[Object As...] Leandro Gómez Quintero

[Object As...] Leandro Gómez Quintero

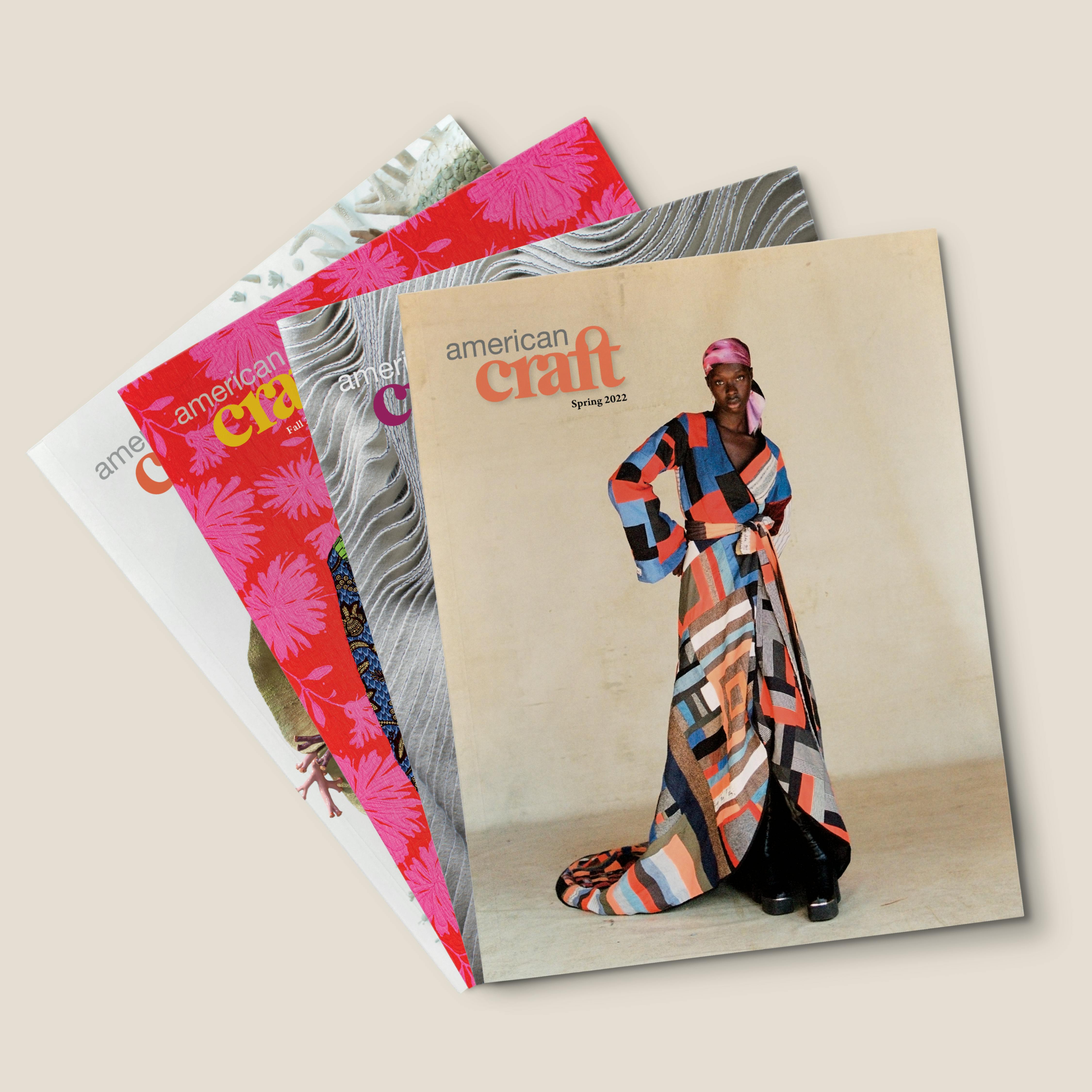

Leandro Gómez Quintero, Transportarte a Baracoa. Photo by Leandro Gómez Quintero.

About "OBJECT AS..."

Objects fashioned by craft artists can do more than appeal to the eye and hand. They can speak to our cultural, political, environmental, and social climates. They can comment on today’s issues and inspire conversations. They can be acts of rebellion.

That’s the point of the “Object As . . .” project, for which six artists were chosen by six curators selected by the American Craft Council. Supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the artists created works that speak—subtly, directly, intimately, publicly—about issues that matter to them. The works testify to the diversity of makers and practices and to the ongoing impact of craft on our lives. Read more about the project.

Below you can listen to an American Craft Podcast interview with one of the participating artists and read their story about how their object came into being and what it means to them, followed by a note from the curator.

Transportarte a Baracoa | Leandro Gómez Quintero

The Willys Jeep, very common in Baracoa, Cuba, is something I have represented many times in my work through my sociocultural project titled Transportarte a Baracoa (transport yourself to Baracoa).

When I started this project, I wanted to reflect the reality that surrounds us here in Cuba. The Willys has been used to carry packages and help with moves. During World War II, it was employed by the military on the Guantánamo naval base, where the strong and brave vehicle proved its value more than once.

