Levi's Denim Art Contest

From American Craft Inquiry: Volume 2, Issue 1

Jeans are a kind of uniform and a category of clothing unto themselves. In a pinch, they offer a face-saving way to punt the bottom half of an ensemble, acting as an always-cool stand-in for something more well thought through. Titans of Silicon Valley regularly turn up in jeans to give talks and make major new product announcements. Jeans are different from pants as a broad category because they mean something distinctive, much in the way that high heels are a category apart from shoes.

We’ve had jeans long enough to be able to recognize their style evolution. Like chairs or cell phones, jeans have their own cavalcade of shifting styles that we can trace decade by decade. Those of us who remember the 1980s can’t escape noticing that form-fitting, high-waisted, acid-washed jeans have reconquered the wardrobes of today’s smart set, and it’s impossible to tell what degree of irony, if any, accompanies their reappearance. But as with most styles, every denim fad that recurs was once brand new. The phenomenon of highly embellished and flamboyantly embroidered “denim art” emerged in the late 1960s, and got its official welcome to the museum world in the ’70s. Nestled among the treasures in the American Craft Council’s archives is a cache of papers and photographs from the Levi’s Denim Art Contest, the Levi’s Denim Art Contest Catalogue of Winners, and “Denim Art,” the resulting exhibition of winning styles that opened at the Museum of Contemporary Craft in March 1974.1

The complex history of jeans makes the Levi’s project all the more compelling, as does the way in which its organizers framed it. Two Rolling Stone colleagues penned a foreword for the catalogue: writer and editor John Burks, and photographer Baron Wolman. “There was a time when Senator Joseph McCarthy and Howdy Doody reigned supreme in America,” they write. “And it was about that time that the Fifties pioneers discovered that on one hand there were mere ‘blue jeans,’ and on the other hand were Levi’s.” Baron and Burks go on to describe the subcultures that came to adopt jeans throughout the ’60s: people who wanted to look like Stokely Carmichael, those seeking the “collegiate look,” the “factory look,” beatniks, and “singles.” Two years before Gloria Vanderbilt’s eponymous line of designer jeans premiered, they describe fashionable women wearing jeans on Fifth Avenue, and they marvel at the ingenuity and verve of the customized jeans and jackets that contestants sent into Levi’s competition.

But Baron and Burks give the 1950s short shrift. However profoundly square the decade’s mainstream popular culture may have been, moviegoers first saw James Dean wearing weathered jeans in 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause, and Elvis Presley performing “Jailhouse Rock” in 1957. Both icons paired their jeans with a black leather jacket and a snarl, to irresistible effect. Suddenly, jeans were practical, durable, sexy, and bad. For uncomfortable pants, this was an impressive feat. How did it happen?

Levi Strauss, a Bavarian immigrant who settled in San Francisco in the 1850s, brought denim to the United States from Europe. In 1873, A Latvian-born Nevada tailor named Jacob W. Davis made a pair of rivet-reinforced pants from denim and found an eager clientele among miners, surveyors, and laborers whose clothing wasn’t sufficiently durable for their work. Davis made a proposal to Levi Strauss & Co., his denim supplier, that they go into business together selling rivet-reinforced clothing, and eventually Strauss made Davis the company’s head of mass production in San Francisco.2 Jeans thus became strongly associated with the West Coast, mining, and lumberjacks.

By the turn of the 20th century, jeans picked up a kind of broad cultural currency in Hollywood movies. The actor William Hart wore jeans in popular silent westerns such as the 1915s Knight of the Trail. American soldiers serving overseas in World War II further popularized denim, and gave denim a new global reach.3 Jeans meant work, but not office work. They were designed to withstand the elements, hold up under harsh conditions, and get softer (and more comfortable) with time. They were the uniform of a particular kind of good guy: American GIs, cowboys, laborers. So if there’s not exactly a straight line connecting California gold miners to the Ramones, or the designers who entered the Levi’s contest, they all eschewed (for different reasons) a certain middle-class, white-collar status quo in their clothing choices. By the time James Dean, Marlon Brando, and Marilyn Monroe made denim part of their respective sartorial images, jeans were mainstream enough to be a known quantity, and a symbol of youth, rebellion, and toughness – even for women.

