[Object As...] James Maurelle

[Object As...] James Maurelle

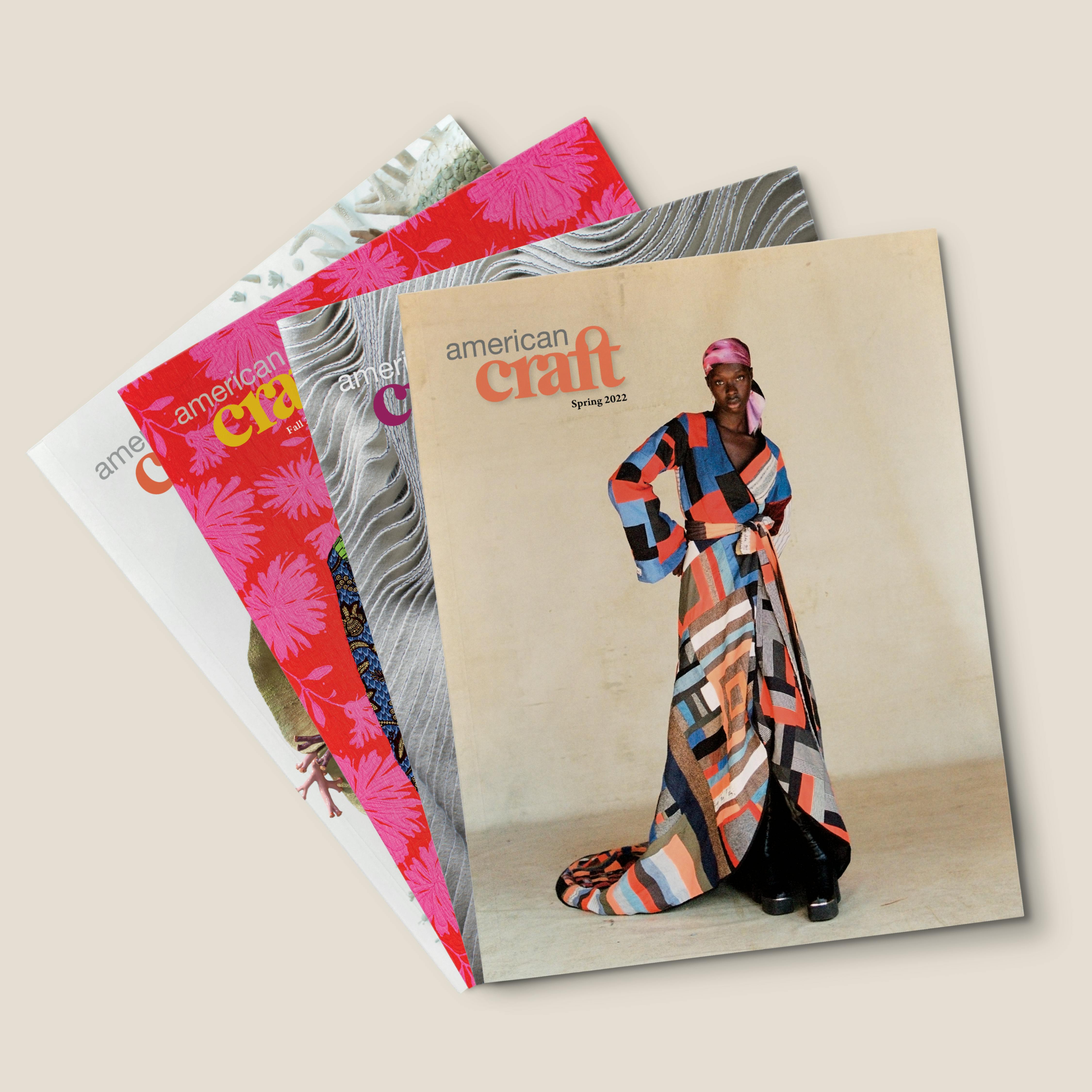

James Maurelle, MAROON(ED). Photo by Karen Mauch.

About "OBJECT AS..."

Objects fashioned by craft artists can do more than appeal to the eye and hand. They can speak to our cultural, political, environmental, and social climates. They can comment on today’s issues and inspire conversations. They can be acts of rebellion.

That’s the point of the “Object As . . .” project, for which six artists were chosen by six curators selected by the American Craft Council. Supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the artists created works that speak—subtly, directly, intimately, publicly—about issues that matter to them. The works testify to the diversity of makers and practices and to the ongoing impact of craft on our lives. Read more about the project.

Below you can listen to an American Craft Podcast interview with one of the participating artists and read their story about how their object came into being and what it means to them, followed by a note from the curator.

MAROON(ED) | James Maurelle

The word maroon refers to a location and a culture I hold dear in my childhood imagination. It’s a complex, mixed, creolized concept that’s very important to me as a color and an identity.