The process of building this entirely handmade 1952 Willys Jeep began with deciding on the model, the year, the number of its components, hard top or canvas top, and so on. Materials included poster board, plastic, bottle caps, and Styrofoam—which I carved, shaped, and painted for the tires—and other things to replicate a vehicle seen on the roads here in my province. And I placed a boat on the roof of the Jeep, which could be perceived as something for a fishing trip or for an effort to migrate elsewhere.

The process included paying a lot of attention to the statement the piece was making. I also added some humor and had the comfort of knowing that I was expressing reverence for a classic vehicle.

Within the Willys are the family’s personal belongings, including a life preserver (actually an inner tube). Written on the inner tube, and on the body of the car, are words that reference the Afro-Cuban religions so prevalent here. On the inner tube: Jemanya, the orisha or deity from the Yoruba tradition who is the protector of the waters. The owners of the vehicle undoubtedly added this to protect them as they traverse the ocean in search of what they believe will be a better life.

Leandro Gómez Quintero is an artist living in Baracoa, Guantánamo, Cuba. He studied history and philosophy and taught at the Sede Centro Universitario Municipal Baracoa. He has exhibited at the International Folk Art Market in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and his work was featured in an article by Guy Trebay in the New York Times.

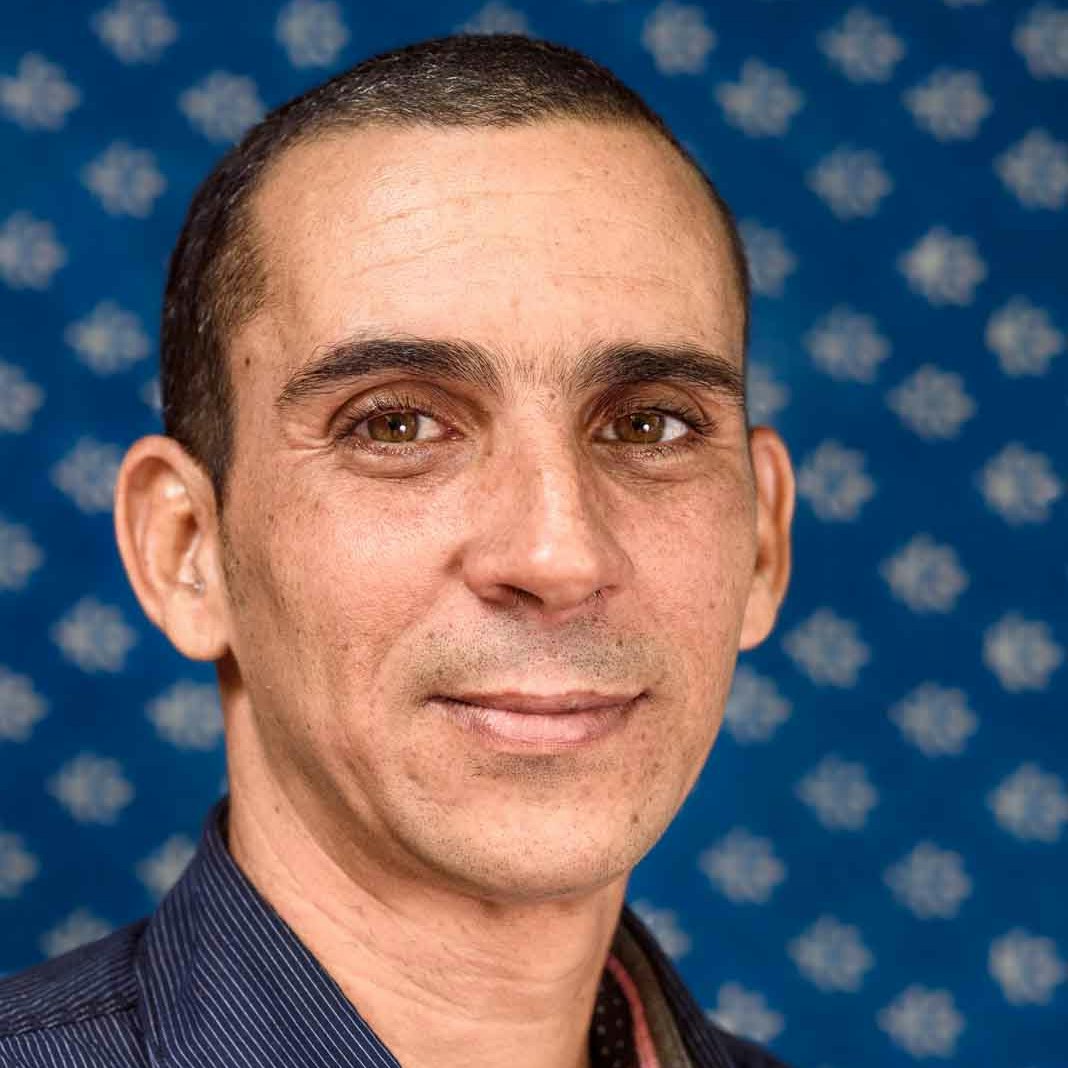

Curator Notes on Transportarte a Baracoa | Stuart A. Ashman

I grew up in Cuba, leaving there at age 12 and returning for the first time in 1997 on a professional research trip when I was director of the Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I have traveled there many times since and have become familiar with many of the artists and craftspeople working on the island.

