It Is Written

From American Craft Inquiry: Volume 1, Issue 2

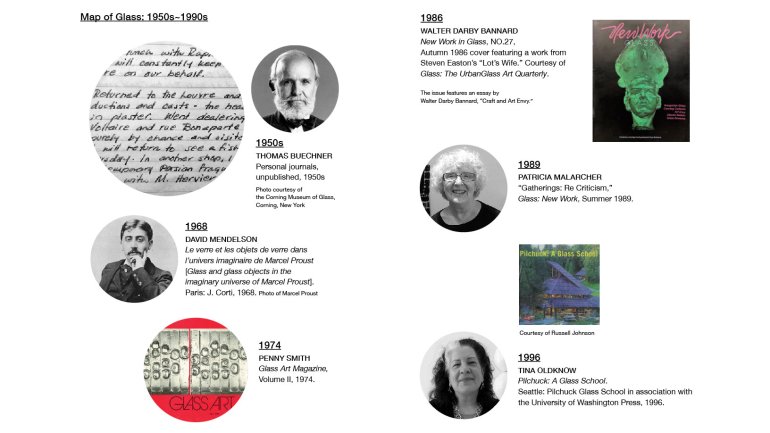

Think of this essay as a map showing a little of the terrain already covered and regions yet to be explored in the rich history of writing about glass in the 20th and 21st centuries, from Thomas Buechner to Kim Harty. The story of glass as a medium for craft and art has been the work of hundreds of writers seeking to capture meaning in diverse ways: They excavate for facts, deconstruct seemingly impregnable narratives, coyly keep secrets or shamelessly reveal them, practice old-fashioned journalism, compose in the codes of esoteric jargon specific to the academy, or oppose those codes in favor of the new vernacular of blogs and social media.

The coverage might seem a little thin in the mainstream art press, but I think that is only because the field itself is so small in comparison with art mediums such as ceramics or painting. But it is thick in the realm of monographs and small magazines and museum catalogues and newspaper clippings, although these are scattered across the country and continents and so can seem inaccessible to all but the most dedicated researchers.

Perhaps because of this dispersion, throughout my career as an art historian and critic specializing in glass, I have endured countless voices at conferences and in publications bemoaning the lack of serious art historical and critical writing about glass. A recent lecture in this vein inspired this essay.

In their 2015 presentation at the Glass Art Society conference in San Jose, later published in the GAS Journal as “The Critical Vacuum,”1 Hyperopia Projects artists Helen Lee, Alex Rosenberg, and Matt Szösz asserted that there is a poverty of criticism in the glass community. They wrote: “The work being made by contemporary glass artists over the past decade requires a more sophisticated address of criticality than in previous decades.” And they claimed: “There is no lack of means to engage in criticality, but perhaps there is a lack of educated voices in our field.” Hyperopia made me ask once again: Is there truly a lack of educated critical voices? Why are so many people so sure that there is a paucity of criticism of glass? One way I found to ease my frustration was to write this essay.

In the old 20th century

I was trained in art history, criticism, and philosophy at the University of Chicago by Harold Rosenberg, John Rewald, Richard Shiff, and Paul Ricoeur, and as a young curator at the Corning Museum of Glass in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I sought writers with a sophisticated critical voice to match that of my mentors. I, too, might have begun my career by bemoaning the lack of critical writing about glass, if not for a discovery in a bookstore. David Mendelson became my touchstone. His book, Le verre et les objets de verre dans l’univers imaginaire de Marcel Proust (roughly, Glass and Glass Objects in the Imaginary Universe of Marcel Proust) was published in 1968.2 It is a brilliant critical analysis of why glass was central to Proust’s universe. But Mendelson was not alone, and throughout my career I have enjoyed reading critical essays by many other great writers on glass. I did not spend my time complaining about the writing: If I saw a need, I tried to fill it – for example, by asking the modernist critic Clement Greenberg to write and lecture about glass and by delving deeply into the archives looking for good unpublished writing. This is nothing original to me; it is in the training of all art historians and curators.

So let’s see what has been written about glass.

The diarists

In 1953, Thomas Buechner, the founding director of the Corning Museum of Glass, was given a generous budget and charged with traveling around Europe, acquiring objects for the new museum. What a privilege!

He kept a journal (which remains unpublished3 ), with all sorts of tantalizing notes. He described, for example, examining the famous ancient Roman Lycurgus Cup on March 19:

Spent an hour with Lord Rothschild at Merton Hall, the oldest building in Cambridge and his home. The Roman vase is a very strange piece. Like Schmeltz glass, it is green in reflected light and red in transmitted light. … Lord Rothschild believes it to be 4th-century Roman and according to him this is verified by Ray Smith and Donald Harden. Although the carving is good, there [are] the same stylistic problems (and vague solutions) as we have had with the Morgan cup. Lord R. would sell it for £15,000.

