Rugged Individualist

Rachelle LeBlanc's obsession revitalizes an old technique.

One Saturday morning at home in Montreal, Rachelle LeBlanc got her two young daughters up and fed, then announced to her husband she was taking the rest of the weekend off. She needed the break. Her career as a sportswear designer was demanding; any tiny error in her work might cause a major customer such as Walmart to cancel a huge order. Burnout loomed. “It’s very stressful when your life depends on the size of a button or a thread color,” she says.

LeBlanc drove south across the border and wound up at the Shelburne Museum in Vermont. There, among the museum’s renowned troves of Americana, LeBlanc was instantly smitten by the rug collection. “They were all hand-hooked or punched, made in the older style,” she says. “I was very curious about how they made them.” One of the rugs that caught her attention was based on an Impressionist painting. LeBlanc painted as a hobby, and she wondered whether she could recreate some of her works as rugs.

Back at home, with fabric samples from work, snippets of her daughters’ old baby clothes, and a latch hook provided by her mother-in-law, LeBlanc made her first rug. That was in 2003, and she hasn’t stopped since.

“Every so often, you stumble across something that piques your curiosity,” she says. “I became completely obsessed.”

That obsession led her to a flourishing career. These days, the artist, 48, hooks rugs and three-dimensional sculptures that end up in museums and private collections. She’s shown work in numerous solo and group exhibitions across the United States and Canada, and her pioneering exploration of the medium has attracted recognition that includes a prestigious Canada Council for the Arts grant.

From the beginning, LeBlanc saw rug hooking as an art form. When her family moved to Alberta in 2008 in search of a slower pace, she tried joining a rug-hooking hobby group, but it wasn’t a good fit. “Everybody was focused on buying patterns. I felt like a fish out of water,” she says. “For me it was all about art. It wasn’t about having something on my floor, or showing in country fairs. I wanted my stuff to be in art galleries.”

LeBlanc has always gone her own way. A citizen of both the US and Canada, she grew up spending hours in her parents’ fabric store in the small fishing town of Bouctouche, New Brunswick. She learned to sew early on and made a lot of her own clothes. “I used to get laughed at for some of the things I made,” she says, recalling certain Cyndi Lauper-inspired looks. “But it was an interesting childhood. I had a fierce independence. I didn’t want to look like everybody else.”

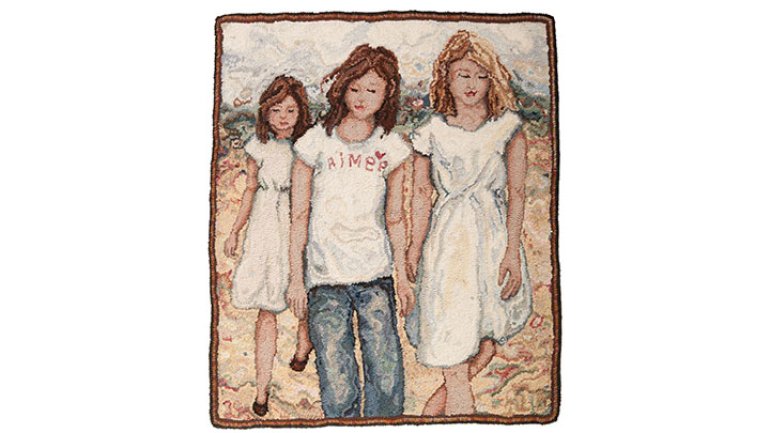

Her work’s imagery often springs from her own memories. Landscapes and children are frequent themes, and her painter’s eye is apparent in her renditions of flowing textiles and undulating terrains. Working from snapshots or staged photos, LeBlanc starts each design with a version painted in watercolor to establish a palette.

Once she is happy with the plan, she dyes fabric, then cuts it into strips of varying widths with a pair of scissors she’s had since her garment industry days. Some rug hookers use a cutting tool that creates many strips at once, but LeBlanc snips them one by one, which she prefers “because it’s imperfect.” With strips that vary in width from thread-size to a quarter-inch, she is able to create variations in texture that enliven her works. Hand-cutting also allows her to shape strips to a particular purpose; those destined to become a head of hair, for instance, can be tapered at the ends.

It’s a slow art – she might spend a month on a 36- by 44-inch piece – but LeBlanc finds it peaceful. “It’s very rhythmic. Everything else that’s going on kind of falls away,” she says.

Each rug is finished with binding hand-woven by a Manitoba artist to represent the traditional sashes of the Métis, Canadians who descended from both European settlers and First Nations peoples. “I wanted something that said Canada,” she says. The binding also represents LeBlanc’s devotion to craftsmanship. “Unless you look at the back of the piece, you’d never notice it.…What I make is not mass production. There’s thought that happens with every single loop.”

LeBlanc’s recent 3D sculptures, which evolved from her experiments in making hooked baskets and vessels, have brought rug hooking into a whole new realm. The sculptures were envisioned to fill a gallery where her rugs would hang on the walls. “I thought, ‘Maybe if I take the children from my rugs, I can create them for the middle of the space.’ ” The first sculpture was of a 1-year-old boy.

Expertise in patternmaking, honed as a fashion design major at Sheridan College in Ontario and in her design career, served LeBlanc well in figuring out how to make rugs in the round. “It’s vital that no seam allowances be visible, so when you look at a piece you cannot tell where it’s stitched closed,” she says. “To hide that, you have to hook through the seam allowances. I want you to look at it and say, ‘How did she do that?’ ”

The accolades LeBlanc’s work has received spur her to keep asking, “How do I measure up?” She finds her answer at work in her home studio, one loop at a time.

“For me, there is no ‘no’,” she says. “Anything is possible.”