[Object As...] Bukola Koiki

[Object As...] Bukola Koiki

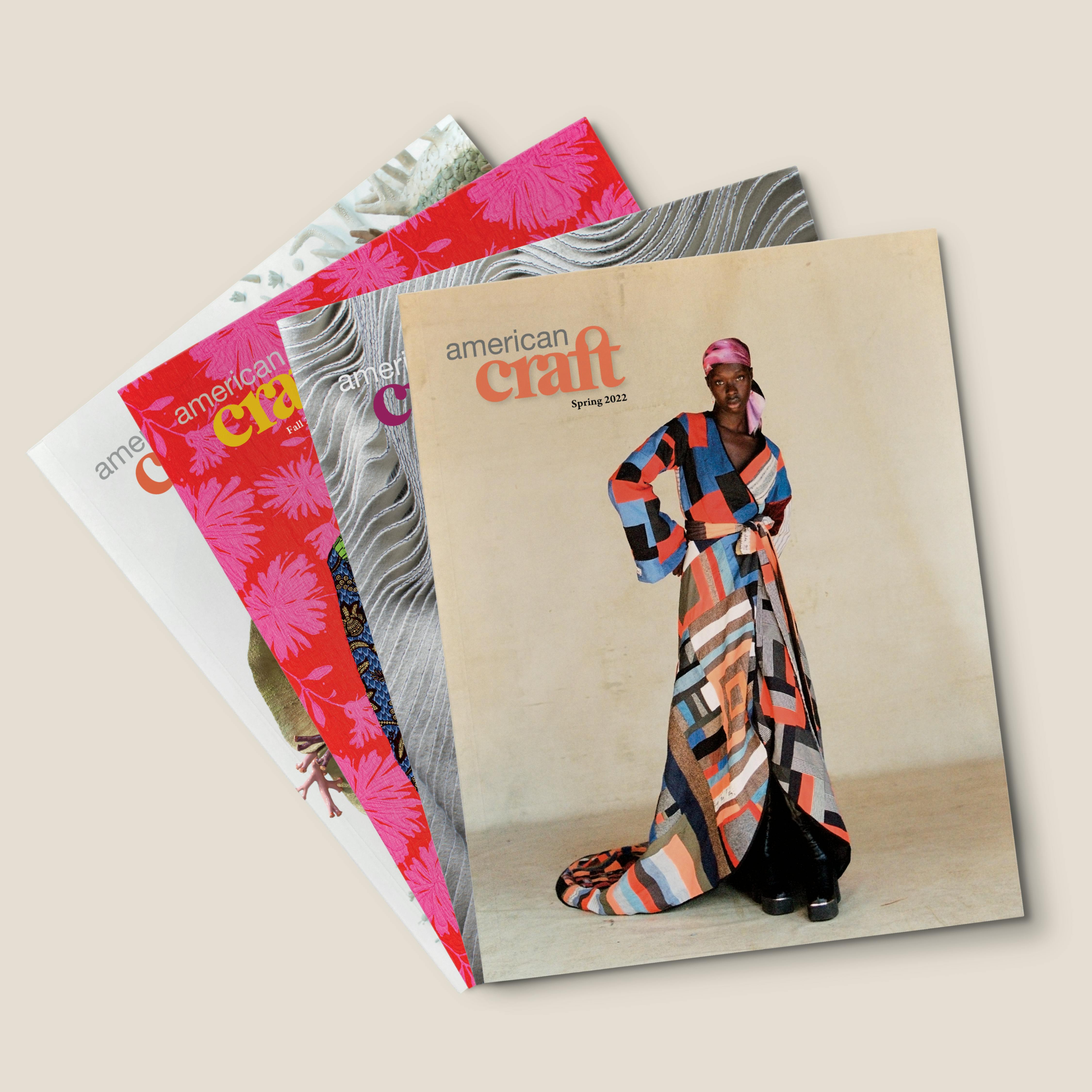

Bukola Koiki, The Pull. Photo courtesy of the artist.

About "OBJECT AS..."

Objects fashioned by craft artists can do more than appeal to the eye and hand. They can speak to our cultural, political, environmental, and social climates. They can comment on today’s issues and inspire conversations. They can be acts of rebellion.

That’s the point of the “Object As . . .” project, for which six artists were chosen by six curators selected by the American Craft Council. Supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the artists created works that speak—subtly, directly, intimately, publicly—about issues that matter to them. The works testify to the diversity of makers and practices and to the ongoing impact of craft on our lives. Read more about the project.

Below you can listen to an American Craft Podcast interview with one of the participating artists and read their story about how their object came into being and what it means to them, followed by a note from the curator.

The Pull | Bukola Koiki

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the in-between spaces of immigrant life were made more acute for me than ever. Searching for the feeling of home during the seemingly endless isolation of that time, I found comfort in abstracted forms and shapes of houses. I made The Pull in response to my yearning for Nigeria and beloved family members.