Notice the critical component to this paragraph: “same stylistic problems (and vague solutions).”

Later, while in Paris, Buechner had an encounter with a precursor to the studio glass movement. He wrote on March 23:

Went dealering along the Quai Voltaire and rue Bonaparte – Met Jean Sala purely by chance and visited his atelier. … [where he] made a rooster. I was amazed. He does it completely alone, rotating two irons at the same time, transferring to punty alone, blowing one section while he marvers the other. It was a real treat. I bought a small fish by his son for 2,000 and a kiwi by himself for 8,000.

What I find significant about these examples is Buechner’s clear interest in quality and style as it relates to glass; and his highbrow critiques are followed closely by price, injecting a level of practicality you don’t see in most art criticism.

Other writings of the studio glass era remain tantalizingly out of reach because they are in restricted archives – for example, the extensive cache of journals, highly detailed, at times very personal, of the flat-glass artist Richard Posner, housed at the Rakow library at the Corning Museum of Glass. A positive way to look at this is that, just as archaeologists working today have made decisions to set aside certain prime areas of major sites for future generations to excavate using new techniques, the possibility of “excavating” fresh material from the archives may prove a great inducement for future young scholars.

The earliest Glass Art Magazine

From the start, there has been a brainy side to glass coverage; for example, in Glass Art Magazine, edited in the 1970s by Albert Lewis, with Ruth Tamura as associate editor4. In working on this essay, I was excited to find the writings of Penny Smith but also embarrassed that I had not discovered her earlier in my career. Smith held a master’s degree in the sociology of art and was a member of the Berkeley Poets’ Commune, and her writing anticipates by decades many of the questions explored by later critics such as Donald Kuspit, as well as by commenters on social media. She wrote a regular column for the magazine, covering topics such as “Art and Survival,” “The Role of Artist in Society: Conscious and Unconscious,” and “The Artist as Soothsayer: Is the Artist Really Ahead of the Times?”

How current her words seem today:

People sometimes [act] … as if art itself had nothing crucial to do with human life and survival. I would like to suggest the opposite: that art itself, its creation and its appreciation, is integrally tied up with our survival and always has been.

Some artists are spokesmen for a particular lifestyle and world view. … One uses art for social fusion while the other uses it for revolution.5

There is poetry in that.

If the artist can then use art as a consciousness-raising activity and is instrumental in moving people with him, he is more than a soothsayer. He is a revolutionary.6

Exactly what we long for today.

What adds luster and depth to her writing is a recognition of the universal longing for a healthy balance and moderation, what some today call the “on the one hand, on the other hand” approach to life and art. Smith writes that the artist must learn to understand how the public sees itself as much as what they want to “look at or hang on their walls.” “At varying times people will either find crudeness appealing, as a sign that the article was made by hand and not by machine, or they may be looking for excellence in control as an indication of self-discipline.”7 For our feverish, polarized political climate, Smith offers words that can heal, if we will only listen.

Museum journalists

Important writing suffers when it languishes in obscurity. An example is issue XXII of The Museum Journal, published by the West Texas Museum Association in 1983.8 This remarkable monograph documents an exhibition and conference at Texas Tech University. Paul Hanna, the guest editor, remarks on the contribution by Elizabeth Skidmore Sasser (1919 – 2005) tracing the history of the studio glass movement in America: “Oddly, this is apparently the first time such a summary has been done.”9

Sasser was a professor of architecture at Texas Tech. In her essay, “New Glass in the United States,” she wrote:

In retrospect, it is easy to establish an analogy between the Abstract Expressionism of the ’50s and the revival, in the ’60s, of an interest in glassblowing as an art and a personal way of expression. Both explored organic forms, frequently conceived in liquid colors and luminous transparencies, although opaqueness and layering of textures were common in both media. Both used trailing lines of color, like the threads which centuries of glassblowers have dripped over their work. Glassblowing, like painting, emphasized the concentration of the whole body in the poetry of the action.10

I have to admit I am jealous that she made this apt comparison between mediums quite a while before I began making it myself. And how many other writers have made the comparison since, without sourcing it to Sasser?

Kim Smith, who taught art history at Texas Tech, contributed an essay about “Glass as Medium and Metaphor: Three Episodes in the Dialectics of Transparency and Opacity.” She serves up a nice metaphor herself at the outset: that it is “not uncommon” for written texts themselves to be described as transparent (implying that the meaning behind the words is readily evident) or opaque, “suggesting an impenetrable surface.” She works her way from the severe geometric precision of Peter Behrens’ designs for a goblet to an analysis of Robert Smithson’s 1969 Map of Glass, a heap of broken glass in the shape of the mythical Atlantis. She selects a lovely poetic quote from Smithson: “Outside in the open air the glass map under the cycles of the sun radiates brightness without electric technology. … Like the glass, the rays are shattered, broken bits of energy, no stronger than moonbeams. … A stagnant blaze sinks into the glassy map of a non-existent island.”11

Smith ends by considering the work of Dale Chihuly, where there is “no inner geometry or plan to be discovered,” concluding that “these objects severely restrict any access to their interiors in the broadest sense of that term. Yet, in a very important sense, all remains visible.”12 This brings to mind Kuspit’s later psychological analysis of Chihuly, as cited below.

