[Object As...] Alex Anderson

[Object As...] Alex Anderson

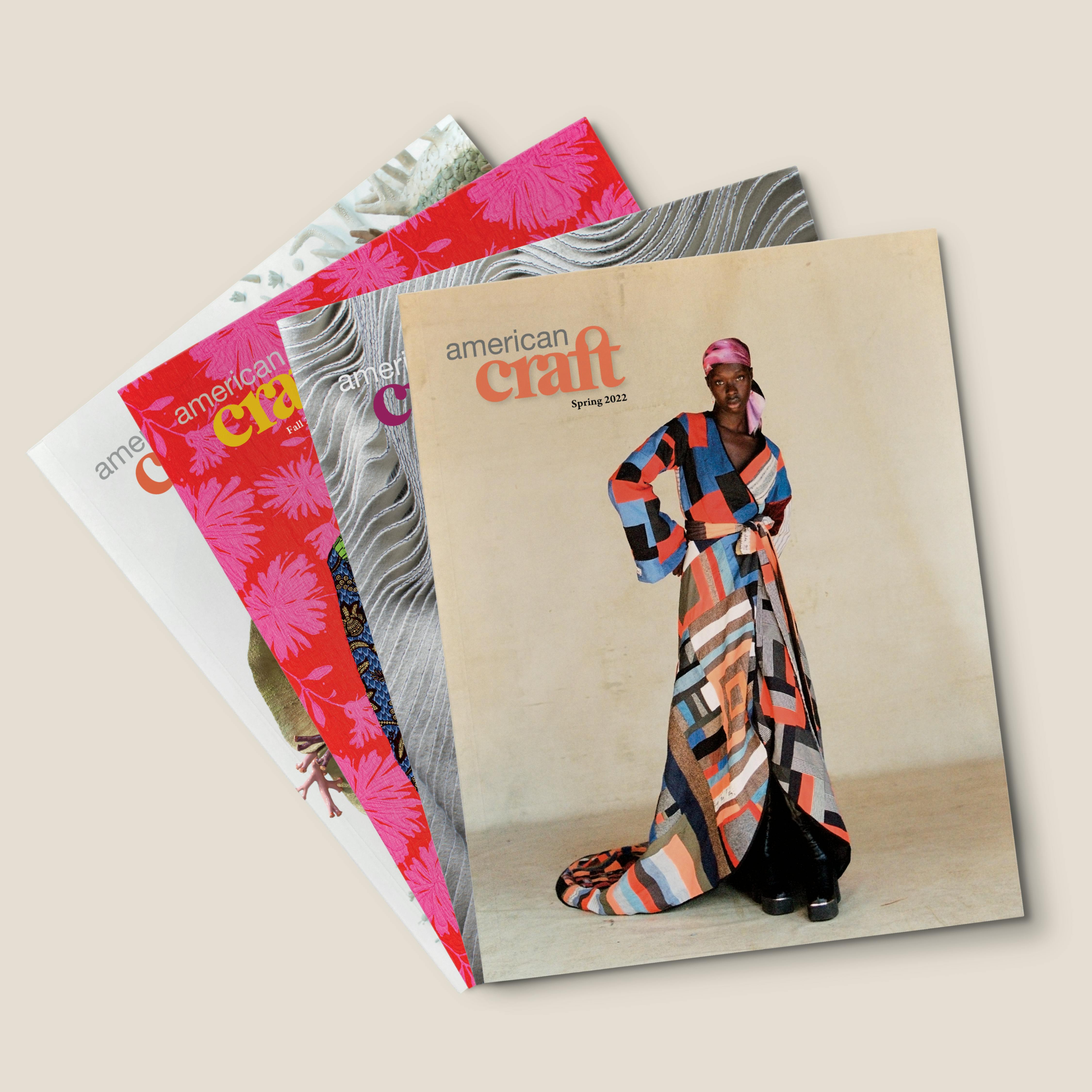

Alex Anderson, Burn It All Away. Photo courtesy of Gavlak Gallery.

About "OBJECT AS..."

Objects fashioned by craft artists can do more than appeal to the eye and hand. They can speak to our cultural, political, environmental, and social climates. They can comment on today’s issues and inspire conversations. They can be acts of rebellion.

That’s the point of the “Object As . . .” project, for which six artists were chosen by six curators selected by the American Craft Council. Supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the artists created works that speak—subtly, directly, intimately, publicly—about issues that matter to them. The works testify to the diversity of makers and practices and to the ongoing impact of craft on our lives. Read more about the project.

Below you can listen to an American Craft Podcast interview with one of the participating artists and read their story about how their object came into being and what it means to them, followed by a note from the curator.

