Masters: Gerhardt Knodel

Masters: Gerhardt Knodel

When you come upon Gerhardt Knodel, cutting scallop shapes out of thick fabric in his cavernous studio near Detroit, he is alone – and supremely happy.

“Every day it’s a pleasure to come to the studio, to open the door, to get back to work,” he says. Many days he doesn’t even turn on the radio; he doesn’t want the distraction. “The life is here,” he says. “This is fabulous.”

Seeing him absorbed in his latest body of work, which draws inspiration from a centuries-old scrap of patterned cloth, you might decide that Knodel, one of the most accomplished fiber artists of our time, is especially self-reliant and self-possessed. You might think, “Here’s a guy who’s thrilled to be retired from Cranbrook Academy of Art,” where he was director for 12 of the 37 years he worked there.

But Knodel is not some solitary virtuoso shutting out the world. His fulfillment – as an artist, as a teacher – has always come through connection with other people. Neither star nor recluse, at his core he’s an ensemble player. As a teenager, he relished working with his art teachers to decorate the gym for dances and the auditorium for theater productions, discovering the power of textiles to transform a space for a crowd. As a young high school teacher, he loved interacting with kids. “Bam! That was it,” he remembers. “It was so exciting to have 150 students coming into my room every day.”

What he recalls most fondly of a six-week weaving workshop at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in 1967 were the deep bonds that formed between the students as they worked, passionately, around the clock. Before they parted, they sat in a big circle, sipping wine and reflecting. Fifty years later, he still savors “the pleasure of being part of a communal experience of making,” the memory of being in that intense creative circle.

Of course, other people are complicated; they don’t always offer cozy fellowship. Sometimes they challenge your perspective – which Knodel also values. He recalls, as a UCLA undergrad and a classically trained potter, watching students of Peter Voulkos manhandle lumps of clay at the wheel in Berkeley – and feeling baffled and amazed. “That was really the first time that I had felt such a major contradiction to something that I had learned,” he says. He returned to UCLA convinced something was missing in his education.

When he settled in at Cranbrook in his 30s, he treasured the honest camaraderie, the give-and-take with other faculty leaders, who are artists in residence. They would come together, show their work, he recalls, “and engage in criticism very openly, with a kind of trusting relationship that was based on respect for the differences among us.” He relied on that feedback and grew because of it.

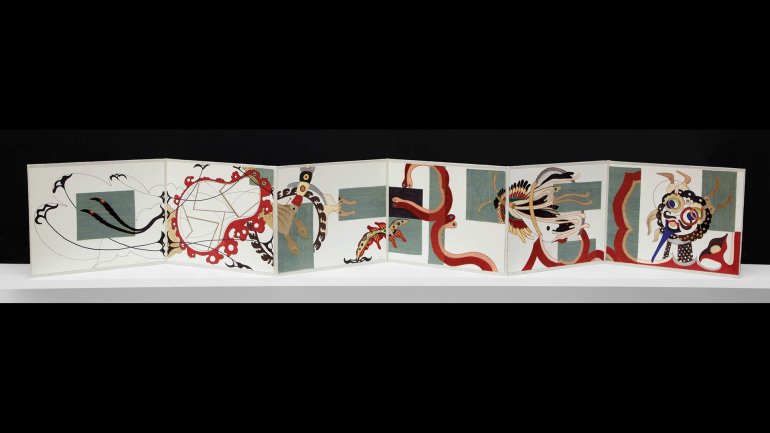

Today, though he is working by himself, in a sense he still feels part of a community. Tapping into his vast store of historical textiles, he’s using them as reference points for his own ever-evolving work. As he cuts a piece of mass-produced fabric and arranges it in an assemblage, he’s thinking about the people who’ve gone before. “It’s so interesting that historically, a good part of the world’s population was invested in textile-making,” he says. “It was the preoccupation of 90 percent of human beings.” Here, in his studio, surrounded by “bits and pieces of attention of people from other times and places,” Knodel is hardly alone. And he enjoys the company.

Suspicion No. 1: “I am really suspicious about so many young artists outsourcing their work. I talk to graduate students in many parts of the country who simply will say: ‘No, I didn’t make it. I designed this piece of sculpture and I farmed it out to someone else.’ We’re getting to the point where we don’t even ask the question about the making.”

Suspicion No. 2: “I’m very suspicious about artists who establish a look to their work and then become slaves to their success. And the work becomes only repetitive. … Living in this very exciting world of change that we’re in, how can one drag along one’s past to the degree that so many people do?”

The limits of intention: “We all live with our fingers crossed as we make things. We all hope that our ideas are leading in the right direction. But the interesting thing in art is that it’s a by-product of intention. One doesn’t intend to make great art.”

You reap, you sow: “The degree to which one commits, as a dancer or a musician or a craftsman, to learn the basics is the degree to which one creates a platform for ultimately discovering art.”

Read more about the 2016 American Craft Council Awards and winners.