Art in crisis?

You want negative criticism of glass? Ground zero is the article “Decorative Arts: ‘Americans in Glass’: A Requiem?” by Robert Silberman for Art in America.13 In it, Silberman reviews the exhibition “Americans in Glass,” organized by the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum.

Silberman writes: “If ‘Americans in Glass’ is something of a disappointment, that is no doubt partly because the heady early years of the studio glass movement are a difficult act to follow” and that “the crisis revealed by ‘Americans in Glass’ … reflects a certain aimlessness within the art world as a whole.”

He remarks that the “most striking thing about the 1984 ‘Americans in Glass’ … is not the works of art on display, but the statements in the catalog by [the] jurors …” For one juror, J. Stewart Johnson, “the current exhibition offers ‘little wit, little flair, little real excitement.’ ” Another, painter Julian Schnabel, “added that inclusion should not spoil the artists selected, and that if an artist was discouraged by rejection and gave up, perhaps the discouragement was justified.” Juror Helmut Ricke “proclaimed that the goal of the studio glass movement should perhaps be to render itself obsolete as a movement …” Silberman himself concludes that the exhibition “raises doubts about the future of a movement that only several years ago seemed on the edge of a major breakthrough.”

In the years since this review, there has been a steady procession of articles and lectures critical of studio glass, by writers from Janet Koplos to Maria Porges to Adriano Berengo.

There were notable positive voices writing about glass in the 1980s as well. Richard Shiff (Regents Chair in art history at the University of Texas at Austin and co-author of the catalogue raisonné of the works of Barnett Newman) was a panelist at the Glass Art Society conference in 1982, where he suggested that:

The prospects I think are actually quite favorable for the glass artist today. … Why has this come about? I believe it has something to do with the modern concern for unconventional art and return to a naïve and ever-primitive vision – naïve and primitive in a very positive sense. A kind of ideal return to a purer state of being. Painting and traditional sculpture are often seen as being laden with convention. For many artists, nearly all painting and sculpture seem academic. It seems impossible to create with a new beginning within these traditions. The crafts, however, seem to offer new materials and new techniques. … It is as if the familiar materials of the traditional crafts become freshly unfamiliar when reconsidered in the context of fine art.14

On the same panel was the noted critic Paul Hollister, who wrote about glass as a freelancer for publications including the New York Times and who was never afraid to call it as he saw it:

I don’t think that glass workers should have this tremendous goal of size increase in mind all the time. I don’t think size is that important. … If it’s barn size, it’s great. And then we start doing to the landscape what the strip-miners are doing, but doing it under the name of art. I think pieces have a certain size that is just right for them.15

Florence Rubenfeld’s review in Glass: New Work of a show of pedestal-scale glass at Anne O’Brien Gallery in Washington, DC, in 1986 seems to provide a response to Hollister’s comment about size in glass: “The fact is that, in a curious way, the scale and content of this work may be filling a poetic void created when fine art abandoned intimate and personal subject matter in favor of ‘larger issues.’ ”

Patricia Malarcher produced an overview of the state of glass criticism in “Gatherings: Re Criticism” in 1989.16 She asked: “What is the basis for competence in criticism?” and noted that Kuspit “suggested that all art is in need of better criticism,” which, according to the eminent critic, should be less about the “imprimatur of good taste” and more about an investigation of the artwork’s “critical relationship to nature, society or art itself.”17

Malarcher concludes with a reference to the aesthetician Nelson Goodman, who “suggests that the question ‘What is art?’ might be replaced by ‘When is art?’ The implication is that the same object can be art at one time and something else at another. This suggestion has been met with controversy but nevertheless shows cracks in old categories.”18

While Goodman was wondering “when” is art, Kuspit was, by the end of the 20th century, questioning its ability to address issues of mental health and finding favorable answers in craft mediums. In his book Chihuly: Volume 1, 1968 – 199619 he wrote: “Glass has the power to alter consciousness.” Recognizing that “oceanic experience is necessary for psychosomatic health” and that society is always undermining the individual’s sense of self-worth, Kuspit saw that “Chihuly’s paradisiacal environments” can rejuvenate us. He continues:

One of the tasks of art … is to express and restore the individual’s primordial sense of intrinsic value. It does this by facilitating … an in-depth oceanic experience, that is, a return, in spirit, to the … womb … to childlike innocence, and to an unself-conscious feeling of well-being. Such innocence and well-being, with their implication of psychosomatic health and their sense of responsive delight, radiate from Chihuly’s forest-and-sea environmental installations.

