Whirlwind

Whirlwind

Three and a half years ago, Audrey Rosulek’s husband gave her a gift certificate for a pottery class at the Clay Studio of Missoula. Their son was an energetic preschooler at the time, and Rosulek jokes that she would have rather had sleep. “But it was a gift, right? So I went.”

The next segment of her story might surprise anyone who’s had the pleasure of handling one of her beautifully executed porcelain pieces – or taken note of her swiftly ascending career. Rosulek doesn’t describe a magic connection to clay. No flash of brilliance in her first turn at the wheel. “At first it was really awkward; that’s just how it is,” she says. “At the end of the class, I wouldn’t say I had that much to show for it. But I walked away with the idea that I wanted to keep doing this.”

She continued taking classes. As her comfort with clay grew, she set her sights on a short-term residency, knowing she would need a portfolio and résumé to apply. “I went into it with the attitude of, OK, this could take years,” she says. In 2010, she applied to her first juried exhibition, Barrett Clay Works’ National Cup Show in Poughkeepsie, New York. She got in. Then she got a phone call: She had won best in show.

“It was crazy,” Rosulek says. But it was also a confidence booster. “I started to think, OK, maybe I’m onto something here.”

The Montana native credits her home state for providing an abundance of resources to ceramists. The Clay Studio, just a short drive from her hometown of Lolo, draws a rotating cast of talented resident artists. (In 2011, she became one herself with a short-term stay.) So while Rosulek didn’t study ceramics in college – her BFA is in painting and drawing – she’s been able to learn from many who did. “I always joke that I got a hand-me-down education,” she says.

A workshop at Helena’s Archie Bray Foundation, for example, put her on the path to the cool curved handles that define her latest work. Instructor Jeff Oestreich had asked participants to bring slides for a critique. “He was really excited about some of my surface things,” Rosulek recalls. “But he said, ‘Your handles – they’re really dumb.’ ” She laughs at the memory, explaining how she had been cutting them from slabs. “I was like: They are dumb. I never saw it before.”

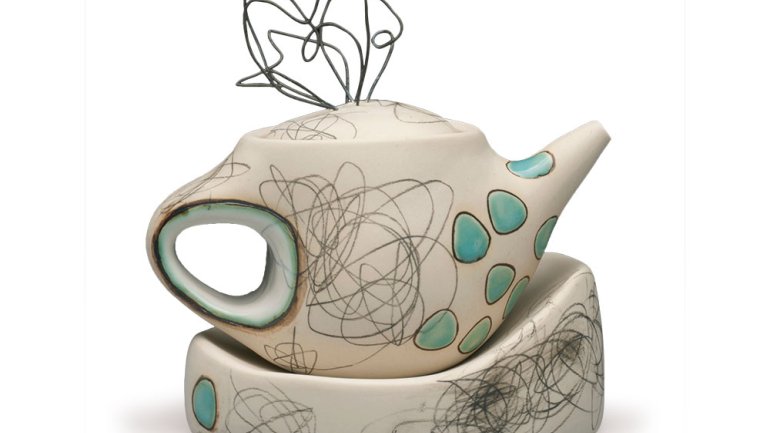

Oestreich, who had apprenticed with Bernard Leach, showed her the famed potter’s technique for pulling handles. She experimented for a year with different styles before finding her sweet spot. Today she pulls a handle, cuts away from it, then adds clay around the attachment points, creating a soft, organic loop that invites cradling fingers. She often glazes only the inside. “I like the thought of glazing the area where the pot is held, so that part has some protection.”

She steps away from glaze a little bit more, she says, with every load of work she puts in the kiln. “I like the raw clay surface; there’s just something so exposed about it.” It’s also an ideal canvas for making marks. Underglaze pencil in hand, Rosulek finishes her pots with scribbles and sketches inspired by Montana’s wide-open landscape and fiercely cycling seasons. The result is refined and spontaneous, elegant and wild.

More than a few people have noticed. In April, Rosulek was named a Ceramics Monthly emerging artist. As 2012 drew to a close, exhibitions crowded her calendar – at Charlie Cummings Gallery, Baltimore Clayworks, and Crimson Laurel Gallery (where she is March's featured artist), among others. Her work also appears in the 2013 NCECA Biennial at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft.

Rosulek is enthusiastic, but also humbled by the attention. She just started another residency – this one long-term – at the Clay Studio, and is looking forward to the spring as a time to dig in again, try some new ideas. “Until then, I’m just day by day.”

Julie K. Hanus is American Craft’s senior editor.