t have to explain myself.

That desire was short-lived, because later I learned to embrace the fact that I was just different, being Jewish and having parents who are artists.

You’ve said that you were a creative child. How did that manifest itself?

Well, I remember vividly, my parents were having an addition built onto our house, and there was a big pile of scrap wood, and I remember taking all of the wood out of the trash, much to the chagrin of the contractor, and starting to make sculptures out of it, nailing things together. I would make feet for the sculpture and then add other 2-by-4s to it, and then a piece of plywood would be hanging off the top. That was at an early age.

I remember being at Harvey Littleton’s studio as a kid, and I actually have a vitreograph that I made at Harvey’s. I also have an image of me, age 7, lampworking, working with glass. I remember being 15 or 16 and making a stuffed chicken breast.

You made your first glass piece as a kid. How old were you?

I have a little drinking glass or piece of glass that I was 4 or 5 when I made it. I was literally flameworking. And honestly, being a father, I can’t believe my parents let me have a torch, and I was melting glass, presumably unsupervised. Mom! What were you thinking? My son’s 6, and wouldn’t let him anywhere near a hot torch. But I guess I made it through OK.

Did they teach you how to use the torch?

Their lessons weren’t necessarily about “This is how you do this.” Early in the game, I think, my dad probably taught me how to gather some glass out of the furnace and make some things, but mostly we would talk concepts, more like formal critiques about work that I was making. I learned their process by assisting them during summers, through high school.

But you didn’t see yourself following in their footsteps.

Both my parents are very much self-taught. When my dad started out, there weren’t really glass studios. People were very much just figuring out how to do things. And now you can take classes with somebody that studied Italian techniques, and you can really learn firsthand. Back then, it was not like that.

Also, I was concerned about making a living, unlike my parents. I literally grew up with stacks of American Craft laying all around our house. And I knew, if there was a magazine that sold ads, and galleries were buying ads, that there had to be a certain amount of commerce; otherwise, none of this would work. So I knew there was a way to make a living.

Then my parents got into utilitarian work, where they were making goblets and functional work for Saks Fifth Avenue and Henry Bendel in New York City. They very much found their way with that and were able to support the family. Early on, things were really touch-and-go, and we definitely grew up with modest means. Once they got accounts at Saks, they did better. Through that process, I realized that I didn’t want to have to worry about having money to go to the grocery store.

If you weren’t a glass artist today, what would you be?

I really feel strongly that I picked the thing that I’m best at in this world. When everything is going well, when I’m in my studio making work, there’s really no place I’d rather be. Maybe on vacation with my family. But sometimes on vacation I get really antsy, because I like making things with my hands. Mental health is related to the use of hands, and I tend to get a little stressed-out and not feel well if I can’t use my hands to do something. So, when I’m in my studio and I’m making my work, I feel like this is what I was meant to be doing. If I weren’t a glass artist, I would be an artist using some other material.