By finding a grounding purpose in mental health, Kuspit was able to show how useful glass can be as a medium for art.

Early in the 21st century, the critic and Art in America contributing editor Janet Koplos spoke to the Glass Art Society about criticism.20 She admits up front that “I don’t much like glass” and in her concluding remarks asserts that “glass needs a critic or an advocate to consider its meanings and purposes,” a statement that makes me think that she does not know very much about the earlier writings of individuals such as Kuspit.

Still, I find her candor sympathetic. She tries to find dimensions of glass that are appealing to her, such as the “… distancing, impersonal surface … there may be something about this that’s meaningful for our times, that identifies something about contemporary culture. We do live in an age of image or virtuality, rather than reality.” Koplos also concedes “I don’t think that ‘critic’ equals ‘negative’… it is, frankly, much harder to be negatively persuasive about art than positively.” She finds the artist William Morris offensive for telling empty stories and is critical of Josiah McElheny for burnishing his fine arts reputation while staying mute about his technical skills with glass, lest anyone doubt his place in the fine art world. Regarding Morris, “The crux is that I don’t believe these works, and that’s what it comes down to for any viewer: whether the work convinces you.” I give Koplos points for avoiding the hierarchical types of judgment typical of the 20th century, and, instead, for stretching to build a critique around ideas such as virtuality and believability.

My argument that there is a lot of critical writing about glass but that we have been unaware of much of it was played out on the larger stage of craft in America in 2008, when the dealer Garth Clark began to write and lecture about “How Envy Killed the Crafts” without realizing that a discussion of the same topic took place in the glass community more than a generation earlier.21

Clark wrote:

For most of the modern craft movement’s 150-year life, it has wrestled with a debilitating condition, an unhappy, contentious relationship with the fine arts. … Craft has moved constantly between resentment and envy with the relationship growing increasingly acrimonious as art moved away from craft-based values in the midcentury and closer to post-1950 conceptualism and the dematerialization of the art object.

Clark also accused the craft mediums of being seriously inbred:

And lastly, the autopsy revealed clear indications of incest and resultant signs of severe brain damage. For decades, the tradition in craft was to have a close friend and fellow crafters write one’s reviews. Crafters have written most of the books, curated the bulk of the exhibitions, organized the conferences. Little light was shone on craft from without, much to its detriment. Indeed, as arts movements go, craft is so inbred that it is just one cousin away from becoming a cyclops.

I cannot speak for other mediums, but for glass this is simply not true: We have benefitted from a rather vast array of outsiders descending upon our fair medium and writing reams about it. One of those outsiders was the abstract painter Walter Darby Bannard. Bannard comes to mind in particular because he addressed the same issues that Clark wrote about, but almost a quarter of a century earlier.22 I include a long quote because I find his writing very lovely. If Garth Clark speaks with the fire and brimstone of the Old Testament, Bannard employs the grace and forgiveness of the New Testament.

Is craft art? Is art craft? Are they interchangeable? Can one become the other? Are the differences nonexistent and comparisons invidious? Or will the twain never meet? These anxious uncertainties muddle every consideration of craft esthetics. I think they are false issues, misleading questions met by ambiguous answers.

The root of the confusion is our odd refusal to take art for what it is. Though art is material, it is entirely human. Of all things physical, it best fits Paul’s phrase “labor of love.” It is as close to us as any thing can be, the most personal, the most intimate, the most to do with feelings which represent the best of ourselves to ourselves. We make much of art, but in the wrong way. We make it too important, an object of reverence rather than of simple feeling. We have sanctified it, ritualized it, buried it in huge mausoleums, torn it away from life. We forget how fragile it is, how it could wither and blow away if unsupported by the life force of human feeling.

Craft usually suffers by aspiring to be “art,” either in the making or the appraising. Is this just another snotty put-down of craft by an artist? No, not at all. I could never disparage craft. I have too much love and respect for it. On the contrary, I am arguing for its integrity. My quarrel is with the misapplication of values, with the invidious notion that, if it isn’t art, it isn't much of anything. The urge to be the best is always admirable; the urge to make everything “art” is perverse. It usually leads to bastard forms, forms which don’t amount to much as craft or art. Art envy, in craft and in architecture and in any of the other media – movies come to mind – is misplaced and destructive. Craft does not need to be art; it finds its highest form as craft.

I wish that we could have gotten Garth Clark and Bannard together on the same panel to hammer out common ground, but Bannard died in 2016.

In the early 21st century

But enough of looking back at the rich roots of glass writing at the end of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st. What of writers working today?23 What are their methods, and what do they think we could be doing better?