Burn It All Away | Alex Anderson

Burn It All Away depicts an idyllic nature scene catching fire under the rays of a burning sun while an anthropomorphized gazing pool smiles in witness to this circumstance. Wet footprints step away from the pool, suggesting the departure of the reflected subject, or perhaps of the reflection itself. The burning flowers in this scene are daffodils, which are of the genus Narcissus, connecting the classical myth with its floral symbolic stand-in and the reflecting pool central to the familiar narrative of self-obsession. In this image, the light of the sun represents personal enlightenment, self-awareness, and knowledge, key to the transcendence of a fixation on the self and one’s physical and imagined image.

As the light intensifies, the flowers burn, signifying the way in which a greater understanding of reality and the larger harm narcissism causes to the self and others can be a catalyst for informed healing and change. The pool smiles because the physical body it was reflecting is free of the pain and confines of a disorder people often think of as an unabated self-love at the expense of those who interact with the narcissist, when in fact the narcissist lives in a state of unseen suffering. The maladaptive self-obsession is a form of both compensation and protection that, in this image, the person reflected no longer needs, so nothing feels better than burning it all away.

Alex Anderson received an MFA in Ceramics from UCLA after earning a Fulbright grant in affiliation with the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou in 2015. His recent work explores Black and Asian American identity through the lens of millennial culture.

Curator Notes on Burn It All Away | Suzanne Isken

Let’s start with the facts. Alex Anderson was born in 1990. He is of Black and Japanese descent and identifies as queer. He has impeccable craft credentials, having received his Bachelor of Arts in Studio Art and Chinese from Swarthmore College and his Master of Fine Arts in Ceramics from the University of California, Los Angeles. He previously studied at the Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute in Jingdezhen, China. He was awarded a Fulbright grant in affiliation with the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, where he continued his studies in ceramic art. Anderson can boast an artistic lineage that leads from Vivika Heino to Ralph Bracerra and finally to Adrian Saxe, with whom he studied at UCLA. Like Saxe, Anderson has a fully developed sense of irony, adeptly uses symbolism, and employs superb craftsmanship to create what has been called a “pop-baroque” aesthetic. Think gold lusters, exquisite detail, and barely veiled sexual references.

I had admired Alex Anderson’s work from afar until the day when Craft Contemporary curator Holly Jerger and curator of public engagement Andres Payan Estrada announced Anderson’s inclusion in the 2020 Clay Biennial at the museum. This exhibition was entitled The Body, The Object, The Other and featured five sculptures by Anderson. Although this large-scale exhibition was shut down after only two months due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I did get to spend time with Anderson’s work over the weeks it inhabited the space just outside our staff offices. I used my spare moments to study the process and ideas behind the pieces and was impressed with Anderson’s technique and his juxtaposition of ornate beauty, acerbic commentary—often about race—and self-reflection. I was surprised to discover that the work, which had the look and feel of porcelain, was in fact white stoneware, and his use of gilded embellishments reminded me of the opulence and power of European royalty. Anderson worked with the curators to set an almost theatrical stage for his work, and the effect called to mind my secret love of the drama of Italian baroque painting. Meanwhile, his representations of emojis—eggplants, hearts, blackface bombs, and snakes—were anything but formal and polite. Like Caravaggio, Anderson is subversive and seductive. He leans into popular culture while demonstrating a flair for both the dramatic and the precise, with an undertone of bite.

Anderson continues expanding on his favorite themes of millennial culture, self-aggrandizement, and aggressive competition in his new work created specifically for this project. Having selected the artist to make a new work, I wondered what he intended to produce for this project. I called him to get a preview, and he shared some of his thinking. In an email, Anderson wrote, “…the piece will have the appearance of being on fire. The flowers are daffodils, which are part of the narcissus family, and the painting is about escaping from the pain and confines of self-obsession in order to find a higher happiness, as reflected in the facial expression in the gazing pool. It’s about the idea of Narcissus’ reflection escaping the pool and finding freedom as a metaphor of what could lie beyond the millennial culture of narcissism. Things I’ve been thinking about a lot lately! :)”

Frankly, as I return to the museum following 14 months of isolation, escaping the pool of excessive self-reflection is a metaphor I can embrace.

Suzanne Isken is the executive director of Craft Contemporary in Los Angeles, California. A former museum educator, Isken has worked to improve the audience experience for museum goers for nearly 30 years.

Help Make Our Programs Possible as a Member

Join the American Craft Council to receive a subscription to our magazine and help support a range of nonprofit programs that connect and inspire the field.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. To find out more about how National Endowment for the Arts grants impact individuals and communities, visit www.arts.gov.