[Object As...] Morel Doucet

[Object As...] Morel Doucet

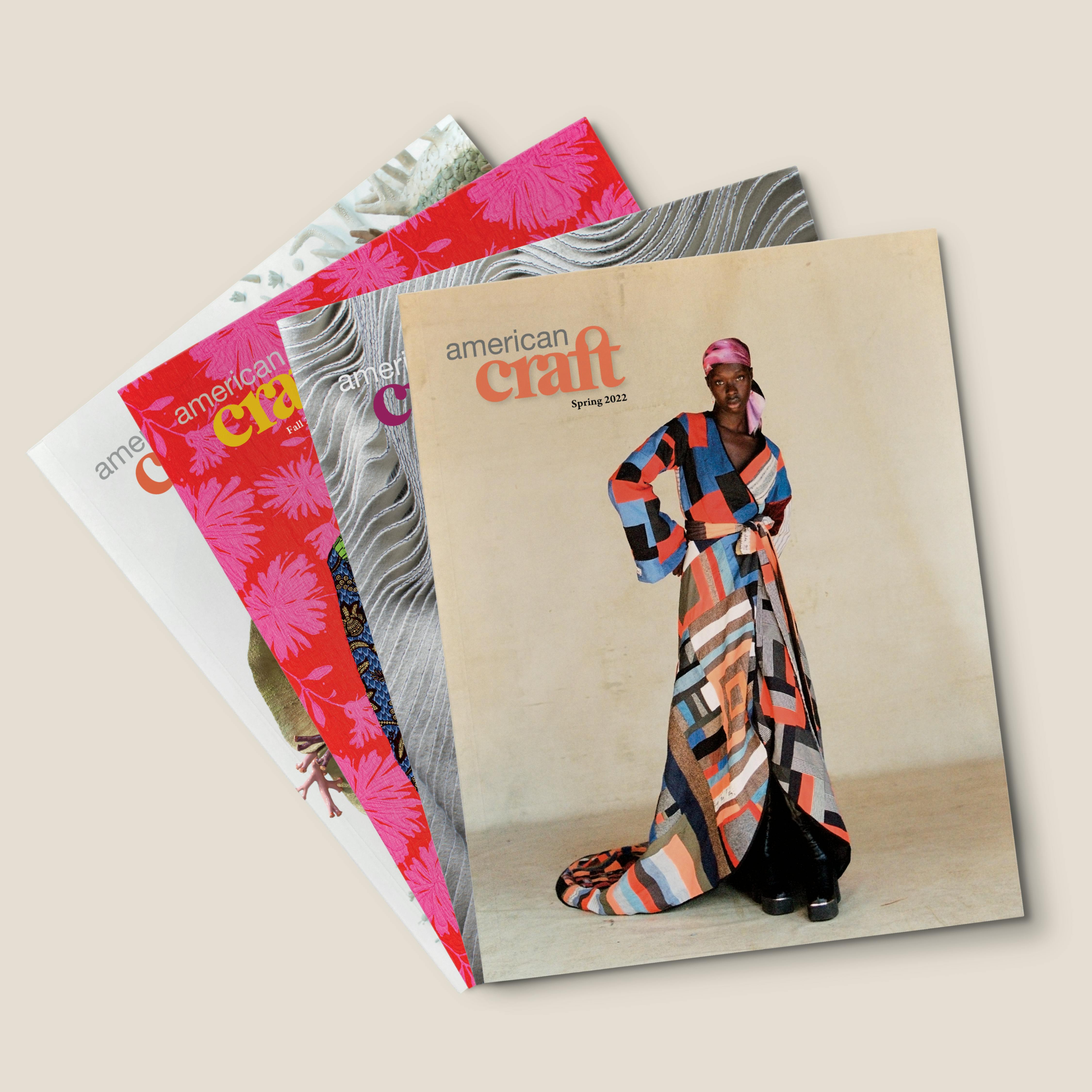

Morel Doucet, The Hills We Die On (Flowers for President Jovenel Moïse). Photo by Pedro Wazzan.

About "OBJECT AS..."

Objects fashioned by craft artists can do more than appeal to the eye and hand. They can speak to our cultural, political, environmental, and social climates. They can comment on today’s issues and inspire conversations. They can be acts of rebellion.

That’s the point of the “Object As . . .” project, for which six artists were chosen by six curators selected by the American Craft Council. Supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the artists created works that speak—subtly, directly, intimately, publicly—about issues that matter to them. The works testify to the diversity of makers and practices and to the ongoing impact of craft on our lives. Read more about the project.

Below you can listen to an American Craft Podcast interview with one of the participating artists and read their story about how their object came into being and what it means to them, followed by a note from the curator.