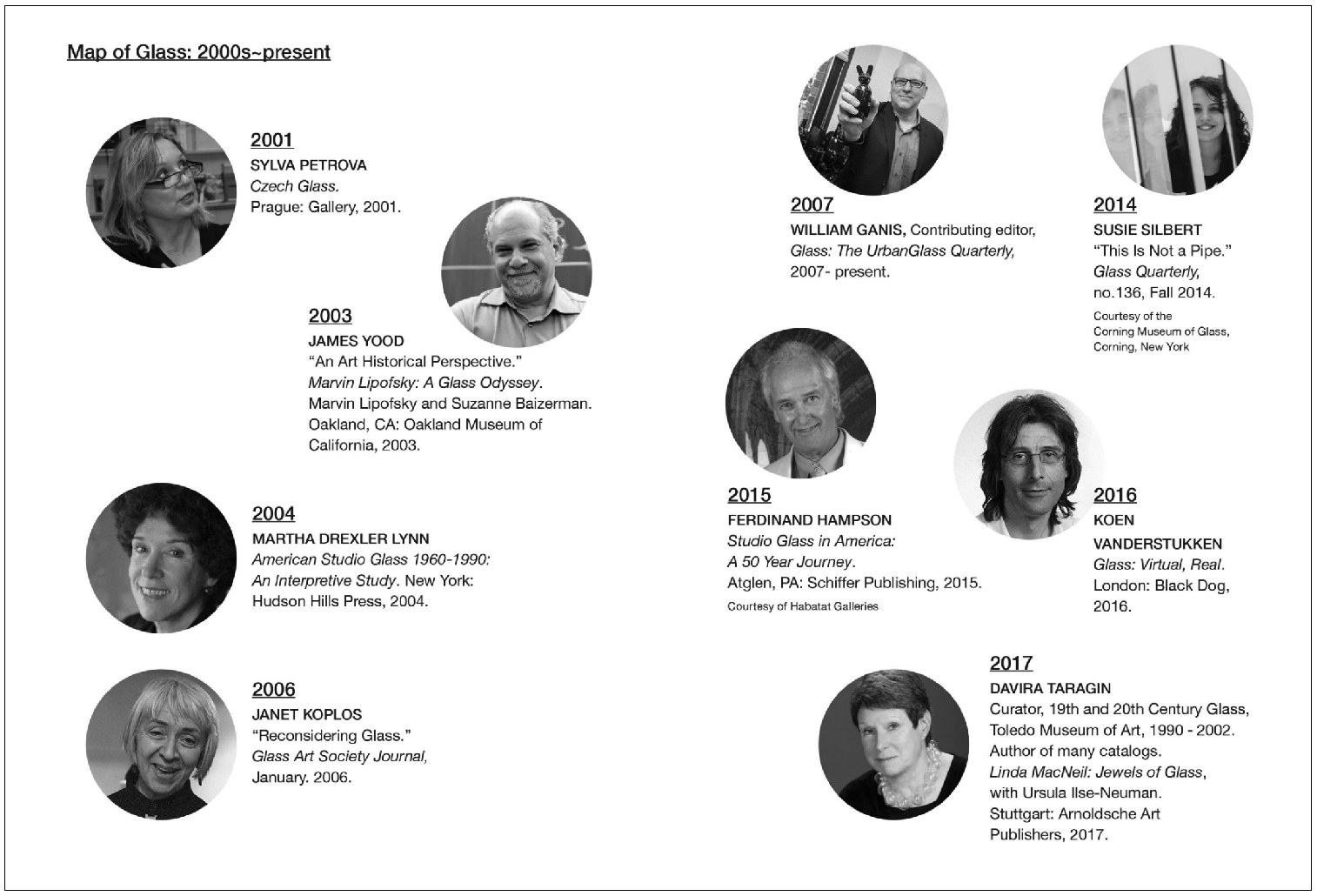

Glass: The UrbanGlass Quarterly has been led by a number of strong editors, including Karen Chambers, John Perreault, and, most recently, Andrew Page, who has encouraged the writing of two notable contributing editors, James Yood, associate professor of new arts journalism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and William Ganis, chair of the art department at Indiana State University.

I caught up with Ganis in March 2017, while he was writing an article for Glass about designed mass-produced glass vs. studio glass and how it has been pushed somewhat out of the main narrative of contemporary glass.

He feels that we as a community are good at monographs about artists who have a certain level of gallery success, and that technical information about the artists is well covered. The great accounting that took place during the 50th anniversary of studio glass in 2012, he believes, was a moment that made us reckon. He speculates that the conference of the Glass Art Society in Venice coming up in 2018 may be another such moment.

