Honoring Nature and Imperfection

Roy Staab is a perfectionist. Still, the 75-year-old’s ample energy and artistic vision draw him to nature and its unpredictability. Therein lies Staab’s challenge: how to honor nature, and its fickleness, while meeting his own exacting ideals. The answer is clear in his latest masterpiece, “Nature in Three Parts”– a sprawling, three-part series that closes September 18 at the Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum.

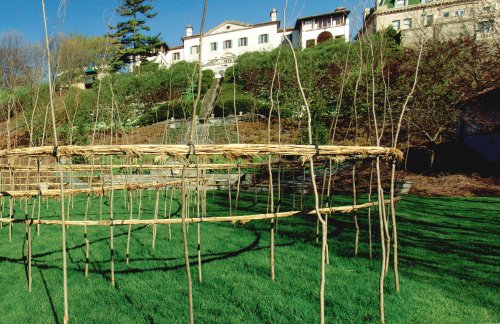

The keynote work, Shadow Dance, is the first commissioned garden sculpture ever featured by the Villa Terrace. After spending around five hours picking sand willow for the piece, Staab discovered that the willow was too brittle to weave, so he bundled and tied it with jute. Working methodically, Staab ascended the Villa’s water stairs to view his work from the museum’s perspective. From that angle, he was unimpressed with the visual impact of willow alone. In short, it was not perfect. So the sculptor turned to his modus operandi: reeds.

Though county officials warned against using them, citing a risk of invasiveness, Staab was prepared; the artist uses year-old reeds – the seeds disperse in the winter and no longer pose a risk.

Determined, Staab visited an abandoned swamp 20 miles west of Milwaukee to collect more reeds, eluding a suspicious factory worker who threatened to call the police. With new materials and a revised plan, Staab directed his attention to his ambitious design – based on formal gardens in Persia, Iran, and France.

Roy Staab's Shadow Dance is carefully constructed of sand willow, jute, and reeds. Photo: Jim Brozek

Staab’s site-specific work is visually appealing and carefully calculated. The sculptor reaches a sort of intrinsic perfection with math – the indisputable arbiter of what is perfect and what is not. Calculations decided the placement of rings between the garden’s obelisk and waterfall stairway. Using the golden mean (a calculated middle ground between two extremes), a compass, and a laser level, Staab reaches aesthetic and mathematical perfection.

At the close of the exhibition, Wild Space Dance Company will perform a site-specific routine, “Into the Garden,” at Staab’s sculpture. Therefore, Staab wanted his sculpture to be sturdy enough to maintain its form during physical interaction. After raising the structure off the ground, he once again climbed the steps to view his work.

It earned his approval, and he saw what he called a “perfection of this horizontal.”

According to Staab, the best view of Shadow Dance is at 2 p.m. while descending the staircase and observing the shadows change, but Staab wants viewers to explore his creation from the ground.

“I like kinetic art, but this one is static,” he says, “and it’s up to you to experience it by descending the stairs and going inside. And to go inside, you have to crawl like a baby to get in the middle and suddenly you’re inside a very large environment controlled by the lines. I invite people to touch it. Yes, the reeds are fragile, but I feel it is part of the living experience to touch and feel.”

The second part of the exhibition, Suspended in Time, is indoors where Staab displays photographs of past installations. To Staab, taking pictures is “the only way to hold on to ephemeral art.”

Suspended is comprehensive and allows the audience to view his other works large-format photographs and videos.

In the final piece of “Nature in Three Parts,” Staab becomes a guest curator for Beyond Baskets, choosing contemporary pieces from art patrons Jan Serr and John Shannon’s collection that reflect his standard of perfection in a different medium.

“I chose baskets that show fine craft because my art had to be fine craft and perfection, and these baskets were the same way.”

Staab’s latest exhibition reflects his recurring theme of perfection in nature. As Staab manipulates reed, willow, and jute to a perfection that will endure, presents records of his rich history of work, and highlights others work as guest curator, he encourages interaction with nature and art all throughout “Nature in Three Parts.”

“My kind of art has to be experienced, and I want people to know it. And I don’t only work for myself. It has to pass by perfection.”

Molly Geisinger is American Craft magazine’s summer intern.