The Hills We Die On (Flowers for President Jovenel Moïse) | Morel Doucet

My grandfather, age 87, has farmed in Haiti for the past 55 years. Working the land, he put all 11 of his children through school.

When I was a child, I loved to spend time with him. In the middle of the day, when the heat became unbearable and the animals were seeking shelter in the foliage, he and I would head toward the river to cool off. We would talk about life, my aspirations, and school. Our conversations would always end with him telling me that if you know where you come from, you have a vision of where you’re going; nobody can change your conviction or purpose.

Once the day ended, my Nana would greet my grandfather with a hot cup of coffee in a porcelain cup. My grandparents’ china always stood out to me; it was the starkest white presence in the whole pantry. The outer rim of the coffee cup was embellished with butterflies and plants. The entire china set was brought out only on special occasions, including presidential elections.

In fashioning my object, I wanted to pay homage to Haitian President Jovenel Moïse, assassinated in July 2021. He came from humble beginnings; he often recounted how he had grown up on a large sugar plantation in a rural area of the country and could relate to the vast majority of Haitians, who live off the land.

The Hills We Die On (Flowers for President Jovenel Moïse) commemorates Mr. Moïse’s legacy and his vision for the Haitian people—a vision that has been left in fragments. The butterflies that grace the face are symbols of transformation and hope. The stark white porcelain head also pays homage to the cup of coffee my grandfather would peacefully drink after his day’s work on the farm.

Morel Doucet is a Miami-based multidisciplinary artist and arts educator who hails from Haiti. He employs ceramics, illustrations, and prints to examine the realities of climate gentrification, migration, and displacement within the Black diaspora communities.

Curator Notes on The Hills We Die On (Flowers for President Moïse) | Sanjit Sethi

Morel Doucet’s The Hills We Die On (Flowers for President Moïse) is an object that fills me with questions which led me to write the below letter to the artist.

February 10, 2022

Dear Morel,

It has been three years since I visited your studio in Miami, and I hope you are well and have remained healthy and strong over these turbulent months. The object that you produced for ACC’s Object As… project, The Hills We Die On (Flowers for President Moïse), fills me with many questions about process, place, and resonance. I hope you indulge me by listening to some of them in this letter.

How many flowers were left on your studio table that never made it onto The Hills We Die On? How many butterflies? Did the lone dragonfly that is separate from the vessel escape being slipped and scored onto the object? Or does it show a direction forward? Or protect the face from further harm? What tools made the small vertical dotted lines that run up and down the object's neck? They remind me of the ritual scarification lines that appear on ancient Yoruba shrine heads. Is the press-molded seam line that connects both halves of the head more about the functionality of joining or a way of showing, symbolically, two distinct and separate halves?

I have questions about the edges of the rim of the vessel: Was the porcelain leather-hard or more brittle? How would you describe this process? Tearing? Breaking? Ripping? How did you know when to stop? Did you use a tool like pliers or your fingers? Were you skirting between the boundaries of intentionality and responding to the characteristics of the porcelain?

What is the story behind the head? Did you make this press mold yourself or find it in some obscure ceramic supply store or antique warehouse? With its Buddha-like downcast gaze, is it supposed to inspire contemplation and soul-searching or represent a type of burial shroud or death mask? Are we encountering this figure at the end of its life, in a moment ultimately of stillness, a kind of parinirvana? In showing this work to my 8-year-old daughter, she remarked on the smooth, hairless quality of the face, void of eyebrows and lashes. She asked, “Did he model this after someone he knows? And were the slits of the eyelids drawn with a tool or his fingernail?” Does the head emulate the physiognomy of President Moise? I also wonder about the round shape of the base: Does it rock back and forth? Does it need to be steadied?

I noticed you have not used glaze to obscure the bisqueware-like quality and pinkish hue of the clay body; how does this relate to the porcelain in your childhood memories? Is the head upside-down or are we? Your vessel comes with two titles; does one title exist without the other? Do we take the two titles in one breath? Or does each require its own space for contemplation?

I hope these questions generate more conversations the next time I am fortunate enough to sit again in your studio space and chat with you. In the meantime, be well.

My best,

Sanjit

Sanjit Sethi is an artist, curator, cultural leader, and the 19th president of the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. Sethi’s previous positions include director of the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design at George Washington University; director of the Center for Art and Public Life at the California College of the Arts; and executive director of the Santa Fe Art Institute.

Help Make Our Programs Possible as a Member

Join the American Craft Council to receive a subscription to our magazine and help support a range of nonprofit programs that connect and inspire the field.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. To find out more about how National Endowment for the Arts grants impact individuals and communities, visit www.arts.gov.