It became a vision of speed, strength, endurance, and fortitude as I watched the Maroons, a West Indian cricket team, on television with my father. Dancing bodies hovering over a sea of green, all wrapped in white linen and topped with maroon caps, held my fascinated gaze. This memory entered my mind in the creation of the artwork MAROON(ED), which could be a cricket bat, a paddle for a boat, or something else about memory and escape.

How do you capture an era while expressing agency, freedom, grace, and the residue of a colonialist past? Language was my entry point. Maroon, the Maroons, and marooned flowed together in my mind—that iconic cricketing color, bands of formerly enslaved people who escaped to the Jamaican mountains, and the idea of being a castaway.

What are the tools you need to free yourself?

I toiled with the notion of creating a tool that embodies sport, escapism, and self-defense; that expresses movement and stillness, a call and response between sporting leisure and creative labor.

I call this function the in-between.

How do you escape and assert agency marooned on an island?

I wanted to fashion a tool that is multifunctional and dysfunctional at the same time.

These are some of the concepts I addressed head-on, and this is the tool I constructed to escape my captor, whether that captor is time, location, the elements, or Being itself.

Sculpture, video, photography, and recycled materials are James Maurelle’s physical and digital primes. His work, which investigates the correlation between labor and creativity, has been shown in New York, Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Austin, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Richmond, Cincinnati, and San Francisco.

Curator Notes on MAROON(ED) | Jennifer-Navva Milliken

James Maurelle has built a long and multivalent career as an artist and teacher. All of the components of his arts trajectory—musician, film editor, international DJ, sculpture artist, thinker, and poet—are deeply ingrained in his body of work. They inform the shape and treatment of an inchoate idea. His work is never about one solitary concept—instead, a single object will speak to memory and nostalgia; history and society; gratification and pain; injustice and dignity.

All of these elements bring a vibrating awareness to James’s work, enfolding identity, environment, strength, and humility. He is not afraid to leave the surface of a piece of wood coarse and abrasive when roughness is called for, or to sand it to a high shine when he needs a smooth curve for the eye to glide over. Labor is a conceptual component in this work—it disciplines the creative impulse and intensifies the seductive power of the object. Materials are salvaged, rescued from urban neglect, and habilitated until they assert themselves to the artist. Sustainability and economy are parts of this practice, but more urgent is the ennoblement of the street as the source of precious materials. Marble fragments, decapitated furniture, and architectural castoffs are artifacts of an optimistic but hopelessly flawed society. In James’s studio, these materials receive space for circulation and renewal.

MAROON(ED) operates on all of these frequencies, and more: inspired by the story of the improbably victorious West Indies cricket team, it’s also a proxy for the audacious act of overcoming colonialism and oppression through diligence and determination. The “Windies” prevailed in a system whose rules were written to keep them down. Through study and perseverance, these Black athletes from 15 Caribbean countries—resplendent in their maroon-colored caps—triumphed over white teams in the UK, shaking off stigmas and mockery and writing, in the words of legendary batsman Viv Richards, “…the history that you never forget.” 1

Craft, like athletics, is a sociopolitical endeavor. A generative act performed by the skilled body and creative mind, it links the one to many—generations of makers, collaborators, and consumers, who form an economy. One can delight in MAROON(ED)’s humanely scaled proportions, the invitation to take hold of the handle, to feel its raw texture and swing against the weight while considering what might be smacked by these fine but punitive bristles. These actions also suggest a “call and response”—a descriptor James often brings into his work—between object and user. Mind and body work in sync to connect to a community of users through rhythms and signs.

Woodcraft demands skill, patience, understanding, and humility. Wood has warmth and tactility. It was alive, but even in death it is in flux. From the first figurative depiction, the first fertility amulet, wood has been a stand-in for the human body. Its pliability and cellular materialism parallels our own fragile, mysterious, and resistant bodies. Research informs us that trees live in societies and thrive through complicated networks, establishing alliances, orchestrating takeovers, nurturing each other, and signaling distress. Though the intricacies and processes that govern the systems of the forest are beyond human comprehension at present, the values they represent to us—the importance of collaboration, support, and sense of place—are also represented in craftsmanship.

1. Viv Richards, quoted in the documentary film Fire in Babylon (2010), directed by Stevan Riley, Cowboy Films/Passion Pictures.

Jennifer-Navva Milliken is the executive director and chief curator for the Center for Art in Wood. Prior to her arrival at the Center, she served as an embedded staff member in international art museums, as an independent curator, and as the founder of a cross-disciplinary art space. Her exhibitions have been presented in museums, art fairs, galleries, and unconventional spaces, and her writings have been included in exhibition catalogs, anthologies, and publications that investigate and critique the intersecting fields of art, craft, and design. With a global perspective, honed through a life split between two continents, she is driven by the extraordinary power of the arts to challenge preconceptions and bridge divides.

Help Make Our Programs Possible as a Member

Join the American Craft Council to receive a subscription to our magazine and help support a range of nonprofit programs that connect and inspire the field.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. To find out more about how National Endowment for the Arts grants impact individuals and communities, visit www.arts.gov.