My wife, Peggy Gaustad, a ceramist, began leading cultural trips to Cuba in 2012. She conducted these four to five times annually and explored the diverse regions of the island. In 2013 she ventured to eastern Cuba, to the town of Baracoa, a small and isolated community on the northeastern tip of the island. It was on that trip that she encountered Leandro’s work. She purchased one of his pieces and brought it back to me as a gift.

I was immediately taken with his inventiveness, his craftsmanship, and his eye for accurate design. I decided that I had to travel to Baracoa and meet him.

The following year, when I was president of the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, California, we organized a trip to eastern Cuba, and I set out to connect with Leandro. I was fascinated by his story. Formerly a high school teacher and university professor, Leandro decided to illustrate his lectures on World War II by making sculptural models of the vehicles that were used in that conflict. He created jeeps, trucks, motorcycles—in short all the motorized machines that were used by both the allied forces and the Third Reich—as a way of interesting students in the subject matter.

Subsequently, his wife, a medical doctor, and others enticed him to begin creating models of the vehicles used in his region. Some of these are, in fact, former World War II vehicles that were adapted as taxis, people transports, and cargo trucks. His creative side blossomed as he modeled the familiar cars, trucks, and buses with an authenticity based on his extensive knowledge of them, and, with artistic license and humor, added elements from his imagination.

His use of everyday materials, including found objects and recycled products, is additional testimony to his creative spirit: a drinking straw becomes an exhaust system; lids of toothpaste tubes become hubcaps; packing Styrofoam is carved and painted to become a variety of tires, and discarded vinyl becomes the roof of a vintage Willys Jeep.

His reverence for accuracy in his creations is obvious and clearly points to his commitment to history. He can easily identify the originals of his model vehicles, no matter how whimsically he may have altered them. If you ask him about a particular one, he will say “Oh, you mean the ’42 Willys?” or the “’43 Dodge Power Wagon?”

In the piece he created for this project, Transportarte a Baracoa, he makes a strong social and political commentary on the issue of Cubans migrating to Florida. It’s a vintage Willys Jeep packed with a family’s belongings. Mounted on the roof is a homemade barge and included in the vehicle is an inner tube in case the barge fails. On the inner tube is the word protegenos (protect us) and the name “Jemanya,” the ruler of the oceans and the other waters in the Afro-Cuban religion. This deity (also known as Yemayá) is invoked for the protection of travelers.

One inscription on the barge is “La Virgen”—for the Virgin Mary, who, as Our Lady of Charity, is the patron saint of the island. Legend has it that three fishermen were shipwrecked in a storm, and she rescued them. Finally, the barge invokes “Orula,” the saint of divinations and a symbol of hope for a brighter future.

I asked Leandro to photograph the piece near the ocean, which is just across the street from his house. While he set the model up, people came out, intrigued and a bit suspicious of what he was representing. When they challenged him, he simply responded, “Oh, they’re just going fishing.”

For Leandro Gómez Quintero, what began as an instructional aid in his history classes has evolved to the point of being recognized by New York Times art writer Guy Trebay. “Some call it craft,” Trebay writes. “I call it art.” Leandro was also selected numerous times to participate in the International Folk Art Market in Santa Fe, and now comes this recognition by the American Craft Council.

Stuart Ashman is a cultural ambassador who has worked in the arts in New Mexico and internationally for over 35 years. He was raised in Matanzas and Havana, Cuba, before his family relocated to New York where he attended the City University of New York receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree in Photography and Fine Art. His additional studies include graduate work at the Rochester Institute of Technology and personal interactions on his photography with Minor White and Paul Caponigro. He was also selected to participate in the Getty’s Museum Leadership Institute.

He recently launched Artes de Cuba, a gallery of contemporary art and craft from Cuba. Previously, he served as the chief executive officer of the International Folk Art Alliance and as the executive director and chief curator of the Center for Contemporary Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. His experience includes postings as president and CEO of the Museum of Latin American Art; director of the New Mexico Museum of Art; executive director of the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art; and an appointment by the governor as cabinet secretary of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs where he served for two gubernatorial terms. He also served as expert consultant for the United States Peace Corps and expert speaker for the US State Department. He serves as vice-chair of the Richardson Center for Global Engagement, the Board of Directors of Paul Allen’s Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum, and the Santa Fe County Lodger’s Tax Advisory Board.

He has published numerous articles and exhibition catalogs and co-authored Photography New Mexico in 2009, Abstract Art in 2003, and Harlistas Cubanos in 2006.

Help Make Our Programs Possible as a Member

Join the American Craft Council to receive a subscription to our magazine and help support a range of nonprofit programs that connect and inspire the field.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. To find out more about how National Endowment for the Arts grants impact individuals and communities, visit www.arts.gov.