By comparison, he says, we are less complete in the areas of art historical and critical constructs as applied to glass – social history, for example. And he remains surprised at how many longstanding figures in contemporary glass have had relatively little written about them, as he discovered when he wrote about Emily Brock. In a recent essay about Stephen Powell, Ganis tried to focus on the experience of the work as opposed to the technique: the optical aspects, illusions, and accidental effects that characterize his work and how these create meaning.

Regarding how he writes about individual artists, James Yood responded that he writes differently depending upon the venue; for example, he writes “differently if the artist is paying for the book or some other entity is.” I especially appreciate Yood’s workmanlike, no-frills approach as a professor: “We tell our arts journalism students that the particular culture of what we do is that we are trained to write to word length, on deadline, for money, and I take all three of those aspects seriously. I never write just for my own satisfaction.

He has some personal preferences – what I see as ethical guidelines: “I never speak to an artist whose exhibition I am reviewing. While I’m happy to interview the artist who is the subject of an article or an essay for a book, I don’t like printing quotes that much; I’m suspicious of them.” And he echoed a sentiment I heard over and over again among the writers I contacted: “Writing is hard; I would never call it a pleasure to know I have a 675-word review due in a few days.”

Marvin Lipofsky: A Glass Odyssey includes Yood’s essay “An Art Historical Perspective.” After discussing Lipofsky relationship to colorists such as Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and California artists including Richard Diebenkorn, Yood zeroes in on what makes him distinctive:

His pieces are not monumental and his color cannot overwhelm us through sheer size. Instead he seeks a subtler intensity, a more pungent approach to color, mottled and concentrated. Glass is especially conducive to this; color is often not applied upon it, but exists within it, part of its very nature, inseparable from form. In Lipofsky’s hands color literally becomes sculpture, and some of the arabesques he performs with it assist in making color volumetric.24

The curator-writers

Tina Oldknow, who retired as curator of modern glass at the Corning Museum of Glass in 2015, says that her deeply researched book about the history of the Pilchuck Glass School propelled her into the world of contemporary glass. But the Richard Marquis book (Richard Marquis Objects) is her favorite. Marquis did the photography; she likes that. The Michael Glancy essay for the book about his work Infinite Obsessions was an interview of a type she wants to pursue further. She wants her writing to be not so much critical as a forum for the artist to talk about the work. Her forthcoming book about Albert Paley is an example. Text sections, such as the one about Paley’s work in glass and metal, will break up the long interview with references.

She enjoys different artistic temperaments. Some artists are deep thinkers and cautious in what they say; others are less complex. She does long taped interviews over periods of several days, which are heavily edited and then “constructed.” Oldknow loves to go off on tangents, which are intended to give the reader a rest from the interview format and also act as a reference. She says her writing tends to be tightly woven, so she wants to pull the weave apart a little with these side stories, a process that began with the Pilchuck book.

In the 1980s, she sought to “formalize” her writing, to get it away from the first-name basis and avoid the “idyll on a horse farm” crafty approach then prevalent. Of course, now everything is once again more informal. Teamwork tends to dominate museums now. The challenge for curators, as she sees it: Where should your voice be in the institution? In the exhibition labels, less so; in your own books, more so. But artists have strong individual voices, and the best way to bring that out is through an interview.

Oldknow weaves interviews together exquisitely to reveal the philosophical differences and opposing points of view common in 1973, as in this discussion from her book about the Pilchuck Glass School:

What was essentially open space in 1972 is now dark and increasingly impenetrable. …“The trees have grown 60, 70, 80 feet since we first came there,” says John Landon. “I don’t even recognize the school anymore.” Even the view at Inspiration Point is disappearing: Newcomers to Pilchuck can never know how open those incredible vistas once were …

The two factions that had formed at Pilchuck the previous summer – the glass followers of Dale Chihuly and the multimedia contingent backing Buster Simpson – had returned in full force in 1973. … Chihuly argued for more focus on the hot shop and getting work done, while Simpson wanted a greater awareness of environmental and social issues.”

Oldknow quotes Ruth Reichl: There was “a struggle between this vision of Pilchuck as a major glassblowing center and Pilchuck as a place to try living in the forest. … And they were competing visions.”25

Davira Taragin has been a curator at the Detroit Institute of Art and the Toledo Museum of Art, and in those capacities has written many museum catalogues. She observes: “We continue to have problems in terms of writing in general, not just in terms of glass. … Some writing is too abstruse, for example.” She finds the writing in the arts section in the New York Times exemplary. At the Detroit and Toledo museums, she was taught to write for readers with a sixth-grade education level when preparing exhibition labels.

And yet, she says, there is also the problem of the absence of footnotes in many publications. “Curators have a responsibility to do their due diligence in terms of research.” Writers she admires include Martha Drexler Lynn: “Her research is impeccable, and there is meat in terms of what she writes.” We have a responsibility to think in terms of 100 years from now, she says. “We are now so involved with the new that we are forgetting our history. We need these in-depth studies [referring to her new book and exhibition on the work of glass jewelry maker Linda MacNeil] . … Capturing the history is the most important thing right now. We need better documentation, for example, of patronage and gallery dealers.”