But why embellishment? One reason is that denim has a practical advantage over other forms of clothing: because it’s designed for hard work, it holds up well to intervention and customization. It’s easy to destroy a T-shirt in the process of trying to customize it with dye, paint, or sewn embellishment; after all, jersey was originally used to make undergarments. Jeans are pretty difficult to ruin, and their appealing and generally flattering blue color offers a rich canvas on which to work.

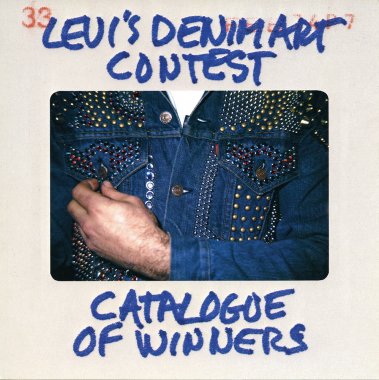

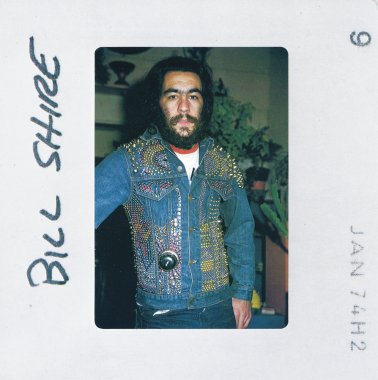

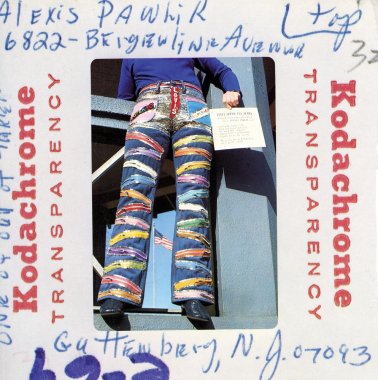

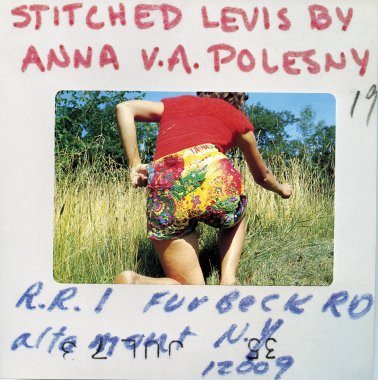

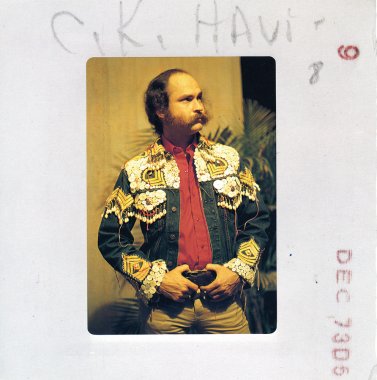

Thanks to its canny PR consultant, Levi’s didn’t miss the boat on this grassroots phenomenon. Held in 1973, the Levi’s Denim Art Contest was the brainchild of Richard M. Owens. His San Francisco public relations firm, Owens & Co., coordinated the call for entries and judging.4 The contest drew more than 2,000 entries from every US state except Alaska, as well as Canada and the Bahamas. The contest’s remarkable panel of judges included photographer Imogen Cunningham; fashion designer Rudi Gernreich; de Young Museum chief curator Lanier Graham; author and designer Alicia Bay Laurel; textile artist Candace Crockett; and Tom Albright, the art critic at the San Francisco Chronicle. The panel reviewed 10,000 slides, and selected 25 winners and 25 honorable mentions. The winner’s creations ran the gamut from delicate and floral to surrealist and psychedelic. The catalogue recreates a sense of the judges’ experience by using enlarged prints of the contest slides to illustrate each winner’s entry. Their names appear on the slides’ cardboard frames along with stamped “MADE IN THE USA” labels, processing dates, and names and notes handwritten in pen.

