Studio on the Street

Studio on the Street

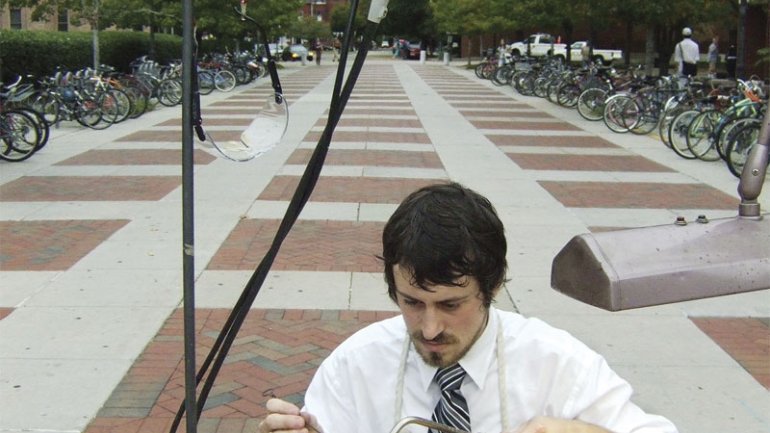

Jeweler Gabriel Craig discovers a new way to share his work.

In 2007, on a cold October afternoon in Richmond, Virginia, I gathered my tools, wheeled my bench outside and began The Collegiate Jeweler, a series of performances. “Making jewelry by hand is like magic,” I said to a gathered crowd. “In an age when people are disconnected from the means of production, they have no idea how things are actually made. So when they see something they don’t understand, something that seems impossible for them to do, it’s magical.” For many standing around that day, jewelry suddenly became a lot more interesting.

Over the next month I took to the streets, making my work and using my bench as a soapbox to preach the jewelry gospel. My objective was simply to share handmade jewelry with those who may not ordinarily encounter it. I wanted the format of the performances to reflect my educational and altruistic goals and so I gave away silver rings that I made on the spot—over 30 in the first few weeks. By giving away jewelry I was able to focus on its cultural value rather than its commercial value. The criterion for receiving a ring was participation. Those who seemed interested got to take home some of the excitement.

I was spurred on by the attention and spectacle that public performance creates. I sought to engage an audience by being provocative, but to keep them interested with entertainment, education and, of course, the promise of getting something valuable for free. On Halloween I procured some flash paper (material that burns brightly and quickly disappears), and after heating my metal, I used it to ignite the paper and then pointedly tossed it in the air. The gathered crowd jumped and screamed with delight. In the studio I am just a jeweler, but on the street I am a magician.

Combining jewelry with performance transcended medium and process to become a cultural experience. I knew immediately the impact of this type of practice. I could see it in the eyes of my audience. I wasn’t sure what kind of change I could effect by bringing my studio to “the people,” but I knew that there was more to making than just producing an object that would seduce and sell. Approaching jewelry as a theme, I found that the opportunity for communication and change grew exponentially. Despite how pervasive jewelry is in our culture, as a maker I spend a lot of time in the studio by myself, complacent in the isolation and insular world built around studio jewelry. With The Collegiate Jeweler performances, I had finally found a direct way to share what I do with people. That was how it started—wanting to share and be inclusive. Being an exhibitionist didn’t hurt either.

By taking my studio practice outside, I was afforded a direct interaction with my viewers, many of whom may never enter a gallery, museum or craft fair. I wanted to emphasize the personal relationship that we all have with jewelry, and so the accessibility of the handmade became a frequent topic of conversation. Before giving away the rings, I would strategically ask people to reflect on the experience of watching me make them and the conversations we had, essentially turning simple silver rings into vehicles for memory. At my suggestion, the rings came to contain the experience; they stood as a symbol of the value of the handmade in our culture, and of the accessibility (and inaccessibility) of art. The recipients of the rings left the performances with a tangible reminder to be good jewelry viewers.

I soon realized that I was not alone in wanting to share my craft directly. Multimedia artist Michael Swaine has been taking his sewing machine to the streets of San Francisco in his Free Mending Library project since 2002. And since 2006, Frau Fiber (Carole Lung) has been organizing fiber-based outreach events, such as Sewing Rebellion, which promote garment construction skills. Something was definitely in the air.

Encouraged, I began The Pro Bono Jeweler performances in 2008 with the slogan “If lawyers, why not jewelers?” I stressed the dichotomy between jewelry as a signifier of status and jewelry as universal form of personal expression. With this in mind, I teamed with Quirk Gallery in Richmond, Virginia, who hosted me in conjunction with their openings. Quirk was a logical choice because of their vested interest in the accessibility of jewelry. In November 2008 they presented a Robert Ebendorf exhibition in which the acclaimed jeweler sold 200 pendants for just $50 each. In Quirk, I found an institutional ally. “It was entertaining for both our patrons and for passersby,” says Katie Ukrop, owner of the gallery. “For each person to have a piece of jewelry that they saw being created—or created themselves—acts as a constant reminder of the process and the artist, and anything that creates enthusiasm about jewelry is something we want to promote.”

The first Pro Bono Jeweler performance took a similar form and had comparable goals to those of Collegiate Jeweler. It highlighted, however, that even in proximity to a gallery, most people aren’t familiar with how jewelry is made or its cultural implications. In the most recent incarnation of Pro Bono Jeweler, I changed tack and invited the audience to participate. “Would you like to make a piece of archeologically inspired jewelry?” I asked. Providing polymer clay and synthetic gemstones, I asked people to leaf through historical jewelry books for inspiration and to interpret a design. By encouraging participants to become aware of historical works and familiar with handwork, I was able to instill in them a greater appreciation of jewelry. Over 40 people of all ages from diverse backgrounds took part. Some people came for the art opening, others were just waiting for the bus; but in sharing the history and making of jewelry, all were equal.

Over the past two years, watching people discover jewelry for the first time has reminded me how exciting it was to first discover the process of making something. The audience’s unwavering enthusiasm keeps me going back to the street. For now, the performances are ongoing, with the format ever evolving though the goal will always be the same. As a self-appointed studio jewelry ambassador to the public-at-large, I want to do for jewelry what Bill Cosby did for Jell-O—make it fun and appealing. Yet, finding and reaching a wider audience is not so easy. When I talked to Lydia Matthews, a New York-based cultural critic, last year, she confided that she regards universal appeal as a modern myth, and I’m inclined to agree. “The ‘wider audience’ is just a bunch of subcultures and small collections of people brought together by a theme.” This is where I am today, finding diverse subcultures and venues that will let me institute my guerrilla jewelry indoctrination. I want to take my studio practice to where it can make a difference—outside the studio.