The Pull is two conjoined house-objects created from stiff synthetic fabric traditionally worn as elaborate geles (head ties) during special family occasions in Nigeria. Geles are not of Nigerian origin but were created in the UK in the 20th century and embraced by West Africans as part of traditional wear. Chinese factories are now replicating the textile. This provenance makes them, like me, liminal, transnational entities.

I’ve used them to create origami folded-house forms that represent the complexity of my experience of being a Nigerian-born American immigrant. The black house represents the African continent and the red one, the American continent. I painted the red house form in red ochre natural pigment, the color of the red soil found in territories of my people, the Yoruba ethnic group of western Nigeria. Black ink marks the ochre surface for the roads to my first dwelling in each city I have lived in since moving to the United States. Next, I split a significant quote from author bell hooks in half and hand-embroidered it in my handwriting on each roof. Circling the objects allows the viewer to read the full quote for complete understanding. Finally, an umbilical cord of 24 embroidery strands connects the forms—one for each year I have been away from the country of my birth.

This work is my immigrant longing given form, and a love letter to those who navigate the spaces between nations, borders, and languages.

Bukola Koiki is a Nigerian American transdisciplinary artist known for material and technical research in her practice. She received an MFA in applied craft and design in 2015 from the Pacific Northwest College of Art. She lives in Lewiston, Maine.

Curator Notes on The Pull | Malene Barnett

What is home? Is it a place or a feeling or something else? As a child of the African diaspora in America and daughter to Caribbean immigrants, I find that I’m engaged in a constant personal search for the meaning behind the word. Trying to feel as though you belong in lands you are not akin to is like piecing together fragments of history. It is a continuous reinvention, and it can be exhausting. So I find comfort by seeking out objects crafted by hand. I come from a lineage of makers: my grandmother was a gifted fashion designer, and as a child I watched my mother turn jute yarn into intricate macramé wall hangings. These women’s lives set the stage for my appreciation for archival materials, craftsmanship, objects, and the collective memory held within each. Handcrafted pieces spark memories of the past and offer proof that home is more than a place.

I often gravitate toward textiles, searching for symbols and objects to reconnect with my heritage. I'm particularly interested in artists who utilize West African textile traditions and challenge western norms in their work. A few years back, during my search for graduate school programs, I discovered Nigerian-born textile artist Bukola Koiki's work and was immediately drawn to it. I admired her detailed research, textile-making process, embroidery skills, and activism. We got in touch through Instagram, and despite the limitations involved in that connection, I felt a kinship. Her celebration of Yoruba culture is closely allied with my desire to connect to my Nigerian ancestry and with Nigerian craft traditions.

Bukola's object, The Pull, echoes a sentiment many people in the diaspora experience and identify with, that feeling of always searching for a home and a space of belonging.

The Pull is two houses made from a stiff, synthetic textile used to make geles, traditional Nigerian head ties. The houses represent the complexity of Bukola's American immigrant experience, color-coded to embody the two continents she straddles, Africa and North America. She utilizes natural-pigment paint of black for one and red ochre for the other. The latter symbolizes the soil in the lands of her people, the Yoruba ethnic group of western Nigeria. Black ink marks on the red house-form map out the streets near her first residence in each American city she's lived in. A cord made from 24 embroidery strands connects the two structures, with each strand representing a year Koiki has been away from the country of her birth. Quotes by the late bell hooks exploring the nature of home are hand-embroidered on the roofs of the structures, inviting viewers to consider what this powerful concept means to them.

The Pull also reflects on the textile traditions of Bukola's home country and the paradoxical story of the material used to make geles. The material was non-native; made in the UK, it was brought to West Africa and assimilated into Nigerian customs—a diasporic experience in reverse. Nevertheless, in the 1990s the gele became an iconic symbol for African Americans, who wore it to show their African pride. Worn by mothers, aunts, sisters, and daughters, geles represent beauty, pride, and regality for me, a tradition from the past that is also very much present.

I can visualize my great-great-grandmother selecting the best fabrics for her geles. I can imagine selecting materials from a local textile maker and ordering custom-made outfits to coordinate with the gele for special celebrations. As an artist and activist, I work to instill pride in Black cultural traditions as seen through the lens of a maker. This work resonates with me because it reveals, through craftsmanship, that our bond to our ancestors was not broken during the diasporic movement of peoples. It symbolizes pride and beauty, an opportunity to reconnect with the past and embrace and take ownership of the present. It grounds us in our heritage and it shows me a way to find my way home.

Malene Barnett is a multidisciplinary artist and textile designer based in Brooklyn. As an activist, she envisions a modern black experience rooted in the cultural traditions and practices of art in the African diaspora.

Help Make Our Programs Possible as a Member

Join the American Craft Council to receive a subscription to our magazine and help support a range of nonprofit programs that connect and inspire the field.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. To find out more about how National Endowment for the Arts grants impact individuals and communities, visit www.arts.gov.