This essay focuses mainly on American writers, but I include one European correspondent, Sylva Petrova, to indicate the richness of the traditions there as well as the differences and similarities of roles played by writers. Czechoslovakia was at the forefront of publishing about contemporary glass when it launched the Czech Glass Review in 1946, which published works by many leading critics such as Arsen Pohribny and Milos Volf. Petrova has been a leading curator and writer in the Czech Republic for several decades. She feels that in Europe, what she calls “non-glass” people – those trained in the general history of art and who entered art museums and other institutions – have played an important role as observers of the scene: “Their essays, books, and exhibitions were absolutely crucial for the development of studio glass in Europe, especially in the three last decades of the 20th century.”

Among them she includes Jean-Luc Olivié, Alena Adlerová, Betyna Tschumi, and the leading figure Dr. Helmut Ricke, who established the magazine Neues Glas – New Glass. Petrova sees his exhibition and the book Neues Glas in Europa – New Glass in Europe from 1990 as essential: “He formulated specific features of European modern glass there, defined trends since the 1950s, etc.,” she says. “I have never read something so brilliant.” Today, Petrova is heartened by the increasing interest in PhD glass studies in the United Kingdom, Latvia, Romania, Slovakia, and many other countries.

Jaromira Masikova is one of the crucial early writers that Petrova most likely had in mind. Discussing the monumental work of Stanislav Libensky and Jaroslava Brychtová shown at Expo ’67 in Montreal, she wrote that, “This is a sphere in which Bohemian glass is reaping international success. … Their pioneer work elevated glass into the region of genuinely free creation where glass never appeared before with such perfection.”26 When terms like “pioneer,” “genuinely,” and “perfection” are used today to describe glass artwork, I tend to be very skeptical, but coming in 1967, her observations and vocabulary are spot on.

Petrova’s most important work is Czech Glass (Gallery Prague, 2001), which was unfortunately on the market for only seven months when the entire print run was destroyed by the enormous Prague flood in 2002. The good news is that an expanded edition will appear in 2018, covering the years 1945 to 2015.

She observes that today, frequently, many writers conclude “the glass object (sculpture) to be dead”:

It was replaced by the installation or even more pointedly, the concept. In my view, nobody who is educated in the history and theory of art can take such an argument seriously. New disciplines are entering the established art fields regularly. And the reaction is always the same: Everything existing before that new development is going to be pronounced dead. In reality, it has never ever happened! Photography never killed portrait painting, video and installations never pushed out classical forms of sculpture. … In glass, the progress will confirm the same. All of the glass disciplines, approaches, etc., therefore, will co-exist in the future and will be equal. What would not be equal is artistic value.

Into the future

A new generation of well-trained curators and writers is emerging. Space allows me to mention just two. Susie J. Silbert is the curator of modern and contemporary glass at the Corning Museum of Glass. She feels that her most influential essay on glass was her article on pipes for Glass, “though I think my essay on Norwood Viviano for the Heller Gallery is the most cited (and hardest to find). As for how writers structure their inquiry: I think it really depends on the venue. In my writing for American Art Collector, the articles were short and needed to snap right to the point. I tried to leave the readers with little condensed nuggets of information that perceptively interpreted what the artists were up to; in other words, to say in perhaps 250 words what other writers take 1,500 to say. In this, I looked to Paul Hollister’s very early writings in Collector Editions and the New York Times – he had an interesting way of conveying an artist’s work (and his feelings about it) with minimal text.”

Writing in Glass Quarterly, Silbert expertly categorizes the “emerging” art form of glass pipes:

… it is the highest-end pipes, called “headies” or “head pieces” within the industry, that bear the most consideration as crossover art objects. Recognizable by their sculptural ambition and high-caliber craftsmanship, “headies” so successfully articulate the artistic voices of their makers that they immediately transcend any attempt to categorize them as mere pipes. … While still functional, “imagery is at the forefront of these works,” says veteran mainstream glass artist-cum-pipemaker Robert Mickelsen.27

Kim Harty is a practicing artist and past editor of the Glass Art Society Journal. She sees the community as protesting too much: Rather than dialogue about the work, they dialogue about where the work should be, always with the underlying theme that glass is on its way to being great art rather than judging it on its own merit in the here and now. She tries to address the artwork on its own merit rather than to politicize it, spending less time justifying that it is glass. When I asked her which writers she finds interesting, she asked, “Why is Judith Schaechter’s blog not being published?” and then sent me a few links to emerging writers including Erin O’Connor, Suzanne Peck, David Schuckle, and Mike Hernandez.

