Piecework

Piecework

From his beginnings as an artist, Jim Rose has stayed open to influence. The result is furniture that stands apart.

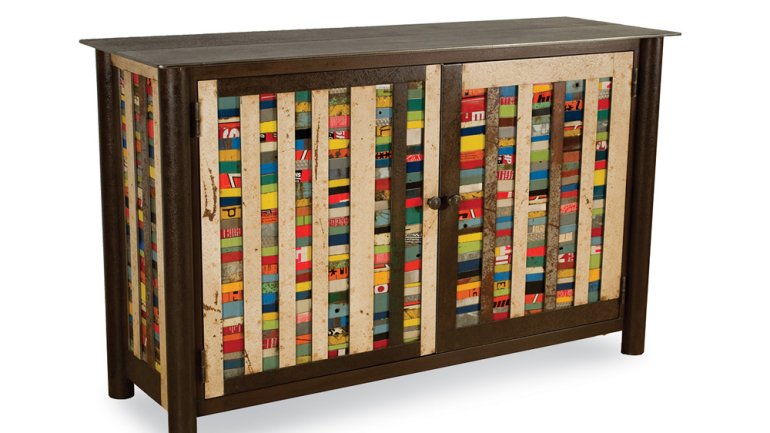

What registers first when you look at Jim Rose’s furniture? Maybe it’s the clean lines of his Shaker-inspired designs, or the bursts of blocky color in the quilt-like panels that brighten drawer fronts and doors. Maybe it’s the unexpected material: not wood, but reclaimed steel, soothed with wax finishes. Maybe it’s the meticulous craftsmanship, honed skill, and clear vision manifest in his finished forms.

Whatever hits first, the magic is almost certainly in how it all comes together.

For 17 years, Rose has been crafting furniture in Door County, Wisconsin, where he lives with his wife, their 10-year-old daughter, Delilah, and a Jack Russell named Daisy. He works in an old creamery, a 100-year-old Belgian-brick structure converted into 2,250 square feet of workspace. A green mechanical shear dominates the shop floor, as colorful pieces of aging steel rest against the walls.

The setup suits the thoughtful, grounded artist. Yet Rose’s road to this place – and his perceptive approach to making – began far outside of Wisconsin. Born in Indiana, Rose grew up in Europe. His father’s employer, a pharmaceutical company, brought the family first to France, then England. “My parents were always taking us on trips to see museums, different cultural sites,” he recalls.

Rose returned to the United States in the 1980s, studying photography at Bard College for two years before transferring to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He was hungry for a broad-based art education, but also eager to work more directly with his hands. As a student of sculpture, he began making jewelry and casting bronze, combining wood and metal. He also met his future wife, Suzanne, another SAIC student who is now a fine art photographer.

It was 1989, his last year at SAIC, when Rose walked up to Chicago gallerist Ann Nathan with a Polaroid photo of a jewelry stand he’d made – one of his earliest pieces of furniture. A huge fire had recently laid claim to her gallery, Objects, along with eight others in the same building. The exiled art dealers had set up temporary shop at the city’s Merchandise Mart. Even amid tumult, Nathan was struck by what she saw.

“It was fresh work,” says Nathan, whose Ann Nathan Gallery today specializes in paintings, sculpture, and studio furniture. “I can’t explain it. I never know why or how I do a lot of these things, but it was very fresh – and I took a shot.”

After some good shows and commissions in the early ’90s, Rose and his wife relocated to Wisconsin, purchasing their property in Door County in the spring of 1994. Not long after, a road trip to the East Coast sparked the distinctive furniture for which Rose is now known. Just as his parents would have, Rose and his wife stopped at a couple of cultural sites – Shaker museums and settlements in New York and Massachusetts. “Seeing their whole life, and that all of it was made by hand, was just so inspiring.” Craftsmanship, quality of materials, integrity of design – the combination was captivating. “That was when I really took off making furniture.”

Rose began researching (“I’ve since acquired so many books”) and building his interpretations in steel: tables, cupboards, clocks. At the time, he was buying metal at the scrapyard because that’s what he could afford; reuse has since evolved into an environmental ethic that permeates his practice, from the steel to the nontoxic, natural wax finishes. He had brought in three Shaker-inspired pieces to Nathan, he remembers, when she asked him how many more he could make; she was giving him his first solo show.

Rose spent the next seven years exploring his Shaker interpretations in depth, producing some 250 one-of-a-kind works.

In 2003, inspiration struck again, this time at an exhibition of Gee’s Bend quilts at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Rose recognized a congruity between worn fabric and weathered steel, between quilts constructed out of recycled textiles and his own practice of reclaiming scrap metal. “It was like, wow, that just really, really translates well.”

While his early Shaker interpretations were mostly monochromatic, color defines his quilted works. Strips of canary yellow, blocks of rust-speckled orange: All of the color and patina is natural. If his heart is fixed on a particular color or traditional quilt pattern – drunkard’s path, maybe, or flying geese – “I’m at the mercy of what I find at the scrapyards,” Rose says.

The scrapyards, scattered across the Midwest, have been generous.

Rose begins by constructing a piece’s frame, laying out panels and welding them up (“like making a stretcher for a painting”). Then the fun begins. He stands over a table, arranging and rearranging countless pieces of cut colored steel. Everything is fastidiously tack-welded, before wire brushing and wax finishing. He has up to six pieces in progress at any time; one longtime assistant helps. He completes about four pieces each month.

At a time when reclaimed materials are chic, Rose “has taken that kind of piece to a new and high level,” says Nathan, whose gallery continues to represent the artist. “If you open the doors or the drawers, they’re just as meticulous on the inside as they are on the outside.”

Over the years, his pieces have become more colorful, his patterns more complex. Lately, Rose says, he has been picking up pieces of metal with words on them at the scrapyard, incorporating text into his work. He’s also been looking at work by collage and outsider artists, thinking about how he might bring even more elements together.

He won’t speculate on where that might take him. “I’m looking for what I can do next, but at the same time I have to be open to being inspired,” he says.

“It’s a step-by-step process. You complete one thing and move on to the next, and hope that you’re being inspired – or that you’re going to see something that inspires you to make the next thing.”

Julie K. Hanus is American Craft’s senior editor.