Sonya Clark at the Fabric Workshop and Museum

When Sonya Clark and the team at the Philadelphia’s Fabric Workshop and Museum were putting the final touches on the installation of her exhibition “Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know,” it became clear that the gallery space – which houses an array of works made from subdued white textiles – needed a bit of vivid color. A solution was at hand: The museum’s exhibitions manager Alec Unkovic went to the local Benjamin Moore with a sample of the deep-madder red threads that run along the edges of the Confederate Flag of Truce (in fact, a repurposed dish towel) that inspired Clark’s project.

He found the perfect match, but the paint chip had a chilling surprise in store. From the paint store, he texted “you are not going to believe this."

The matching color chip was labelled '”Confederate Red,” says Clark, adding that Benjamin Moore even described the color as “a timeless and enduring classic" on its promotional materials. “They later rebranded the color 'Patriot Red,' which only serves to legitimize the way in which people hold onto Confederate ideals as though they're patriotic,” says Clark. The team painted the exhibition’s title wall with the color, identifying it just as the paint chip was labeled: Benjamin Moore Paint Color 2080-20 Confederate Red. Clark’s installation at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, itself a former flag factory, is full of just these sorts of visual and conceptual twists, in which something that might appear at first to be quite ordinary turns out to be fraught with massive social and historical consequences.

Visitors to this exhibition might remember Clark’s 2017 performance Unraveling at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts just a few blocks away, in which she invited members of the public to deconstruct a Confederate battle flag thread by thread. It’s delicate work, more complex and trickier than most people expect. The Confederate battle flag, with its design of a blue “X” and white stars on a red ground, is immediately recognizable.

The original truce flag is in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC. Clark discovered by chance while she was an artist research fellow at the Smithsonian. Its NMAH website description says “towel was used as a flag of truce by Confederate troops during Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865.” It was acquired by the Smithsonian in 1936 at the bequest of Elizabeth B. Custer (1842 – 1933) the widow of General George Armstrong Custer, who was present at Appomattox. The flag is yellowed with age, but otherwise in good condition. It looks humble, like the household object it once was. As Civil War objects go, the towel is almost unparalleled in history for sheer significance: it served – for lack of a suitable alternative – as the symbolic seal on the truce that ended the war. Yet it’s probably one of the least known artifacts of the period, and, as Sonya Clark illustrates in this exhibition, that’s not an accident.

On their surfaces, the Confederate battle flag and the Confederate Flag of Truce could not be more different. Where the battle flag is vivid and bold, the truce flag is subtle and almost modernist. The battle flag, by contrast, is eye-catching: "Flags are designed to be visually striking, because they needed to be visible on the battlefield. But the reason we know the Confederate battle flag and not the Flag of Truce isn't a question of graphic design, but of propaganda,” Clark says. “The KKK and other white supremacist groups adopted this particular Confederate flag, of many, in their ongoing campaigns of terror. People, especially those not from the South, will sometimes say, ‘I never saw the Confederate flag around when I was growing up.’ But you know what it looks like, which means that you did see it, maybe even as it slipped into popular culture and that means the propaganda had its effect."

One of the works in the exhibition, entitled Propaganda, is comprised of a list of hundreds of objects that you can buy emblazoned with the battle flag. Umbrellas, wristwatches, sweatshirts, salt and pepper shakers, and – bizarrely – yoga mats. The ordinariness of the things on this list, many of which can be worn or displayed, speaks to the way in which the flag and its meaning have been normalized.

The Flag of Truce, by contrast, suggests women’s

There are interactive works in the exhibition including looms lent by local universities for a piece called Reconstruction Exercise, where visitors can see how it feels to weave and watch the cloth take shape. In a piece called Lesson Plan, there are also old-school desks fitted with a textured panel that allow visitors to make rubbings of the flag, and get to know its texture first-hand. Clark worked with the team at the Fabric Workshop and Museum to create a massive version of the truce flag called Monumental that spans 30 by 15 feet. Its companion piece, Many, comprises 100 small flags the size of the original, arranged in neat rows like a quilt-in-progress, on a huge platform.

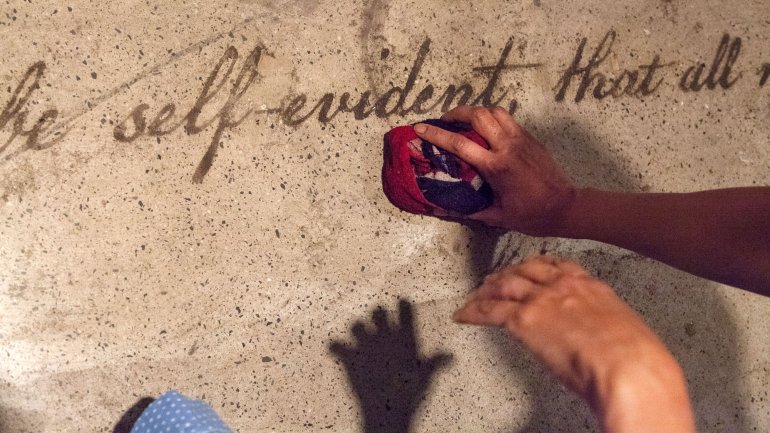

On March 30, Clark gave a public performance of a piece called Reversals, in which she used a dish towel printed with the Confederate battle flag to clean the gallery floor. In the piece, Clark was dressed to resemble Ella Watson, who was made famous in Gordon Parks’s photograph American Gothic in 1942. Dust from outside Independence Hall was collected and sifted onto the gallery floor by FWM staff. As Clark wiped it away, the preamble to the Declaration of Independence was revealed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” “Self-evident,” perhaps, but in this case, only because they’ve been made visible in real time through hard work.

Clark’s project at FWM asks what “monumental” truly means. Our word monument is derived from a Latin word, monere, which means “to remind.”

And the truce flag, which represents a pivotal moment in American history but is not an iconic object, is a perfect vessel for the formation of new memories in the form of a thought experiment. Clark asks: What if this was the flag we all recognized? What if there was a truce flag in every classroom in America? What if there were truce flag bumper stickers, or you could buy truce stamps at the post office? What if it appeared, like a minimalist talisman, everywhere Americans come into contact with the federal government? It’s not impossible. Clark reflects on how much has changed in 100 years and how much we still have to do.

"Life liberty and the pursuit of happiness, but for whom?,” asks Clark. “People will say ‘things are better now.’ And in a way it's true: I’m a college professor at one of the best liberal arts schools in the United States. That would not have happened 150 years ago. But we’re also incarcerating and killing black and brown people at alarming rates, and there are concentration camps at the US-Mexico border. Things are better, yes, but simultaneously worse. All in all, we are very far from where we need to be.”

Weaving is difficult, laborious, repetitive, prone to mistakes, and it takes a long time. If the truce flag symbolizes a conscious retreat from systematic racism, then the labor of making replicas of the flag and weaving each thread to make the pattern is as apt a metaphor as any for how long and far we still have to go.