The last word

This essay is long, but nonetheless omits many writers and topics. I have not even mentioned the book-length histories of studio glass such as those written by Martha Drexler Lynn, Ferd Hampson, and Koen Vanderstukken. Plowing through the vast written material, I felt at times as if trapped in the situation referenced by my mentor Paul Ricoeur in Symbolism of Evil: “Can we live in all those mythical universes at the same time? Shall we, then, we children of criticism, we men with immense memories, be the Don Juans of the myth? Shall we court them all in turn?” My answer: Absolutely! It is my belief that our field needs to be more collegial, in the sense of more willing to share and act as an interconnected community. We are too often unaware of what our colleagues are doing now and of the history of our discipline, and because of that we fight the same battles over and over again without growing beyond them. I can only hope that this survey will inspire more of us to acknowledge and enjoy the rich history that stands behind what we write today and that gives it legitimacy.

What follows is a list of some of the writers whose work I consulted in preparing this essay. It is by no means complete, but should serve to indicate the richness of the field, and perhaps encourage others to write about the authors I was unable to discuss here:

Glenn Adamson, Sarah Archer, John Asbery, Bill Bagley, Walter Darby Bannard, Annie Buckley, Thomas S. Buechner Sr., Joan Falconer Byrd, Karen Chambers, Garth Clark, Keith Cummings, Arthur Danto, John Drury, Grace Duggan, Gerar Edizel, Barry Friedman, Matthew Gamber, William Ganis, Paul Gardner, Henry Geldzahler, Diane George, Grace Glueck, Clement Greenberg, Henry Halem, Ferd Hampson, Paul Hanna, Kim Harty, Paul Hollister, David Huchthausen, Hamish Jackson, Mark Johnson, Robert Johnston, Victoria Joslin, Robert Kehlmann, Dan Klein, Janet Koplos, Donald Kuspit, Dominick Labino, Helen Lee, Harvey Littleton, Christopher Lone, Martha Drexler Lynn, Pat Malarcher, Ben Marks, Koji Matano, Josiah McElheny, David Mendelson, Robert Morgan, Monica Moses, Linda Norden, Tina Oldknow, Jean-Luc Olivié, Jennifer Opie, Andrew Page, Sylva Petrova, Ada Polak, Richard Posner, Robin Rice, Brent Richards, Helmut Ricke, Alex Rosenberg, Ken Sanders, Elizabeth Sasser, Richard Shiff, Robert Silberman, Susie Silbert, Kim Smith, Penny Smith, Matt Szösz, Davira Taragin, Christine Temin, Linda Tesner, Koen Vanderstukken, Christopher Wall, Wendy Wymer, James Yood

Read more from Issue Two purchase issue

1. Helen Lee, Alex Rosenberg, and Matt Szösz, The Critical Vacuum, Glass Art Society Journal 2015 (Seattle), 23.

2. Mendelson, David, Le verre et les objets de verre dans l’univers imaginaire de Marcel Proust (Toulouse: Librairie José Corti, 1968).

3. The Buechner journal is in the William Warmus archive at the Rakow Library of the Corning Museum of Glass.

4. Glass Art Magazine, Volume II (1974).

5. Glass Art Magazine, (February 1974): 20.

6. Glass Art Magazine, (June 1974): 35.

7. Glass Art Magazine, (June 1974): 34.

8. The Museum Journal,1983 (Lubbock: West Texas Museum Association).

9. The Museum Journal, VI.

10. The Museum Journal, VI.

11. The Museum Journal, 64.

12. The Museum Journal, 68.

13. Art in America, (March 1985): 47 – 53.

14. Glass Art Society Journal, “What Makes Art?” (1982 – 3): 5 – 11 (Shiff p. 7).

15. Glass Art Society Journal, (1982-3): 11.

16. Glass: New Work, 38.

17. Glass: New Work, 23.

18. Glass: New Work, 25.

19. Kuspit, Donald, “Chihuly: Volume 1, 1968 – 1996” (New York: Abrams, 1997), 31; 35.

20. Janet Koplos, “Reconsidering Glass.” Glass Art Society Journal (2006): 43 – 46.

21. Garth Clark, How Envy Killed the Crafts, 445 – 453. PDF file accessed online on September 3, 2017.

22. Walter Darby Bannard “Craft and Art Envy,” Glass: New Work (Autumn 1986). Also delivered as a lecture at the Second Pilchuck Glass Conference in Stanwood, Washington, summer 1985.

23. Unless otherwise noted, quotes from the various writers are excerpted from email correspondence with the author, spring and summer 2017.

24. Marvin Lipofsky: A Glass Odyssey (Oakland: The Oakland Museum of California, 2003), 5.

25. Tina Oldknow, Pilchuck: A Glass School (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996), 122.

26. Monumental Glass for Expo ’67 in Czech Glass Review, 5/1967, 148.

27. Glass Quarterly, (Fall 2014): 48 – 49.