Open-Source Activism

From American Craft Inquiry: Volume 1, Issue 1

Banners are powerful. Big, boldly graphic, and visible from a distance, they typically bear a clear and concise message or a call to action.

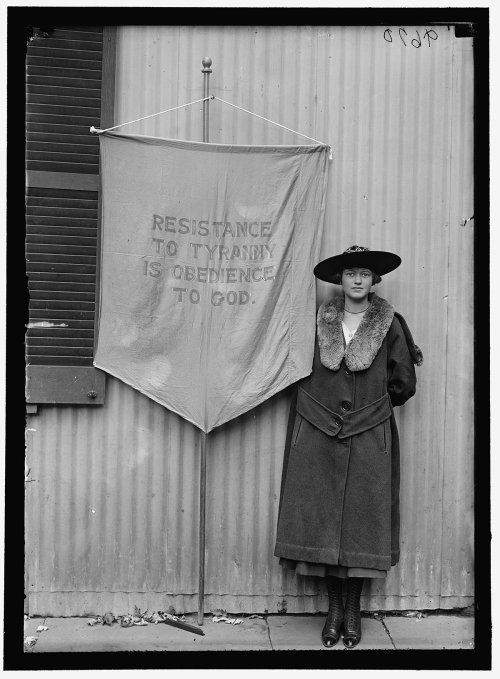

Two social movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, organized labor and women’s suffrage, both emerged just as photography was coming into its own as a documentary form, and banners appear in many images of their marches and protests. They affect the way we see these events in the most literal sense, visually populating scenes of history with their words. Black-and-white images from the turn of the 20th century capture women in fine Edwardian dress and impressive hats, carrying the banners they made to champion the causes of votes for women. In one example from 1917 by the photographers Harris and Ewing in the collection of the Library of Congress, an unidentified young women in a fur collar holds a banner that reads: “RESISTANCE TO TYRANNY IS OBEDIENCE TO GOD.” Another image, circa 1910, shows a group of suffragettes holding umbrellas on which they’ve painted messages entreating observers to join them at a planned march in Washington, DC, “rain or shine.” It’s not difficult to imagine these pared-down expressions as tweets.

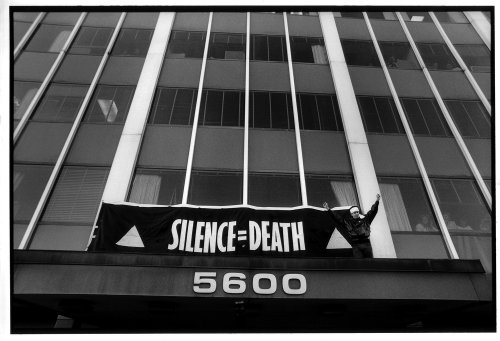

Banners may be handmade and historic, but the digital age has only enhanced their appeal. Contemporary activists have found that social media is a powerful way to amplify their impact. Two-dimensional, straightforward, and compelling, banners just happen to be ideally suited for sharing online. Had Instagram or Twitter existed in 1988, surely we would have found our feeds flooded one day in mid-October by the image of ACT UP co-founder Peter Staley standing triumphantly atop the entrance to the offices of the Food and Drug Administration as a huge banner bearing ACT UP’s rallying cry, “SILENCE = DEATH,” billowed below him. The photograph scarcely needs a caption.

In their very earliest iterations, banners represented the power of the state. Different branches of the military in ancient Rome had their own banners, each of which bore the image of an animal symbolizing their unit: Cavalry legions carried banners decorated with serpents, while the infantry standards bore images of boars, horses, wolves, and, of course, the eagle. In concert with trumpet blasts, standard-bearers would lower, raise, or wave the banners they carried to communicate with soldiers on the battlefield. During the era of the Roman Republic, standards bore the initials SPQR, which stands for Senatus Populusque Romanus, or the Senate and People of Rome, representing not just a particular legion, but the Roman system of government itself.

European heraldry, vestiges of which are still evident in many aspects of daily life in Great Britain and the Commonwealth, such as currency, similarly employs a complex visual code in which elements like stylized griffins, roses, harps, unicorns, and lions symbolize the country’s cultural narrative and history of conquest. The shape of a coat of arms reflects its original function: They were meant to decorate shields, showing an enemy (or, in the worst-case scenario, those who come to collect the bodies) who a soldier is and what he was fighting for. It seems no accident that with a history steeped in the choreography and communication of the battlefield, activists have remade traditional banners into an art form of protest.

So on the morning of November 9, waking up to a new reality in which Donald Trump had defied expectations and won the 2016 presidential election, Berkeley-based artist Stephanie Syjuco looked around her campus of the University of California with the sense that a battle had been waged and lost, but no visual record of the event was visible. In a recent interview with KQED, Syjuco told reporter Sarah Hotchkiss that it had happened so quickly, “there was no visual evidence of the anger and fear and the feelings of resistance.”

So she acted fast in preparation for a rally scheduled for November 10, designing and distributing flyers printed on ordinary office paper bearing the words “Equity, Diversity, Inclusion” – a nod to the university’s Division of Equity and Inclusion. Inspired by visual memories of recent social justice movements like Occupy Wall Street and AIDS activism in the 1980’s and ’90s, Syjuco also became fascinated by suffragist banners as she contemplated what her contribution to this nascent, as-yet unnamed activist movement might be.