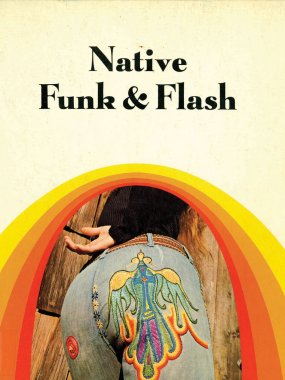

The entries are by and large less 1950s-biker tough and more psychedelically whimsical. Some of the garments were decorated with rainbow-colored metal studs, leather fringe, cotton appliques, sequins, and crewelwork embroidery. Jeans and jackets were cut and resewn into different shapes, sometimes even transforming pants into skirts. The winning entry, Billy Shire’s Welfare, a denim jacket almost entirely covered with metal studs, was simultaneously tough and redolent of high-fashion technique.5 Rivets had historically been practical in the tailoring of denim. Now, studs were being used to decorate its surface. Something had changed in denim’s tone and personality during the late ’60s and early ’70s. The Levi’s contest and exhibition took place the same year as the publication of Alexandra Jacopetti Hart’s book Native Funk and Flash, which captured portraits of makers wearing their creations.6

Before winning the Levi’s contest at age 23, Shire – whose winning jacket was the unanimous choice of the judges – had a business called Ducks Deluxe, making metal-studded leather belts for musicians in Los Angeles.7 Shire’s jacket took him 200 hours to make, and cost about $300 in supplies (nearly one third of his $1,000 prize money). The jacket’s materials, style, and technique touch different corners of the denim universe: physical labor, symbols of the military, whimsy, rebellion, and flamboyant style. He sourced a removable ashtray designed for an antique car for the back of the jacket, and applied a desk bell and a police whistle on a chain to the front. Around the bell, hundreds of red rhinestones radiate outward, as though signaling the bell’s sound waves. Both sleeves are studded in thousands of small rhinestones in blue, green, pink, and gold. Shire applied the stones using a setting machine like those used at Levi’s to attach copper rivets to blue jeans. There are military medals and ribbons, a deep-sea diver’s insignia on the waistband, and a bomber’s insignia on the collar. On the cuffs, he attached emblems of a five-star general. Shire wanted to affix a presidential seal to the jacket – an amusing choice in light of the fact that he was working on the piece during Watergate. His supplier was out of faux presidential seals, so he settled for the insignia of the general chief of staff.

What kind of “welfare” does the jacket reference? There are symbols of military bravery, props of ordinary kinds of work, insignias of government authority, and the visible evidence of hundreds of hours of fastidious work, which – in a sense – acts as the perfect symbol of itself. Jeans have always been made, customized, and worn in places where neckties fear to tread. The impeccable craftsmanship of Shire’s piece is what makes it ultimately jean-like, a counterculture uniform that can be made as individual as any wearer chooses, and in this case allowed the artist to wear his imagination and technical skill on his sleeves.

Read more from the third issue purchase issue

1. Now the Museum of Arts and Design.

2. James B. Salazar, “Fashioning the Historical Body: the Political Economy of Denim,” Social Semiotics, 20, pp. 293–308. June, 2010.

3. “The Complete History of Blue Jeans, From Miners to Marilyn Monroe,” Jennifer Wright, Racked, February 27, 2015.

4. Owens is a co-author, with Peter Beagle, Tony Lane and Baron Wolman, of the book American Denim: A New Folk Art, which was published by Harry N. Abrams in 1975.

5. Billy Shire’s Welfare was displayed in the 2017 exhibition “Counter-Couture,” curated by the Seattle-based designer Michael Cepress. The exhibition opened at the Bellvue Art Museum in Washington state, and traveled to the Museum of Arts and Design.

6. The reference to “Native” in the title of Hart’s book is probably a reference to the borrowing of perceived and real Native American styles and techniques in the making of garments with leather, cloth, beads, and feathers.

7. Levi Strauss & Co., press release announcing the winner of the Denim Art Contest, 1974. American Craft Council Library and Archives, Minneapolis.