“The suffragist banners were amazing because of how ornate they would get,” Syjuco says. “They had tassels and intricate ways to hoist the fabric onto poles. Some of the texts were rather lengthy, as if attempting to present a full argument to a viewer and not just a simple slogan. I thought they were really well crafted and amazing artifacts that held up to physical scrutiny a hundred years later.” Noting the visual contrast with ACT UP’s spare, graphic materials, Syjuco drew inspiration from both movements in creating a new series of banners for the Trump era. And in keeping with her artistic practice, she has made the banners accessible to everyone: Activists located anywhere can download her designs from a Google Drive folder.

Global, Local, and Digital

One of Syjuco’s primary concerns as an artist is the question of authorship. Her, Counterfeit Crochet Project, launched in 2006 and still ongoing, ingeniously explores the global luxury industry by making crochet patterns that mimic luxury logos available to anyone who wants to make a “faux” Fendi baguette bag or Burberry scarf. The concept of “fauxness” itself is thus turned on its head, because the resulting creations are very real for those who made them, and they reify Syjuco’s patterns as well. Like banners, luxury goods sport recognizable signs and symbols, and derive whatever value they have – to producers, advertisers, consumers, and collectors – by dint of their genuineness. But quality aside, the proliferation of fakes proves the point that luxury logos themselves have value, and Syjuco’s witty take on their “realness” underscores this tension.

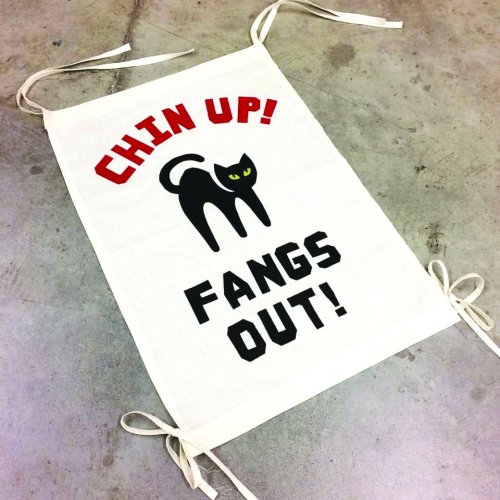

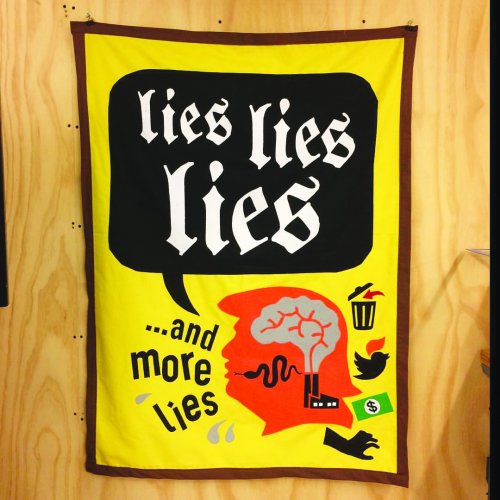

As an artist, it’s less important to Syjuco that her work be attributed to her personally, and more crucial that it be easy to access and share. So she created a how-to document called Making Fabric Protest Banners: Tips + Tricks (available as a PDF file) and 11 different patterns for fabric banners, all of which are rich in color, humor, and calls for unity. One feline-themed design that seems like a cousin of the “pussy hat” phenomenon (which is also open-source) features a stylized black “Halloween Cat” arching its back, accompanied by the phrase “Chin Up! Fangs Out!” Another banner called “Lies, Lies, Lies” makes use of a gothic-style letterform and a silhouette of President Trump’s face rendered (of course) in bright orange. But it was also important to Syjuco not to rely solely on Trump imagery, and she has noticed that the people downloading and making her banners have been attracted to different designs. “Many people have been gravitating toward messages and imagery of strength and love as opposed to imagery of the president himself,” she says, “probably in an attempt to not reiterate or give more of a platform to what they are fighting against. And I think that’s great, since we need to start generating visions of what our future could and will look like in our wildest dreams.”

And what our future could look like is inevitably shaped by our past, for good or for ill. Activists a century ago used banners for their effectiveness, but also because their options were limited. Today, we have digital tools that make sharing information easy – sometimes too easy, as the advent of the “fake news” phenomenon has recently taught us. Working as she does between a relatively low-tech world of fiber and textiles and the more high-tech realms of digital artmaking, Syjuco says she likes the connection between the two. “I’ve moved fluidly in this type of manner for a number of years,” Syjuco tells American Craft Inquiry, “and it’s partly to try to collapse the distinction between what can appear to be separate modes of making (old vs. new, digital vs. analog, etc.). Each arena has its strengths and when you combine the two you can get unexpected resonances.”

And she’s not alone: the Chicago-based artist Aram Han Sifuentes has created the Protest Banner Lending Library, which works in a similar way to Syjuco’s Google Drive banner resource. The Protest Banner project includes a real space, reminiscent of Sabrina Gschwandtner’s 2007 Wartime Knitting Circle, in which people can learn sewing and fiber techniques from one another as they create banners, fostering a connection in the real world between activists and makers. Thanks to the efforts of Syjuco and Sifuentes, records of this moment in history will exist in multiple places. They’ve already been captured in photographs of the marches and protests, they will live on in the form of the banners themselves as historic artifacts, and they will live, perhaps forever, in a new, third space the suffragists never could have imagined: the digital network that now connects us with shared imagery and symbols for resistance. They are the modern-day shields that remind everyone who we are, and what we’re fighting for.

Read more from the first issue purchase issue